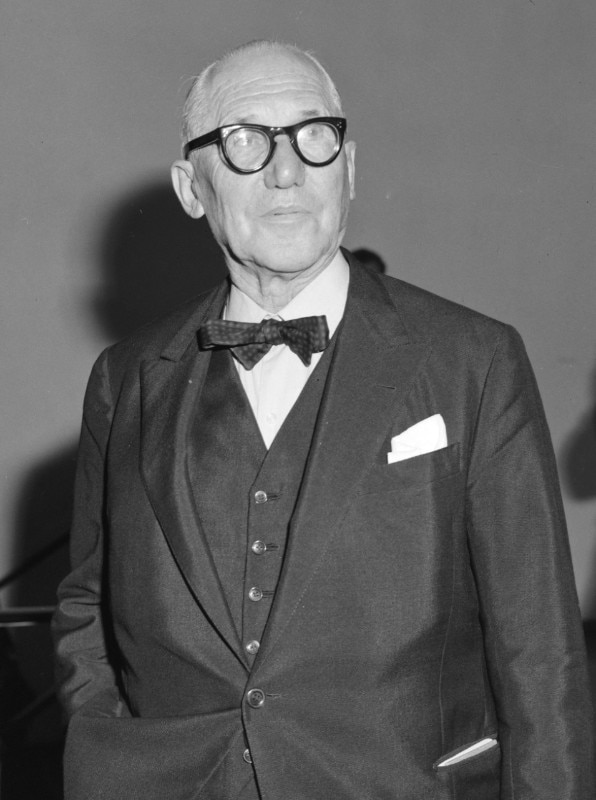

Aldo Rossi wrote that every great man accomplishes something important in his 30s. Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris accomplished more than just a simple something at that age: he could boast formative experiences in the studios of Auguste Perret and Peter Behrens, a Bildungsroman published posthumously like Voyage d’Orient, a model district in Bordeaux (Cité Frugès in Pessac), and above all a memorable magazine such as the L’Esprit Nouveau, which was published in 28 volumes between 1920 and 1925, each one of them graphically marked by a large colored number on the cover.

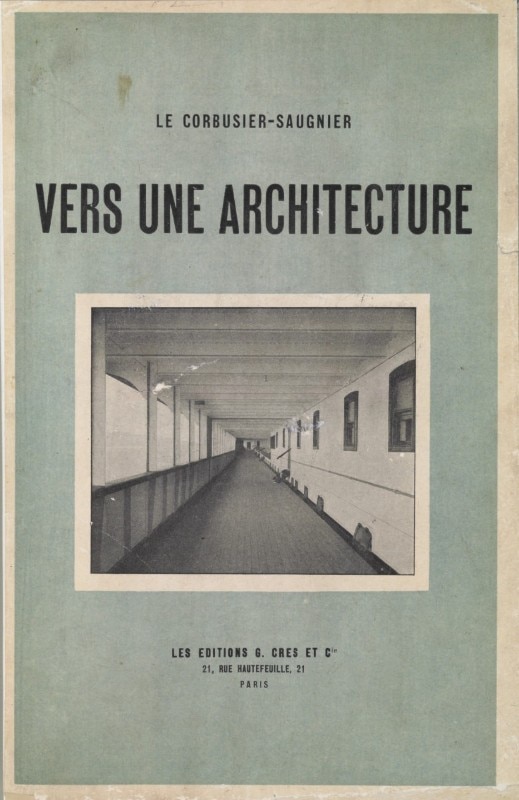

In all this, Swiss author managed to fully express his personality through his four souls: that of a painter, of an urban planner, of a decorative artist (term preceding that of a designer, which will be used only starting the 1930s), and that of an architect. Each one of these souls correspond to a book, the first being Vers une architecture (Toward an Architecture) published exactly a hundred years ago by the Parisian publishing house Crès, marking his decision to adopt the name of his maternal great-grandfather, though slightly altered, official: Le Corbusier – name which sounds like the name of a black-fathered bird. Extremely maniacal – he made his publisher sign an unconscionable contract which forbade them from making even the smaller changes to the layout of his books – Le Corbusier was initially set on entitling the book L’Architecture nouvelle (New Architecture) or Architecture ou revolution (Architecture or Revolution).

In this volume, Le Corbusier presented himself simultaneously as historian, critic, discoverer, and prophet.

Jean-Louis Cohen

In any case, the result was momentous. Paris back then was enveloped in a whirlwind that, as Giovanni Klaus Koenig wrote, was “capable of unsettling the entire art world, in the grasp of three people, none of whom was French by birth: Picasso, who was Spanish; Le Corbusier, who was Swiss; Stravinsky, who was Russian.” For this reason, 1923 was a very fruitful year for the artistic rappel à l’ordre and modernist revolutions: here the Romanian Brancusi realized the first version of Bird in Space, the Dutch Theo van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren designed Maison particuliére (Private House), the Belarusian Marc Chagall painted The Green Violinist, Ernest Hemingway published his first book Three Stories and Ten Poems and another American, Man Ray, directed his fist movie Le retour à la raison, while in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées Fernand Léger staged La création du monde based on a text by Blaise Cendrast, who was born in La Chaux-des-Fonds in 1887 as well, whereas every night Josephine Baker danced the Charleston at Folies Bergère.

The man who is intelligent, cold and calm has grown wings to himself. Men-intelligent, cold and calm-are needed to build the house and to layout the town.

Le Corbusier

In all this, Le Corbusier was both spectator and actor. From his book-manifesto translated into Italian only 50 years later (by Pierluigi Cerri and Pierluigi Nicolin for Longanesi) emerges a machinist spirit – fully supported only by Léger – which led him to dedicate the famous central section “eyes that do not see” to machines: steamships, aircrafts, automobiles. And yet, in the paragraph on aircrafts he wrote that “the house is a machine to be inhabited,” suggesting that it was possible, even desirable, to build houses in series like airplanes, namely with a light frame, metal beams, and tubular supports. “The man who is intelligent, cold and calm has grown wings to himself. Men-intelligent, cold and calm-are needed to build the house and to layout the town.”

As Reyner Banham fist noted, the very juxtaposition of two Greek temples (Paestum and Partenone) and two cars (1907 Beeston Humber 30hp and 1921 Delage Grand Sport) created a contrast similar to that created by the Futurist manifesto published on “Le Figaro” in 1909 between the race car and the Winged Victory of Samothrace. Afterall, it was Filippo Tommaso Marinetti himself who elevated the airplane to a mythological-artistic subject first with Le monoplan du Pape (Paris, Sansot 1912) and then by putting himself at the head of the Futurist aeropainting in the mid-1920s, after Toward an Architecture.

Le Corbusier kept on cultivating his machinist passion even in the following decade, publishing Aircraft (1935) with The Studio, the same publishing house with which his ideological rival, the French American designer Raymond Loewy, published The Locomotive: Its Esthetics (1937): the rivalry between airports and high-speed rails had just begun.

Opening image: Le Corbusier, Photo Joop van Bilsen / Anefo

The Trafic parquet collection: a new language for spaces

Designers Marc and Paola Sadler draw on now-extinct urban scenarios to create an original and versatile product for Listone Giordano.