Everytime we come across the word icon, long overused and deprived of any meaning, and with those sacred faces that shaped popular culture, we often end up looking back at the 1960s. We dip in the decade like a blindfolded kid does in a parish council fête from a wicker basket, with the awareness that whatever they’ll extract there’ll be a winner. Among them, with a woven wicker bag in hand, there was, still is and will be Jane Birkin, born Jane Mallory Birkin, but simply Jane B for the close ones, like the title of one of the most acclaimed compositions her former partner and companion of erotically whispered songs Serge Gainsbourg wrote for her.

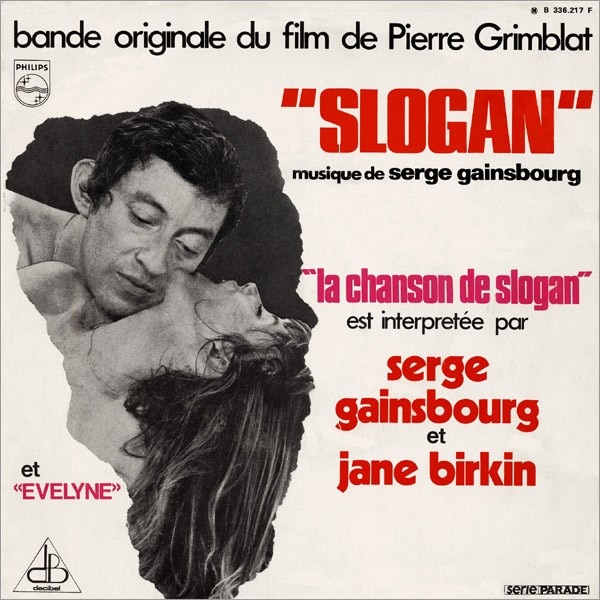

Passed away at the age of 76 in her Parisian flat, the subject Jane Birkin subject was iconic in her power – a condition and privilege of few – to transcend her golden age, her jeunesse dorèe spent in London first, Paris then. She accomplished so by nourishing and fuelling styles and lifestyles always anew yet timeless, like the essential grace of her album arrangements or like a white crepe top worn nonchalantly over a pair of denim flares, mary janes and a cigarette caustically burning in her fingers. Her essential look had its counterbalance in Serge Gainsbourg’s pompous pinstripe suits and long sideburns, curly and greasy, his custom-made white leather winklepickers and the silver Star of David charm, bought from Cartier and worn around the neck to rub in the face of the most conservative Frenchmen that that edgy, riotous Jewish had made it.

Beyond the subject-Birkin, the actress and model deserves the icon status, above all, for her osmotic ability to turn everything she interacted with into something iconic, like a King Midas of etiquette. Although she was never a designer, Birkin had the magnetic power to take common objects – like a woven wicker bag or a pair of jeans covered in patches – elevating them, through effortless and flawless endorsements, free from the artifact superstructures imposed by contemporary communication, into aesthetic cornerstones transversal to trends and generations. Her looks were timeless because they were spontaneous, mirroring her approach to life. Speaking to Vogue in 2016 in regards to her refractoriness to the cameras, she said “real life is what I was best at”. That’s why her diaries, penned since 1957, and later collected in two volumes, offer an intimate insight into her life which, despite extraordinary, one can identify with, because simple.

The song, joked Jane, ‘when I die, will be the tune they play as I’ll go out feet first’.

Like the time in 1984 when, on a flight from Paris to London, the content of her famous straw handbag fell out of the overhead locker. In a twist of fate, jet-set oblige, sat next to her was Jean-Louis Dumas, chief executive of Hermès, who listened to the actress and model’s complaint about the struggle of finding a decent leather weekend bag, equally stylish and functional. The Birkin, one of the most expensive and exclusive handbags on the market, was born.

Before the consecration of fashion, it was the erotic magazines that celebrated the enigmatic charm of Jane B, which saw in her persona and in the duets with Gainsbourg a heroine of the sexual revolution. With her, like in a now collectible issue from 1973, was Brigitte Bardot, her nemesis both aesthetically and in her love liaison with Gainsbourg, who had originally written his “Je T’Aime...Moi Non Plus” with BB in mind. These reportages graced the publication with distinctive erotic intellectualism, certainly not chaste but charmingly cheeky. The same that Jane Birkin gracefully portrayed.

Take the cover of issue 61, from 1969, the couple’s “année érotique”, in which Birkin poses on an Elda armchair by Joe Colombo. It was just one of the several modernist design chairs on which Jane B would be photographed over the years, like the 1967 Blow Inflatable Chair by De Pas, D'Urbino, Lomazzi for Zanotta.

In 1974, the magazine published another instant-classic editorial. This time shot by Francis Giacobetti, the Caravaggio-style chiaroscuros enhanced by the velvet outfits of Jane and Serge and by hints of Sapphic violence summed up the relationship, which today we wouldn’t hesitate to dub toxic, between the two.

It can be argued that this typical 1960s It Girl attitude, a whirlwind of eroticism, bubbly flamboyance, aplomb, baroque drama, impulsiveness in loving and suffering accordingly, submission but also fatal seduction, set a gold standard, as part of an eternal process of citationism elevated to lifestyle, as much adored by the teenage girls of the roaring years of Tumblr’s as celebrated by the fashion industry.

On the other hand, her spontaneous versatility as a model, singer, actress, arbiter elegantiae, and influencer ante litteram, confirms her enduring relevance in contemporary socio-economic and communication practices.

It is not wrong to see in Jane Birkin, in her ephebic, almost androgynous features, and in her relationships with mature musicians – the marriage at 19 to English composer John Barry, then the encounter at 21 with French crooner Serge Gainsbourg – the vanguard of the Heroin Chic style of the 2000s. Her gap-toothed smile, unorthodox in the eyes of traditional fashion, became with Jane B a new standard that over the years would make figures such as Kate Moss and Danni Miller to stand out. Or simply think of the ad campaign symbol of Heroin Chic and Indie Sleaze iconography, Rimmel’s famous “Get The London Look”.

Born in England to a war hero who served in the Royal Navy and to actress Judy Campbell, Birkin was able to embody like no other the aesthetics of Paris. She shaped a now institutionalised and romanticised image of her adoptive city, influencing in turn several other non-French-born icons who have nonetheless become heirs to her etiquette, such as Carla Bruni and Alexa Chung. No wonder French President Macron saluted Jane B as a “French icon”.

The yè-yè style she contributed forging alongside figures like pop star Françoise Hardy became France’s libertine but not less intellectual answer to the Swinging London, subverting with provocative light-heartedness centuries of male gaze in shaping the prototype of the woman in the entertainment industry. The subversion of something so far taken for granted and stereotyped, like “L’Anamour” the song in Jane and Serge’s first joint album, a negation of love becoming a lustful anthem.

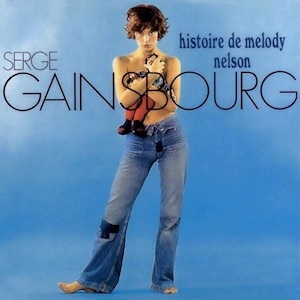

This was well understood by Gainsbourg who, at two key moments, had fun re-imagining Birkin. He did so on the cover of the concept album “Histoire De Melody Nelson”, in a shot by Tony Frank in which Jane morphed into an androgynous, free-spirited tomboy, as highlighted by the ragged stone washed flares worn and her short, shaggy hair. A rag doll clutched to her chest being the only concealment of her breasts. The doll, at Birkin’s behest, was buried with Serge when he passed away in 1991.

Similarly in the 1976 film Je T’Aime Moi Non Plus, Gainsbourg directs a Birkin with masculine features who seduces a homosexual boy, played by Warhol Factory’s habituè Joe Dallesandro.

The song, joked Jane, “when I die, will be the tune they play as I’ll go out feet first”. It was the source of joy and torment of a career which also boasted a superb stint in the seventh art. From her beginnings in Antonioni’s Blow Up, to Jacques Deray’s La Piscine (1969) alongside Alain Delon, to her mature work under the direction of cinema greats such as Agnès Varda with whom in 1988 she collaborated in “Jane B. par Agnès V.” and Jean-Luc Godard in “Keep You Right Up”, 1987.

The song was the only French tune that the Jamaican musicians with whom Gainsbourg recorded his acclaimed and controversial 1979 reggae album “Aux Armes Et Caetera” knew when he flew to Kingston. On the album’s promotional tour, Jane followed Serge in an atmosphere of tension, political threats and unsettling phone calls triggered by the crooner’s upbeat remake of the Marseillaise.

One night, in Strasbourg, the theatre is picketed by paramilitaries, and the Rasta musicians don't want to hear no reasons about getting on stage, some say because Serge told them not to, some because they demanded extra money due to the distressing condition. Jane follows the scene from the side of the stage, entrenched behind the stacked amplifiers. Gainsbourg is by himself under the scorching spotlight. When he begins to sing the national anthem a cappella, the soldiers can do nothing but stand up and join in. The most peculiar of the theatres of the absurd.

As brilliantly absurd as the life that, now looking back, Jane seems to have lived, especially when compared to a present in which we do anything to avoid showing our true selves, all to snatch a seat in a jet-set that is no doubt an overcrowded bacchanalia of loud glamour and just as bare of icons, authentic ones.

Opening image: La Piscine (1969), film still