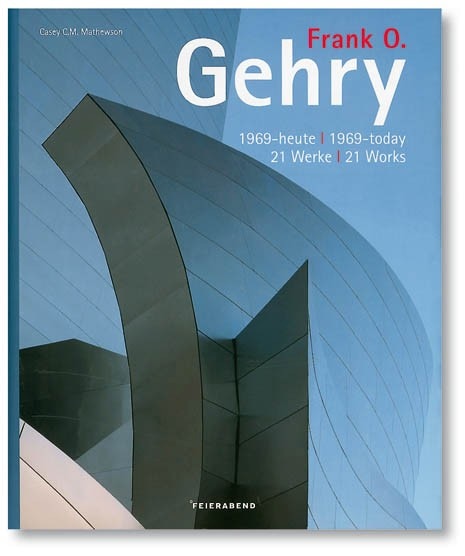

Frank O. Gehry 1969-today. 21 works, Casey C.M. Mathewson, Feierabend Verlag OHG, Berlino 2006 (pp. 600, s.i.p.)

This is a new book about Frank Gehry, the American architect who has risen to exceptional notoriety. He has invented sensational projects that are globally recognised and his works are never forgotten even after a cursory glance. In the face of such sensation Elias Canetti’s words on famous writers spring to mind: instead of remaining silent, they keep writing the same book. Any comment on the work of others requires true understanding. Nothing must be rejected or we lapse into mere after-dinner chitchat. We should welcome books such as this one edited by C.C.M. Mathewson because they record the most important works in detail. Five essays introduce the poetic of the American architect and identify certain recurrent themes: the concept of architecture as a sculptural object, the use of computer technology to create complex forms, the development of objects that give a sense of movement and contradictory structures that always tend towards a difficult harmony. The almost entirely photographic presentation of his most famous works (drawn from the archives of the Cologne photographic agency) is alternated with chapters on construction themes into which the works are grouped: the use of natural light and experimentation with different materials (wood, metal). The early architecture is manifestly reminiscent of the work of Claes Oldenburg (who collaborated on some of his projects). The artist who creates things-images works on standard everyday objects, enlarging them and exacerbating the colours, turning them into caricatures and making them so big that they seem to steal space from our lives. It is not, however, the models that are the real objects; it is the colour ads – because in this ill famed consumer society the publicity picture comes before the object. In the beginning, Gehry drew on the humble materials of the urban suburb, as did the Pop artists. He built with wire mesh and corrugated metal. He transferred what had been attempted in painting and sculpture to architecture. In the Santa Monica house, extensively illustrated in the book, he uncovered, gutted and deconstructed a prefabricated house. Then came the Vitra Design Museum and the American Center in Paris. As you progress along this amazing photographic journey through his most famous works (Walt Disney concert hall, Bilbao and more), you suddenly think of when Le Corbusier and Xenakis designed the Philips Pavilion in 1958. The French architect anticipated certain features of contemporary architecture – that based on non-linear dynamics – and that of Gehry, for example, made of buildings generated and cut on the computer, by using the distortion of mathematical and structural curves. Moreover, “I will not give your pavilion a facade,” wrote Le Corbusier, “but I will compose an electronic poem… the pavilion will be a stomach that can absorb 500 spectators and automatically evacuate them at the end of the spectacle.” With the visual bombardment of forms in movement capable of reaching mass culture, he triggered the museum-spectacle-market-fair-exhibition-emporium of architecture that is forever condemned to be contemporary and avant-garde. The “spectacular” becomes a value; innovatory (present-day) technology, extraordinary means and a modern linguistic universe instinctively make the ancient gestures (of building) more immediately spectacular and produce an amazing commercial success. Like huge stomachs, this architecture swallows mass events, rivers of interviews, advertising and sometimes aggressive publicity. It generates movement; it is photogenic and, most of all, recognisable from the first frame. There is nothing bad in that but we must also be clear that a work of architecture must win over chance and channel emotions. It must be entirely rooted in the spirit; technical accomplishment is but a rigorous materialisation of the concept, almost a fabrication. In Plato’s Phaedrus at the beginning of the dialogue, the protagonist, Phaedrus, and his life master, Socrates, walk outside the walls of Athens and follow the Ilissus River until they reach a holy wood, where they lie down to read a work about love. But every sentence leaves complex problems unanswered and every answer raises fresh questions, quickly causing the friends to forget the composition and enter into a discussion on a variety of subjects until, in a giddy crescendo, they start to wonder about the very structure of the cosmos. What if, like this book read by Phaedrus and his master, architecture were the trigger? We must distinguish between those who insist on prolonging the chain of innovation, squeezed into exasperated languages, and those who are trying to make their work reveal aspects of reality that concern everyone. If they succeed, a work can take the spectator beyond the physical boundary of the work itself. The reader, and the scholar, should pause for a moment and look at two small buildings (places of suffering, alas) in the monograph, the Ronald McDonald Centre and Maggie’s Centre, and draw their own conclusions.

Luisa Ferro Professor of Architectural Design