When in late spring of 1624 Dutch families returned to settle on the islands at the mouth of the Hudson – Governors Island is one of the plausible first – to move in and consolidate a colonial settlement that would remain in their hands just 40 years before falling into English hands, the story of New York – New Amsterdam in origin – began, and over the next 400 years would charge that complex archipelago on the Atlantic coast with all the meanings that still make it a symbol today, the cultural capital of the world in some seasons, a reference for urban form in others. The idea of laying out an orthogonal grid to give a measure to such complexity came with the early-19th-century Commissioners Plan, and for a century and a half the idea of developing in height seemed to coincide with the very identity of New York's core. Skyscrapers, brownstones and projects more or less regularly line endless axes within rectangular lots, as rectangular is the rational landscape void of Central Park.

With 1959 a new symbol arrived, to join the team of the various Chryslers, Empire States and Rockefellers, but this time it would not line up: the tower conceived by Richard Roth (of Emery Roth and Sons), joined by Walter Gropius and Pietro Belluschi, announced itself as the crowning glory of Grand Central Terminal, and a consequent perspective closure to Park Avenue. It was to be the object of fiery contestation and controversy, but also the symbol of a post-war Midtown Manhattan that, together with the less cumbersome Time-Life Building, accompanied New York through one of the most glorious and at the same time complex periods of its history as a cultural symbol. Domus announced the arrival of the Pan Am building – today the MetLife building – in September 1959, on number 358.

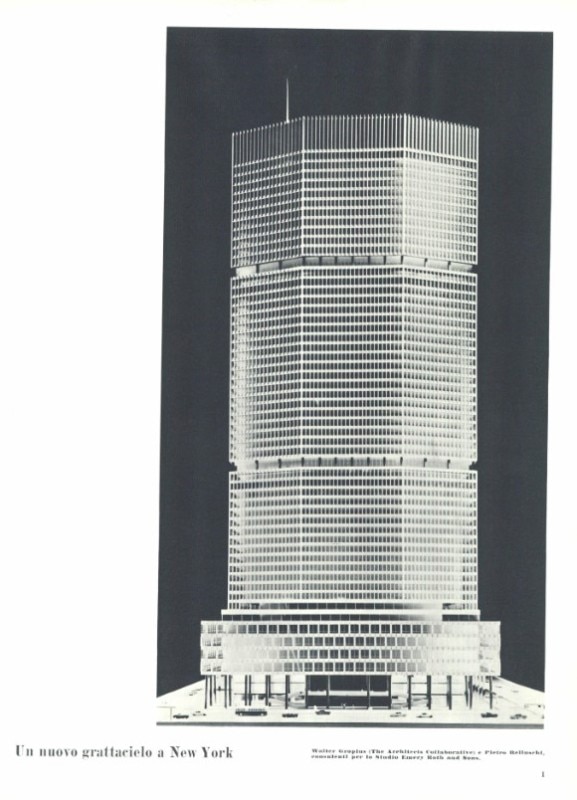

A new skyscraper in New York City

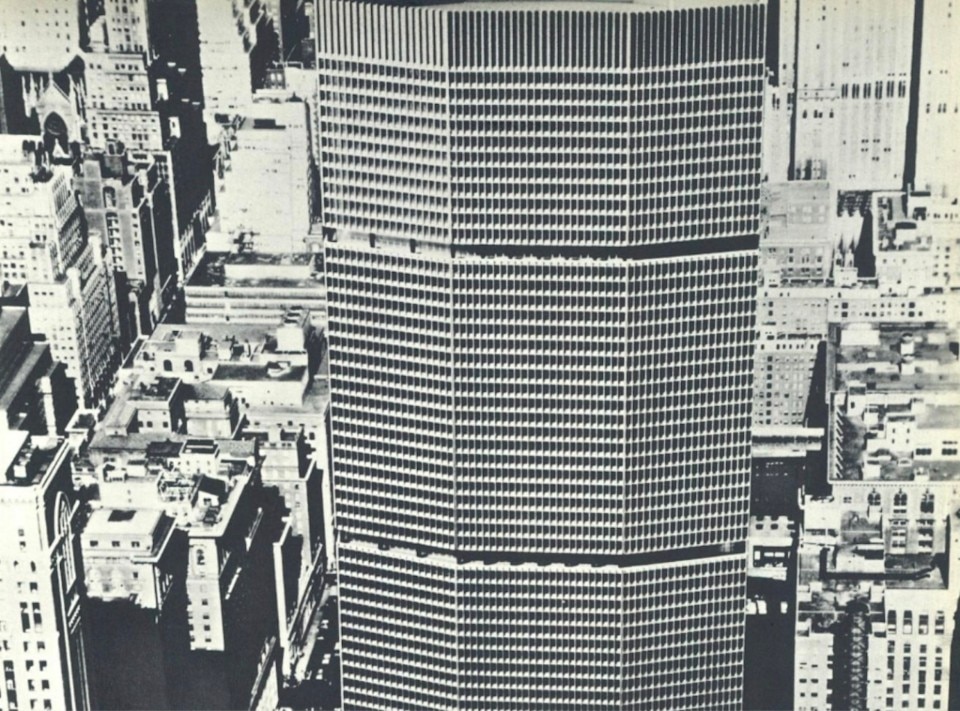

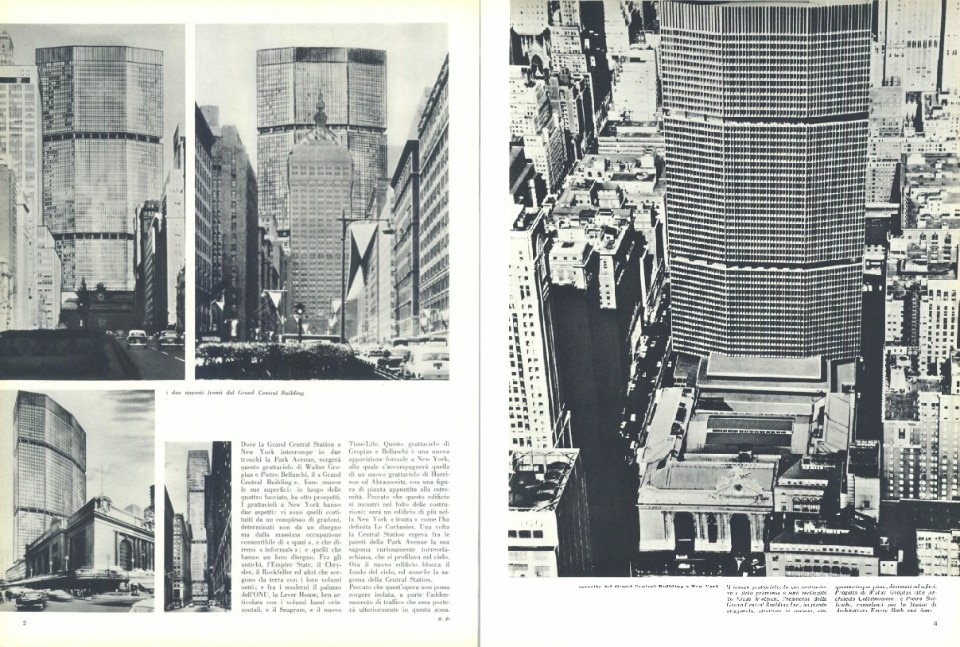

Where Grand Central Station in New York City cuts Park Avenue in two, the skyscraper designed by Walter Gropius and Pietro Belluschi, the “Grand Central Building”, will rise. It moves its surfaces: instead of four facades, it has eight elevations.

Skyscrapers in New York have two aspects: there are those that consist of a complex of steps, not determined by a design but by the maximum allowable occupation of “spaces”, and which we will call “informais”; and those that have a design of their own. The old ones include the Empire State, the Chrysler, the Rockefeller, and others that rise from the ground with their clear volumes; and the modern ones include the UN building, the Lever House, well articulated with low horizontal volumes, and the Seagram and the new Time-Life.

This skyscraper by Gropius and Belluschi is a new formal appearance in New York, which will be accompanied by that of a new skyscraper by Harrison and Abramovitz, with a figure of pointed plan at the end. Too bad that this building will get stuck in the middle of the construction; it will be one more building in the “hirsute” New York, as Le Corbusier called it.

Once, Central Station stood between the walls of Park Avenue, its strangely Torrevelasque silhouette rising into the sky. Now the new building blocks the bottom of the sky and absorbs the silhouette of Central Station. It is a pity that this work cannot stand alone, except for the traffic it will bring to the area.