Have you seen the picture of the little girl and her puppy being rescued from Hurricane Helene? And if you have, did you believe it? More importantly, did you stop to wonder why you believed it? If the hurricane hadn't been covered by the media, few would have given the image much credibility; however, because the event was real, many people, including Mike Lee, a U.S. senator from Utah, were fooled by the deception. This anecdote—like so many others—illustrates that misinformation doesn't depend so much on the realism of images, but rather on the source and the context in which the story emerges.

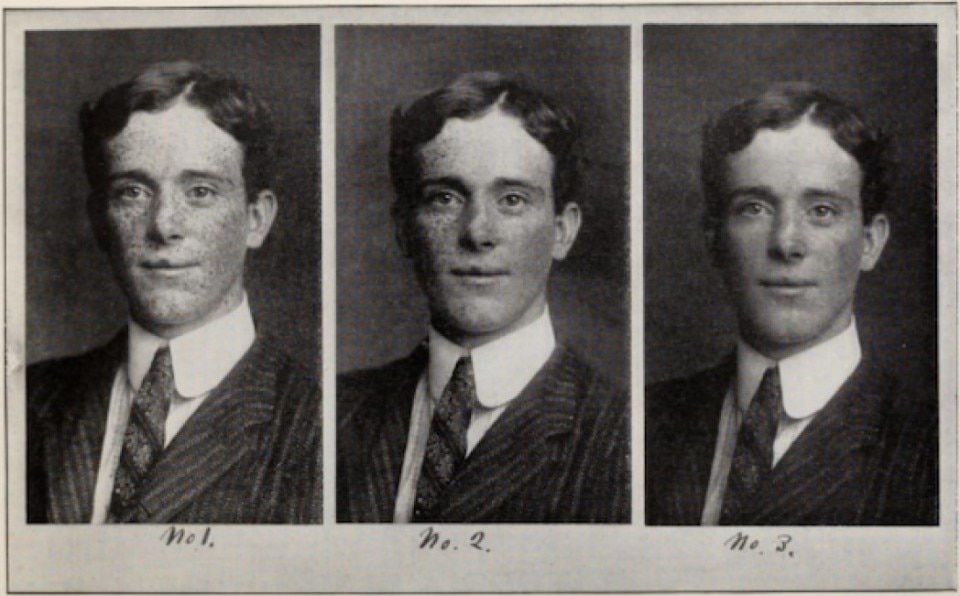

With the rise of generative AI, many media outlets have sounded the alarm about the demise of truth in photography and the media more broadly. The Verge, for instance, recently published an article titled "No One Is Ready for This" a rather placid and understated headline with an even more calm conclusion: "we're fucked." This fear is not new; as far back as 1897, the New-York Tribune declared that trust in the truthfulness of photography had "burst," thanks to the spread of photo manipulation, using language eerily similar to The Verge.

In 1911, tourists in Washington D.C. could even buy fake photos of themselves posing next to President Taft, which caused concern among government officials to the point that a law was proposed to ban manipulated photos without consent. The proposal attracted media attention but was never passed. Some, like American Photography magazine, opposed it, fearing it could open the door to frivolous lawsuits.

The credibility of images depends less on how realistic they look and more on who spreads them and the context in which they are seen.

But is it truly technology that determines the truth of an image? Consider the First Gulf War: on the night between February 26 and 27, 1991, U.S. aircraft destroyed Iraqi units retreating along a highway in Kuwait. The photos that were released depicted the infamous "Highway of Death," a road filled with charred vehicles but no bodies. Were the corpses incinerated, or removed before the photos were taken? We’ll never know. Those images were used to bolster the narrative of a swift and clean military success, leaving out the brutal reality of war. This demostrates that even without retouching, a photo's documentary value is shaped by decisions about what to reveal and what to conceal. Framing itself is the first lie, to paraphrase Susan Sontag, author of On Photography.

It’s not the quality of the representation that lends it credibility, but the context in which it is shared. The renowned writer Arthur Conan Doyle, father of the world’s most rational detective, believed in the famous “Cottingley fairies” photographs—amateur montages showing enchanted creatures—not because of their realism, but because, as an esotericist, he was predisposed to believe in them.

Similarly, during the Stalinist regime, the successful removal of inconvenient figures from official photos was supported by the authority of the government, as in the case of Nikolai Yezhov during the height of Stalinism. In both instances, the truth of the images stemmed not from their visual content, but from the narrative that accompanied them and the authority that legitimized them.

A powerful example of the ambiguity of images as historical testimony comes from the photographs taken by the Sonderkommando at Auschwitz. These photos, secretly captured by prisoners compelled to work in the crematoria, are among the very few images that document the horrors of the extermination camps from the inside. The images are grainy, blurry, and often hard to interpret: indistinct figures move in the background, while bodies pile up into the shadows. Their testimonial value doesn’t stem from visual clarity, but from the story they tell. They embody the desperate will to bear witness to horror, even at the cost of death, and it is precisely this context that grants them immense significance.

Even in the age of Photoshop and AI, no matter how manipulated or generated an image may be, it will only gain power if it’s disseminated by a credible authority or paired with a persuasive context and narrative.

A particularly revealing case is that of the climate crisis. Despite a vast amount of scientific evidence—ranging from satellite photos to videos of extreme weather events and empirical data clearly showing the acceleration of global warming—there are still movements that deny or downplay the issue. Climate science has achieved near unanimity in its diagnosis, backed by an abundance of visual and tangible proof: So why do some people still deny the existence of the climate crisis?

Their testimonial value doesn’t stem from visual clarity, but from the story they tell.

Fear undoubtedly plays a key role, but so do large fossil fuel companies and economic lobbies, which have invested significant resources intodiscrediting climate science, sowing doubt through compliant media outlets. It’s not merely a few fringe conspiracy websites: as many studies suggest, it’s the seemingly trustworthy sources of these narratives that make them so influential. If we come across UFO videos on an obscure website, we don’t give them the same weight as if we saw them on the evening news or in a major newspaper—even amidst the ongoing media credibility crisis.

Thanks to the internet, we’ve witnessed an exponential rise in the number of people with access to information compared to the past. False beliefs no longer spread solely through official channels or institutional authorities, but also through the amplification of social media. Yet even in this case, public opinion is largely shaped by profiles with a vast following.

The multiplicity of information sources and the subsequent counter-narratives create a fragmentation that complicates the formation of mass consensus, though this still tends to coalesce around major charismatic figures, much like in the past. One of the most destructive conspiracy theories in history—the witch hunts—spread across Europe between the late Middle Ages and the early modern period, long before photography, photo manipulation, Photoshop, and AI. If, as The Verge puts it, “we’re fucked,” well, it seems we’ve been fucked for a long time.