Bedtime was my nightmare. Unlike other children, I wasn’t afraid of the dark; I was terrified of the hallway in our house. […] My bedroom was the last one at the end, so I had no choice but to walk through the entire hallway. […] that hallway was filled with curtains and windows, dimly lit by low lights, and it terrified me. […] It was a perfect form of terror: pure and unconditioned.

Dario Argento, Paura, Einaudi, 2014

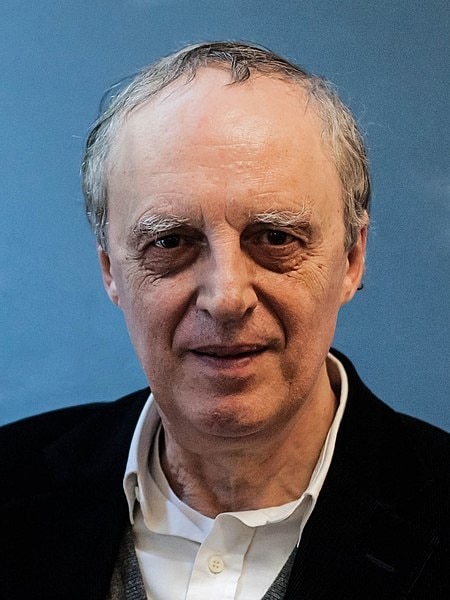

Born in Rome in 1940 to a film producer and a photographer, Dario Argento has been immersed in images since childhood. From the 1970s to the present, he has directed around 20 films and scripted twice as many. He has ventured into television, appeared on camera in cameos and acting roles, and significantly influenced Italian genre cinema, bringing it to the international stage and becoming a cult director.

Often dubbed the "Italian Hitchcock," Argento drew inspiration from and paid homage to the "Master of Suspense" in several films. Alfter all, Hitchcock remains an essential reference for filmmakers, despite being overlooked by critics, at least in the United States, for much of his career, until François Truffaut’s 1966 book-length interview, Hitchcock/Truffaut, highlighted his genius for future generations.

From this text, we can glean that suspense and fear are the most intense representations of a film’s narrative and visual material. Suspense scenes are "privileged moments" that draw the audience into the action and leave a lasting impression. In Hitchcock’s films, as in Argento’s, every moment is a "privileged moment" that heightens tension and emotions in the viewer. Argento, while distinctly Italian, managed to absorb and transcend Hollywood conventions of thrillers through aesthetic research that maximized the emotional impact of his scenes. This created a unique and unmistakable style, with set designs and urban settings as foundational elements. Domus has analyzed the evolution of this distinctive style.

Definition of a canon: The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970)

Argento sets his debut film, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), in Rome, establishing a foundation and synthesis of the elements that define his cinema: an initial, disturbing crime; a crucial detail the protagonist fails to grasp − key to unraveling the mystery; include a preference for bladed weapons; the psychopathology of trauma, a killer in black gloves, dark hat, and raincoat; close-ups on objects and eyes; the killer’s point of view; and the use of sound as a primary narrative device; photography as a tool to skillfully accentuate spaces. And then doors, hallways, and windows. Argento “strangles” and transforms everyday elements by reinventing their emotional resonance. The narrative unfolds in various settings: an art gallery with stark white walls and floors, the protagonist’s nearly windowless – there are only two small openings − apartment, and the bourgeois home of the Ranieri family, who own the gallery.

For exterior locations, Argento chose EUR, the then Rome Zoo, fog-shrouded streets on the Aventine Hill, and sidewalks in Trastevere and Testaccio, which he claustrophobically confines into "hallways" for characters to traverse in flight. According to some theories by reconstruction enthusiasts, the hippodrome where the killer spots one of the victims is not Capannelle but the one in Agnano, Naples. This demonstrates Argento's ability to fragment urban spaces and foster geographic indeterminacy in his debut film. His use of the "door" element is particularly emblematic, with its persuasive horror amplified by the cinematography. Argento employs a subjective shot from one of the victims, following their gaze from the door, through which light passes, to the extinguishing of a cigarette in the ashtray, then back to the door framing the killer’s silhouette. After this film − and perhaps even more so after Suspiria − it is impossible to look at a simple door the same way again.

- Title:

- The Bird with the Crystal Plumage

- Directed by:

- Dario Argento

- Produced by:

- Seda Spettacoli and Central Cinema Company Film

- Distribution:

- Titanus

- Year:

- 1970

Turin + Rome = Deep Red (1975)

With the two films that, along with The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, form the so-called "Animal Trilogy" − The Cat o’ Nine Tails (1971) and Four Flies on Grey Velvet (1971) − Argento explores his preferred settings for shooting thrillers and begins experimenting with the composition of the ideal city, creating a disorienting collage that merges Rome with his beloved Turin. However, it is in Deep Red (1975) that this blend achieves iconic dimensions.

«Thoughts of death cling to environments like solid cobwebs,» it is said in the film, and Argento ensnares us in this urban "web," ostensibly Roman but evidently of Turin: a metaphysical Turin, especially in the ecstatic desolation of Piazza CLN. Here, the director places a fictitious bar − as a homage to Hopper’s Nighthawks (1942) − where the protagonist witnesses the murder of the medium, attacked in her apartment but killed by a shard of glass from a broken window piercing her throat. that triggers the entire story.

In Argento’s films, elements of domesticity become not just vehicles of terror, but actual weapons: windows, the corners of Giordani’s (Glauco Mauri) living room fireplace, the bathtub filled with boiling water in which Righetti (Giuliana Calandra) is drowned, and the elevator that closes the curtain on Clara Calamai’s murderous spree. Once again, a piece of furniture holds the key to the mystery, placing the killer in plain sight of the protagonist − and the audience − from the start: in the unsettling hallway adorned with esoterically inspired paintings, a mirror reflects the face of Carlo’s mother, though both we and David Hemmings initially believe it to be a painted canvas.

In these domestic spaces, we begin to see the Art Deco elements that will become predominant as the paranormal increasingly infiltrates Argento’s vision: here they appear both in the medium’s apartment and Giordani’s, while Calamai’s more baroque and decadent dwelling is dotted with portraits of the actress herself, which, like mirrors, multiply her image, subtly urging us to focus on her character. And then there is the "villa of the screaming child," Villa Scott − a work by Pietro Fenoglio and a magnificent example of Turin’s Art Nouveau − with its walled-up window concealing the domestic secret

- Title:

- Deep Red

- Directed by:

- Dario Argento

- Produced by:

- Rizzoli Film and Seda Spettacoli

- Distribution:

- Cineriz

- Year:

- 1975

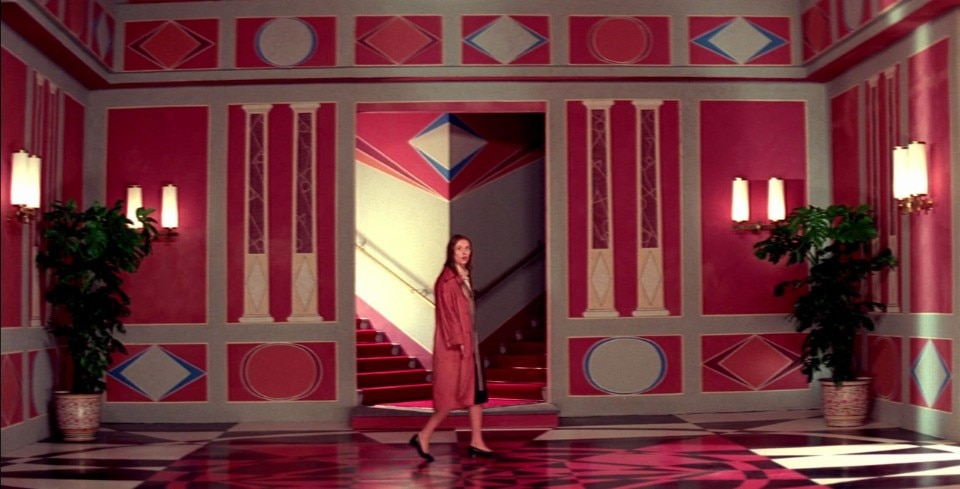

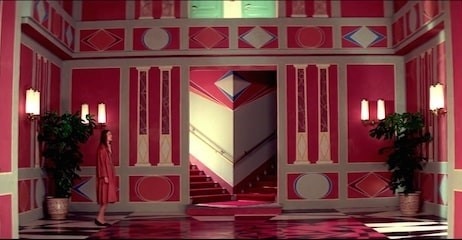

A dark fairytale in the Black Forest: Suspiria (1977)

Perhaps his masterpiece, certainly the pinnacle of his stylistic evolution, Suspiria, inspired by Thomas de Quincey and the stories Daria Nicolodi’s grandmother told her granddaughter, emerges as a horrifying evolution of Disneyesque atmospheres blended with German Expressionism, taken to the extreme by the use of Technicolor and Luciano Tovoli’s photography. The beginning is that of a fairy tale, telling the story of dancer Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper) arriving in Freiburg to join a prestigious dance school. Here too, light shapes both external and internal environments. Horror is introduced through sound by the airport exit door. Then a taxi ride in the rain, through an almost stylized forest where only the trunks of trees can be glimpsed.

The arrival at the school, modeled on the inspiration of the late Gothic Haus zum Walfisch, The Whale House − where even Erasmus of Rotterdam lived − is marked by the fateful moment when the protagonist perceives a message that she will only realize later − the directions from a fellow student to discover where the witches gather. Before taking us into the soft and unsettling architectures of the school, Argento follows the first victim of a suffering that, unlike previous films, does not stem from trauma, but is pure Evil: Pat (Eva Axén), recognizing the demonic nature of the academy’s teachers, flees from a friend and takes refuge in a palace that is a triumph of dreamlike Art Deco style, filled with geometric shapes tinted in pastel hues. If the clues were not clear enough, Giuseppe Bassan, the set designer, inserts the silhouette of the Empire State Building in the bathroom windows, which once again become weapons in the hands of Death.

We then find the metaphysical dimension of squares in the dark Königsplatz in Munich − the site of Hitler’s rallies – where Flavio Bucci’s character is assaulted. He crosses the square after drinking in the beer hall where the Führer organized the failed coup in 1923: a chilling path to subliminally suggest the nightmare to come. It is the principal colors − blue, red, green, gold − that tint the organic interiors of the dance academy, whose Art Nouveau-inspired doors, deliberately made oversized by the director to appear even more imposing on the students, transform into thresholds of terror. Suzy’s bedroom wallpaper is a stylized depiction of a demonic scale pattern, while Madame Blanc’s studio is articulated in a circular garden decorated with Escher-inspired shapes. Once again, a piece of furniture holds the key to understanding a secret: the carpet in the studio muffles those footsteps, which, if followed through the ominous vermilion corridors, lead to the lair. While the staircase decoration recalls the nature of the congregation: a snake that dies if its head is cut off and collapses.

- Title:

- Suspiria

- Directed by:

- Dario Argento

- Produced by:

- Seda Spettacoli

- Distribution:

- P.A.C.

- Year:

- 1977

The demonic dwellings of Architect Varelli: Inferno (1980)

If the dance academy in Freiburg hosted followers of Evil, in the second chapter of the "Mothers Trilogy," it is the buildings that assume the role of true characters. Pestilential houses, emitting foul odors and polluting the neighborhoods in which they were erected, designed by the architect and alchemist Emilio Varelli at the behest of Mater Suspiriorum, Mater Lacrimarum, and Mater Tenebrarum, these houses "are eyes through which they see." Three sisters, three dwellings, three cities: Freiburg, Rome, and New York. Inferno traverses the architectural originality of the Coppedè district in Rome − where Mater Lacrimarum lives − before focusing on the neo-Gothic New York palace dedicated to the youngest and cruelest Mater Tenebrarum. An angular, essential neo-Gothic style, abandoning the visceral softness of the sites in Suspiria. Here, it is not the building that shapes itself around its residents, but it rather lives and acts autonomously.

The dreamlike interiors focus on black doors and vermilion walls, baroque apartments, multiple staircases, faux floors, and flooded undergrounds, while Romano Albani’s photography blends blues and reds into synesthetic, sweetish pinks and purples, returning to us all the olfactory connotations of the demonic houses. We will discover that Varelli is organically connected to what he has designed, revealing the true nature of the building: the palace is the body, the bricks are the cells, the veins are the corridors and passages. Unjustly ignored or misunderstood, Inferno represents Argento’s accomplished attempt to articulate and represent the indecipherability of evil.

- Title:

- Inferno

- Directed by:

- Dario Argento

- Produced by:

- Produzioni Intersound

- Distribution:

- 20th Century Fox Italia

- Year:

- 1980

The rarefied Minneapolis of Trauma (1993)

Argento rides the wave of the 1980s by returning to the Roman thriller setting (Tenebrae, 1982), passing through the meadows and mountains of Switzerland (Phenomena, 1985), and arriving at the operatic spaces of Verdi (Opera, 1987). However, he chooses Minneapolis as the setting for the film that marks his first collaboration with his daughter Asia, along with the ever-unsettling Piper Laurie (Carrie, Twin Peaks). Hitchcock references abound in this thriller, where the paranormal proves to be a mere pretext in the hands of the killer to exact revenge. The drama of anorexia is portrayed in broad daylight, juxtaposed with a girlvs search for truth as she witnesses, or believes she witnesses − the deception of sight returns − her parents being decapitated.

The domestic spaces of the 19th-century Petrescu villa are contrasted with typically American settings such as long bridges, big motels, and bustling diners. For both exterior and interior shots, Argento employs the use of a particular smoke to gradually create a more rarefied image for the faces and environments. The wooden house on the lake, where Christopher Rydell’s character lives, echoes the Crystal Lake Camping of the famous slasher Friday the 13th (1980), which in turn pays homage to the mythological Bay of Blood (1971) by Mario Bava, to whom Argento himself owes a great deal. The protagonists are freed from the nightmare by the innocent (?) hand of a child wielding an object of death, much like the small "solvers" in Bava’s film − including Nicoletta Elmi, who worked with Argento in Deep Red − while with the decapitation of Brad Dourif decapitation by elevator, the director whirls back to reference himself.

- Title:

- Trauma

- Directed by:

- Dario Argento

- Produced by:

- Adc, Overseas Filmgroup

- Distribution:

- Cecchi Gori Group, Silvio Berlusconi Communications

- Year:

- 1993

Real murder in a virtual environment: The Card Player (2004)

Belonging to the less successful season of his filmography, with The Card Player Argento explores the virtual space of the internet, where people play a true game with death: not like Bergman’s chess but a less philosophical video poker whose rules are dictated by a killer motivated solely by rejection. The computer screen becomes an intangible place of concrete murders, captured in real time with the webcam during matches with the police. Argento is back in Rome, specifically in the Gianicolo suburb: the Brasini’s Good Shepherd Complex hosts the police station, while in the Botanical Garden located in the park of Villa Corsini, conceals the hideout of the Card Player with its niches and seventeenth-century staircases.

The nighttime chase takes place in the heart of the historic center, but the vivid suspense of the escapes in narrow outdoor "hallways" is a distant memory. The settings lend themselves to the photography of Benoît Debie, a colleague of Gaspar Noé, with whom he worked on Irréversible (2002) − and later on Enter the Void (2009) and Climax (2018) − but, the absence of a compelling narrative and the now lost ability to construct those "privileged moments" of suspense, which have established Argento as a master of the seventh art, prevent even the most skillful collaboration from restoring strength to the vision.

- Title:

- The Card Player

- Directed by:

- Dario Argento

- Produced by:

- Medusa Film, Opera Film

- Distribution:

- Medusa Distribuzione

- Year:

- 2004

Between the city and the woods: Dark Glasses (2022)

Even in Dark Glasses, Dario Argento’s latest effort, there are no strong motivations or triggering traumas underlying the actions of the killer, almost dragging the viewer into a kind of concreteness and banality of horror. We are back once again in a sun-drenched Rome, where the structures of modern high-rises blend with those of luxury hotels, in a continuity that brings together the center and the suburbs. The film doesn’t shine for the characterization of its environments, rather anonymous and lacking in a recognizable style − the architectural and design vertigos of the 1970s films irretrievably belong to the past − rather for the dichotomies it revolves around: city and forest, light and darkness, vision and blindness.

Around these poles, Argento shapes the actions of the characters, especially that of Diana (Ilenia Pastorelli), an escort who, in past screenplays, would have appeared as a mere disposable supporting character but here, instead, takes the role of protagonist, but also that of the killer, whose identity is revealed halfway through the film, subverting the very canons the director himself had invented.

After all, the deceptions of vision that characterized works like The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red, or the more recent Trauma are not feasible under conditions of blindness: only escape remains, in narrow hallways or dark woods. If the airport in Suspiria was constructed as the antechamber of the nightmare, in Dark Glasses it represents the salvific landing after horror. Moreover, Argento seems to suggest that it also embodies a vast, impersonal, and chaotic space, amplifying the protagonist’s sense of loneliness – after all, who isn’t afraid of loneliness?

- Title:

- Dark Glasses

- Directed by:

- Dario Argento

- Produced by:

- Urania Pictures, Getaway Films, Rai Cinema

- Distribution:

- Vision Distribution

- Year:

- 2022

The other side

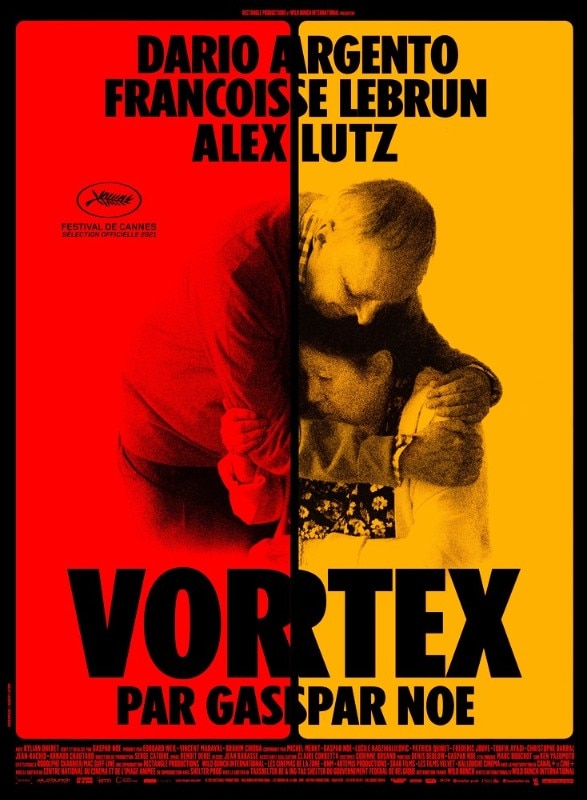

Dario Argento is undeniably a cult director who has significantly contributed to the history of cinema. But is he still capable of offering something exceptional to his audience? It would seem so. He surprised us once again very recently, by stepping away from his own role to cross a threshold, that is to step in front of the camera and be escorted towards death by the Argentine director Gaspar Noé in his Vortex (2021).

The claustrophobic domestic setting of a Parisian apartment overflowing with traces of a life already lived, becomes a true preamble to departing from the world: the split screen isolates the two characters and evolves into a burial niche that neither a French cinema icon like Françoise Lebrun nor our Argento, who in fifty years of career has condemned hundreds of characters to death, can escape. There are no murderers but the unstoppable vortex of old age, illness, the inevitable disintegration of mind and body. The greatest horror, to which our master of suspense surrenders, consecrating the journey of a lifetime dedicated to exorcising it.

- Title:

- Vortex

- Directed by:

- Gaspar Noé

- Produced by:

- Wild Bunch, Canal+

- Distribution:

- Mubi, Prime Video

- Year:

- 2021

Opening image: Dario Argento, Suspiria, 1977

Ethimo's latest collection is all about weaves

Inspired by the traditional craftsmanship of Eastern Spain and patios, the new collection designed by Studio Zanellato/Bortotto reimagines the aesthetics of comfort.