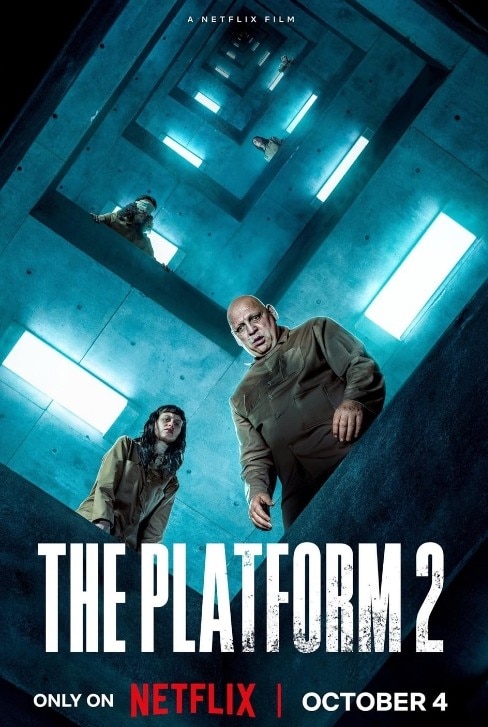

For those with a Netflix subscription, the arrival of The Platform 2 was a throwback to March 2020, when in several countries around the world the first lockdowns had begun, and awareness was growing in others that it was better to avoid contact with people as COVID-19 was spreading.

The Platform is a Spanish movie, released in its home country in 2019 and distributed worldwide by Netflix right about the same time, when many were subscribing to the platform, aware of the long time they would spend at home. Many, therefore, watched a movie whose entire meaning is based on an idea of design and coexistence, on a structure that, by its very conception, directs people towards certain relationships, both in terms of power and control.

In a period of greatest distrust toward others, the movie arrived with the perfect metaphor for what people were beginning to fear: others are watching us, we must act for the common good and not be selfish, and the survival of those in weaker positions depends on our actions. In 2020, The Platform was a massive success, predictably. Today, everything is different, and the same platform has a completely different meaning.

At the center of the story is an imaginary and fantastical prison, which is structured vertically with more than 300 floors connected by a gigantic square hole in the center of the single room (the cell), where people of various backgrounds and different pasts are imprisoned. There is, therefore, a concept of negative design, created by removing part of the ceiling and flooring, which changes the lives of the characters.

From each floor, one can see both those below and above, simply by leaning out. In this square hole, a platform full of food descends every day, stopping at each floor for several minutes. Those on the upper floors eat first and have a wide selection, while the lower floors have less and less to choose from; those on the lowest floors can only hope that something is left. Every month, the prisoners change floors: those who were above can end up below and vice versa, those who were tormentors yesterday can be victims today; those who complain about the selfishness of the upper floors today can test their own altruism tomorrow.

The mere construction of the cells in The Platform is a cue for a different kind of interaction between people. And the most interesting thing is that this, like the movie’s metaphor, is immediately understandable to everyone.

The strength of The Platform and of The Platform 2 lies precisely in the fact that it is not difficult to grasp what these movies are really about, what their subject is, and what they want to say about the societies we live in, the scarcity of resources, and especially human behavior. It is an extremely accessible metaphor, with many different levels of interpretation.

The first movie focused on predatory mechanisms, on how those in privileged positions do not think about those below, and how, when someone who has suffered for a long time suddenly becomes privileged, instead of wanting to change something, they take advantage of it, behaving like those who came before them. On the other hand, the second movie focuses on the forces in every society that push for subversion, those that seek a new, fairer organization where everyone can thrive. However, the means used to impose change are almost worse than the status quo they are fighting against.

What remains unchanged from one movie to another is the fact that all this manifests through the same design, that is, the same hole that makes the levels interconnected and allows the platform with the food to pass as if by magic. There are no visible runners or cables, and the platform seems to descend from nowhere. But most of all it is the very idea of communal life, in a sort of endless apartment building where prisoners can see into each other’s cells, which is even stronger in this sequel.

Social control, in an impossible building without walls and (almost) without roofs or floors, is total. There is no need for security cameras or government entities to listen to prisoners: simply to design residences where the intrusiveness of others is almost complete. The mere construction of the cells in The Platform is a cue for a different kind of interaction between people. And the most interesting thing is that this, like the movie’s metaphor, is immediately understandable to everyone.

It does not take a degree in architecture to grasp what could happen when people’s sustenance directly depends on others, and everyone’s actions can be monitored. Nor does it take a degree to understand that the brutalist design, made of unadorned concrete without finishing touches, is the perfect representation of a society reduced to the essentials: everyone’s primary concern is survival – eating – and if each prisoner were to eat equitably, there would be enough resources for all.

The Platform 2 expands on what this simple design can convey to everyone, namely that the separations between the spaces we live in – transitional areas, shared spaces used as buffers between different private areas – are not just functional to social life but essential to the fabric of society.

Increased proximity, greater intrusiveness, and more opportunities for people to be together, not in public spaces but in private ones, become the spark that ignites the worst in humanity. The architecture of urban spaces, interiors, buildings, apartment buildings, and individual homes is not just a way to improve functionality in life but also one of many possible tools to shape interactions between people.

The separations between the spaces we live in – transitional areas, shared spaces used as buffers between different private areas – are not just functional to social life but essential to the fabric of society.

The revolution we witness in The Platform 2, led by a group of rebels who aim to make everyone eat only their fair share so that food reaches the lower levels, is a dictatorship imposed through violence, driven by a prophet-like figure, full of unquestionable commands, and fueled by denunciation, suspicion, and rigidity.

Watching what others do in their cells is never a neutral act: we see characters doing it with disgust, others with a sense of warning, and some with fear or threat. Ultimately, it becomes clear that to bring out people’s lowest instincts and reveal their impulses, it is not only necessary to place them in situations of mutual dependence but also to design a specific space, carefully thought out for that very purpose.