The exhibition “Glass and Design. The creative process in the historic Murano glass factories of the 20th century” was the protagonist at The Venice Glass Week 2020 with the meeting “Once upon a time: the glass factories of the 20th century”, involving some of the last protagonists of an era unique in the history of glass and Murano. The exhibition project, hosted until December 31 in the spaces of Punta Conterie, retrace decade after decade Murano, in what it was in the last century: a hothouse of ideas, art, innovation.

We took advantage of the event to talk about the future and the changes of the island of glass with two people who were born in Murano: Caterina Toso, curator of the exhibition, glass historian and heir to the Fratelli Toso Archives, and Alessandro Vecchiato, until a few years ago co-owner of Foscarini, and now holder, together with Dario Campa, of Punta Conterie.

The vases and objects on display show a Murano in its golden years, between commissions from renowned designers or artists and unique pieces. But is this the only face of the island? “What is perhaps not so well known outside of Murano,” Caterina Toso explains immediately, “is that the glassworks, traditionally, were the first factories, the first industrial realities that made production on a very large scale. The artistic part, which is the one known internationally, was in fact only a minority percentage of what was actually the work of the glassworks. But clearly in more recent times, with the advent of industrialization, the volume of objects required has decreased. There is a whole series of objects that used to be mass-produced in Murano, but now there is no longer any reason to produce them. For example, until the second post-war period here were also made light bulbs. It is a merchandise category that has been taken away from the handcraft production, because obviously it is more convenient, more efficient and faster the industrial production”.

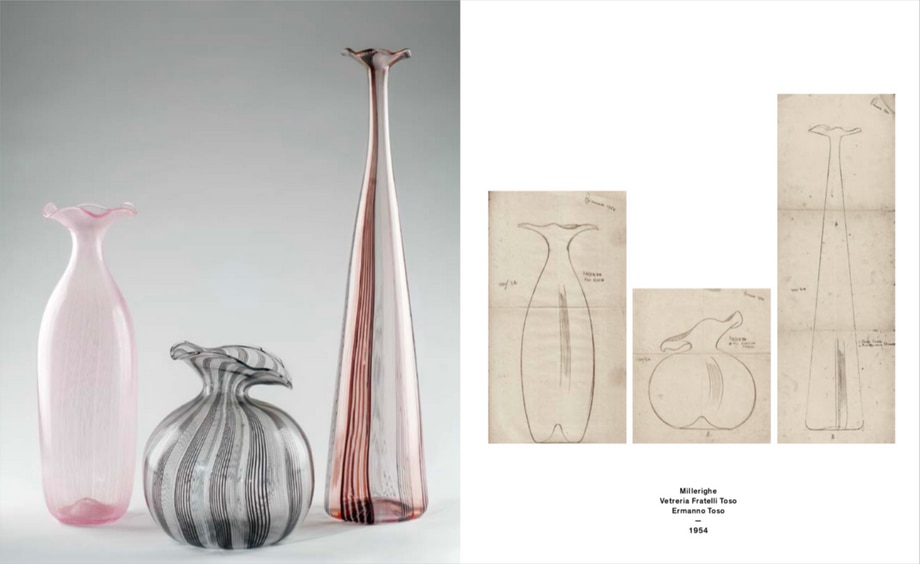

The works on display at “Glass and Design. The creative process in the historic Murano glass factories of the 20th century”, all original glass, come from important Italian and foreign private collections including the Holz Collection by the German Lutz H. Holz and the Vistosi heirs, some of which have already been presented at La Biennale di Venezia, others less well known: an original design by Hans Stoltenberg Lerche created by Fratelli Toso or the stained glass windows designed by Vittorio Zecchin for the doors of the SALIR company. A path from which emerge the names of some great 20th century glass designers, from Tomaso Buzzi to Fulvio Bianconi, from Ercole Barovier to Dino Martens.

“But the furnaces of such a large size, necessary for certain types of work” continues the historic Toso, “will hardly continue to exist looking around us, the trend we see is to have tiny furnaces that tend to revolve around a single master. The master and his plaza - a term used to identify helpers- do not exceed ten people. This tendency is a necessity to cut costs. The large furnaces have fixed costs, especially related to the use of gas that is difficult to sustain. They look almost more like artist’s ateliers”.

“I’ve never left Murano” begins the conversation with Alessandro Vecchiato. “When I left six years ago, I took a period of reflection. I found an island that has changed a lot in terms of glass production. Thirty years ago there were 150 companies with around 5000 workers, now there are still those 150 companies but with 800 employees in all. As the various craft sectors, the main problem are the workers, there is a lot of difficulty to find guys who want to start working glass. It’s turning into a handicraft activity of micro companies. There are very few companies that have seriality of product, they count on a few fingers of the hand, and many family micro-companies that focus on the art sector, very related to local tourism. There are few furnaces that can make a serial product, also because making a serial product means to know very well techniques and colors. Making a piece of art, five pieces can be different from each other. Different is the serial production of 100 pieces, and then repeat them after several months. You have to have a very wide knowledge of the subject.”

Another important theme for the future of the island is energy. The furnaces are still heated through natural gas, now disadvantageous both from a purely economic point of view and from an environmental one. “There is an enormous waste of energy. If we were in Japan, all this energy and heat would have been recovered. There are also big plant problems, where the only investment made in recent decades has been to reduce air pollution. I went into furnaces after thirty years and saw the same dust as then.”

How to move, then, to renew the island and keep this centuries-old tradition alive? According to Caterina Toso, it is fundamental “to aim at the renewal of the object itself. In the 1990s, one of the most produced articles were ashtrays. Today, in Italy, it is no longer allowed smoking in closed places, and this article happened to become no longer required. It is not, in my opinion, a renewal from a technical point of view, the furnaces will continue to exist, even those of large size, but thinking back to the category of merchandise, so trying to offer something that there is demand now.” But it immediately clarifies the need to reveal and be aware, for the users as much as for the artisans, of the inaccuracy of the term ‘tradition.’ “It is a closed mentality to think that traditional is exactly as it once was. The technique is traditional, but there comes a time when one can take advantage of knowledge and technological changes, which in my opinion do not distort the product in any way.”

And of the same opinion is Vecchiato. “At this time we must reverse the path by opening up to the outside world, also opening up to schools outside. We must create a real school on the island of Murano, not a teaching school that teaches theory, but a school applied with workers, internal or external. Which has never been done, Murano has always been very closed, and this problem makes the island, little by little, disappear. There are no spare parts at the level of workers, because there are no boys who go to work in the furnaces, and therefore the world of knowing how to do with hands has been abandoned.”

“The machine inside a furnace is the master and his team,” concludes the Murano entrepreneur. “It can have a more beautiful furnace, a spectacular ventilation, but if there is no master-machine, things are not done. Many factories, after the teacher retires, stop making that article. The company has not been able to get other employees to learn that skill.”