Indelibly linked to the sea blue of the ceramics surrounding guests from the very moment they enter, the Hotel Parco dei Principi holds a highly prestigious position within the galaxy of Ponti mythology because, in addition to embodying the image of modern Mediterranean tourism, it also embodies many of the signature principles of its designer: it was born not out of nothing (out of the blue, to be precise), but out of the sensitive reinterpretation of an existing story – the eighteenth-century hillock belonging to the Count of SIracusa and then to the Cortchacow – so Ponti would privilege the interior over the exterior shape of the building, giving full expression to his quest for an innovative dialogue between the modern and the decorative, and also collaborating with figures such as Ico Parisi and Fausto Melotti (whom we see returning in various projects, such as the Casa di Fantasia in Milan).

As it was remarked upon its 50th anniversary, Parco dei Principi anticipated the concept itself of design hotels, as a work of art – a collective one, in a way – expressed inside an interior, among majolica, white and blue pebbles, and tiles for which Ponti takes care of the production and the conception: “I always think about these infinite possibilities of art: just give someone a square, 20 by 20, and even though over the centuries just about everyone has gone wild with infinite designs, there is always room for a new one, for your one. A very witty friend asked me what would happen after the last designer made the last design, when all designs were done. Nothing, because there will never be a final design, and there will never be a final designer”. These are words by Ponti that Fabrizio Mautone recalled in 2017 on the occasion of the exhibition dedicated by Triennale Milano to these ceramics.

We report here instead the other words with which Ponti portrayed the project, making it literally disappear within a harmonious painting of landscape, colors and atmospheres: it was June 1964, on Domus 415.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

Blue skies, blue sea, blue islands, blue tiles, green trees, green waters, roses thrown to a princess, a dancer

It’s not a song – “blue sky” or “blue sea” or “azulejos azules” – as much as Sorrento is the subject of songs. And it’s not a fairy tale, even though a great Neapolitan painter of the 19th century, Palizzi, gallantly painted rose petals at the feet of Princess Korciacov, in bed; and although on the marble terrace of the 19th century pavilion, in this park, there is still the tiny imprint of the foot of the famous Sedova, dancer at the Russian court.

It’s a story that becomes a legend. There was the park of the Villa Korciacov, where lived the beautiful Korciacov, the princess still remembered by the people of Sorrento for the splendor of her parties and for her generosity in giving to the poor, even when she declined, and for the famous long cigarette holders and for her extraordinary love for plants. Plants and flowers of the park – maintained by ten gardeners – around the villa and the pavilion she began to build, dreaming of receiving the Imperial Family of Russia – and which remained unfinished, a ruined relic among the plants of the park. Here, a man with the genius to discover the qualities of what everyone knows and no one notices, was able to have a hotel built in the park.

He took an architect there on a day when everything was blue due to the fog of intense heat: blue sky, blue sea, distant blue profiles on the horizon of Capri, Ischia, Procida (blue islands), Posillipo (blue peninsula) and on land, Vesuvius (blue volcano). The architect said: “Let the architecture be blue and white on the outside and white and blue on the inside.” The architecture did not succeed in being faithful to the design in its structures and finishes, but where nature helped, things went reasonably well: the terrestrial green path through the park, among solemn trees; the aquatic green pool, conceived not as a basin for sports swimmers but as a water mirror for forest nymphs, from which short islands emerge for classical poses, in the style of Récamier or Paolina, of feminine beauty; and from the water emerges a concrete staircase to be climbed and then plunged into.

The rest of the designed things – fabrics, walls, floors, glasses, tablecloths – are (or should be: the architect was no longer there) white and sky blue, like the sky, the shadows, the distances and the sea.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

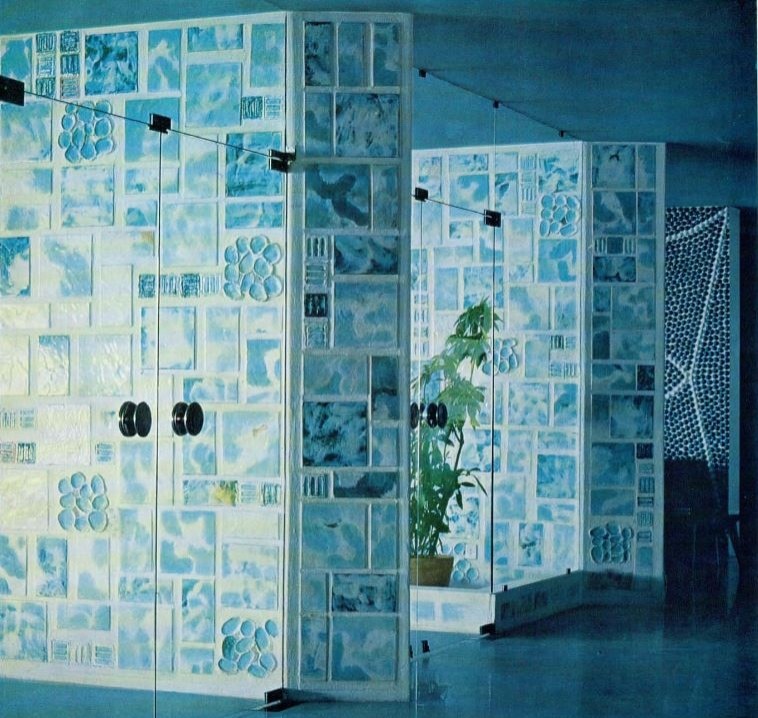

It was the maiolica, the architect’s passion, that came to his rescue: in the floors, with the Salerno tiles by D’Agostino, which resulted in a hundred different new floors with thirty new designs, composed in various ways, as many as the rooms (the architect’s passion for creating these happy works); and in the walls of the rooms, with the Melotti ceramic slabs, white and blue, cloudy, walled, to cover the pillars, as you can see, and where every intrusive volume loses its consistency because of the reflections. Among the designs of the new tiles, offered for perfect execution by the Salerno skill of the D’Agostino family, there are moons (honeymoon) and natural geometries. And on the stairs, at the entrance and outside, the architect used another of his ideas, that of the ceramic pebble mosaic, realized by Ceramica Joo. He says it has a beautiful effect and you will see. The ceilings, headboards and doors are blue, the rest is white. And the architect taught how to make blue methylene spaghetti (and chickens), healthy and wonderful; and he chose bowls and trays made of a stunning material, white on the inside, blue on the outside. In vain.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

From the hotel, which is built on a high ancient tuff wall, you descend – through galleries in the rock and caves – to the sea, where you are greeted by a crescent-shaped pier, here a beached crescent. Some of these galleries and caves have remained intact, but it seems that Salvatore Fiume covered some of them with lime, painting deities inclined to natural, elemental and healthy loves, those loves that have branched out into the genealogical trees of mythology.

Is all this true? It was true in the architect's mind; it is not true in reality (except for the white and the blue). That’s how he works, works, works, and can't express himself.

.png.foto.rmedium.png)