Born in Sardinia, Graziano Origa had taken his first steps in the art world as a cartoonist, the professional activity that defined his whole life.

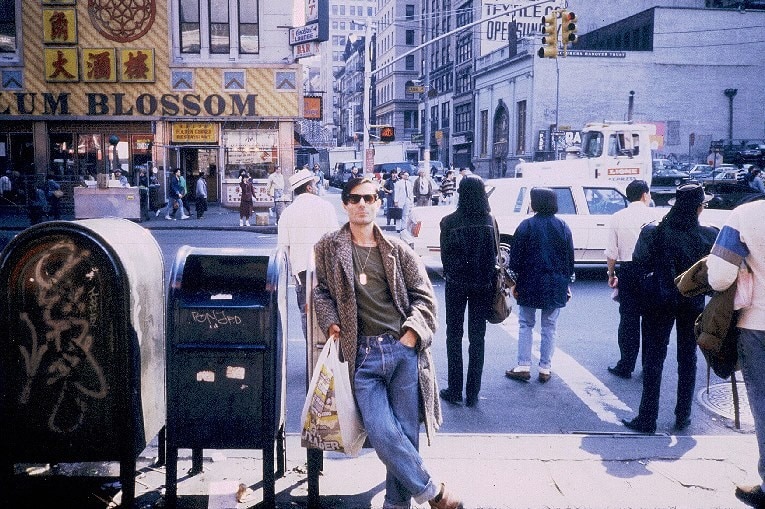

In between, a life spent between Milan and New York, two souls he had embodied between the late 1970s and mid-1980s. On the one hand, the city of Plastic, of Italian punk prime movers Enrico Ruggeri and his friends Krisma, Maurizio Arcieri and Christina Moser – who also recently passed away. On the other, the metropolis in which punk, street and pop art were coming together, under the influence of Keith Haring and Andy Warhol, whom Origa portrayed in his writings as "a face devoid of melanin, a canary body, a bald head, a grey cock and electric synthetic hair, who like his mother Julia still speaks in Czechoslovakian, daydreaming [...]".

Origa had synthesised these two artistic identities and schools of thought first in the magazine Gong, with its refined graphic identity, and from 1979 in his masterpiece, Punk Artist. Under the curator’s vision, graced by his surrealistic touch, the publication merged Warhol's Interview with the punk magazine Slash, pursuing an abrasive yet refined aesthetic, where the writings were accompanied by illustrations by Origa himself and photographs by Joe Zattere, the partner of a lifetime.

He recalled its genesis, pointing out how it had been Warhol himself to pitch him to supersede the Italian edition of Interview. “You give me $100 to use the logo, another $100 to put my name on it, $100 every time you take one of our pictures and $100 for every star I’ve interviewed. And I'll take you to McDonald’s tonight.”

“Well, you know what Andy? Let’s say I do it, but I call it Punk Artist, I use my name, my pictures and my interviews. And tonight I'll take you to the Sardinian restaurant on 54th, called Due Merli,” was Origa’s response.

He had defined the magazine as a “decadent, refined, trashy but elegant, sometimes anguished, sometimes upbeat periodical”. In a word, Origa had already envisioned the post-modern culture that would shortly follow.

After all, as the singer, songwriter and now esteemed painter Ivan Cattaneo points out, “Graziano was the Warhol of the Milano da Bere”, in years when – in the words of Italo-pop hero and long-standing friend Johnson Righeira – “Milan was perhaps even better than New York. [Club] Plastic was a true democracy: transvestites, models, fashion designers, drug dealers, everyone was on the same level once you went through the door selection, as long as you had a story to tell.”

As both of them affectionately recall, Origa and Warhol were similar in the physiognomy of their hollowed-out cheeks, their oversized transparent acetate glasses frame, and their language made up of “half sentences, punctuated and never finished”.

His Milanese home had been decorated by Keith Haring, you’d meet all sorts of personalities in there, from actress Eva Robin’s to fashion designer Sandro Pestelli, who back then had his boutique, Gerard, in front of Armani’s in Via Durini. As Johnson recalls, “in the bathroom he had urinals like in English clubs...I had only seen that in service stations in Italy, at the time”.

In 1980, the magazine-cum-art movement also became a film directed jointly with Zattere, Punk Artist The Movie, possibly the first in Italy to touch upon the subculture, while stylistically it nodded to splatter blood drips in the fashion of horror B-movies and to underground erotica. As Origa himself recalled, painting a veil of mythology around it, the only copy of the film was stolen immediately after the first screening, at the Primadonna discotheque in San Babila, making it lost forever today. Origa returned to cinema in the 1990s with “Kairos & Kronos”, alongside faces old and new of the Italian underground, including Tre Allegri Ragazzi Morti and Ivan Cattaneo, who also worked on the score.

Punk Art, the artistic current Origa claimed to have pioneered, was simply an aesthetic matter, but above all a philosophy, made up of exploration and continuous rupture with the status quo. Simply consider that by the time Punk Artist came to its second issue, in a lysergic interview interview with [post-punk/synth pop band] Krisma, everyone already declared their boredom and disillusion with this much-talked-about punk.

The same attitude led him to showcase his artworks at Plastic between 1978 and 1980, in a biennium in which the venue was defined by Origa as a “dandy temple”, and then to give life, with situationist flair and artistic liveliness, to magazines such as Gay Italia, Stallion, Blueboy, Torso, Fumetti d'Italia and Focus.

With Origa, we lose another pivotal protagonist of the European punk season, but above all a key figure in understanding its philosophy and iconography, highly respected in the comics industry – “the dark eminence of Italian comics”, Righeira dubs him – but still little celebrated for his wider artistic legacy. As Cattaneo comments, “at the time, [in Milan] on top of the discotheques, there was no physical space to meet and talk with each other without music, something like Warhol’s Factory...that always stood as one of the limits to his recognition in Italy”.

Opening image: Graziano Origa in New York, mid-1980s. Foto: Graziano Origa archive.