Masks to change appearance, mind-blowing gadgets, a lair encapsulated on the side of a mountain and mid-century villas, luxury cars, jewels, but also thrill and magnetic charm. All traits that for nearly sixty years have been giving to Diabolik an unparalleled appeal.

The character born out of the imagination of the Milanese Angela Giussani in 1962, has been able to impose himself as one of the most successful and longest-standing Italian comics of all time. For this reason, its cult status makes the new film directed by the Manetti Bros a much-awaited appointment.

Mario Bava’s design masterclass

Making Diabolik an all-Italian icon, though, is also its state of anonymity abroad, if only acclaimed B-movie hero Mario Bava hadn’t directed a cinematic transposition of his adventures in 1968. A motion picture where the King of Terror transformed into the King of Design in an ultrapop and visionary whirlwind of costumes, scenes and interiors.

The film was conceived in a fervid season for the dialogue between cinema and comics, with Pop Art being their common ground. If as early as 1963 Federico Fellini replaced dialogues with onomatopoeias in some parts of Marcello Mastroianni’s script for 8 1/2, it was Roger Vadim’s Barbarella (1966) to fully acknowledge the trend of comics on the big screen. Never mind the scripts nor its kaleidoscopic eroticism, it was the set and costume (Paco Rabanne) design what truly made the difference, paying off producer Dino De Laurentiis’ perseverance in retrieving from the rubbish bin the script his wife had thrown away. Comics were deemed as something not sufficiently high-browed for the seventh art, but little did she know.

Bava’s Danger: Diabolik was therefore born out of De Laurentiis’ will to replicate the box office success of Barbarella, this time with a made-in-Italy comic though. The result? An orgiastic, but not less sophisticated, triumph of plastic design and futuristic-looking costumes. Diabolik’s skin-tight black catsuit was in fact perfect to embody the love nurtured for PVC by the underground fashion and interior design industries of the times. In full Space Age ecstasy, both the catsuit and the anti-hero's characteristic black Jaguar E-Type were reproposed in a white variant suiting a Moon expedition. An act of freedom towards what, at first, might have seemed like an untouchable icon, that sums up the mind-blowing iconographic power of the film.

A country where, according to Eva Kant, “theft is a useless provocation”, and where Diabolik “would have no reason to exist”.

However, Bava’s true coup de theatre was the set design. As John Phillip Law – who in the film interpreted Diabolik – recalled on many occasions, when he first arrived on set, pretty much none of the scenes seen in the final edit were there. Once he had walked behind the camera lens, though, everything magically appeared. It was Bava’s undisputed ability in dilatating and deforming the space available through the use of framing, lens filters, and by overlapping photographs. Hence, sticking to the outrageously low budget given by De Laurentiis, the director was able to create the illusion – like cinema itself, after all – of space, giving life total environments in the style of Verner Panton’s.

Space Age design comics-style

Under the art direction of Flavio Mogherini (already a collaborator of Fellini), Enrico Michettoni crafted models for the interiors inspired by Nanda Vigo and Joe Colombo’s pieces. His Op Art-style creations balanced white plastic geometrical shapes with steel details and chronotropic surfaces. The interiors of Diabolik’s cave, where the bare rock of the mountain is the capsule to futuristic gadgets, are reminiscent of those created, in the same years, by for the pioneering animated puppets TV show Thunderbirds and for spy films that could instead count on lucullan budgets, like the James Bond franchise. On the other hand, inspector Ginko’s office is the aesthetic and moral counterpart of Diabolik’s lair, with its sober yet flawless interiors boasting modernist paintings and an Arco lamp by Castiglioni.

At the costumes, Luisa Marinucci and Giulio Coltellacci bring froward the experience matured on the set of The Tenth Victim (1966) by designing dresses and catsuits with neat and geometrical shapes, now characterised by sensual see-through patterns, now by vinyl or sparkling paillettes, keeping André Courrèges and Paco Rabanne as pivotal references. The jewels by Nino Lembo – a former actor turned accessory designer for cinema and television – bring on screen the opulent and sophisticated loots seen on the comic pages.

Talking of Italian elegance, we could not help but to mention the dreamlike music by Ennio Morricone, featuring psychedelic duo and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s collaborators Chetro & Co. The musicians also stepped on screen with a cameo in one of the most delirious and eye-pleasing scenes of the whole film: a party in an underground cave-like club where Bava employs PVC sheets and coloured filters to evoke the trippy and tribal experience of a hippy happening.

Diabolik the Pop icon

If Diabolik had brought glamour into a traditionally popular medium like comics, Bava went further by turning the black and white of the pages into an explosion of Pop colours. The contrasting use of yellow and black, for instance, highlights the film’s bond with the tradition of the Gialli Mondadori, budget Italian pulp novels typically associated with their yellow paperback covers. However, at the same time, it offers a new yè-yè and Lichtenstein-flavoured spin to them. Animated graphics, then, crown several scenes, one of which culminates with a representation of Twiggy’s face, the quintessential symbol of the cultural revolution of the Swinging London and of its impact on visual aesthetics.

As a matter of fact, Diabolik’s trademark silhouette logo drawn by illustrator Remo Berselli would soon acquire a life of its own, imposing itself into the Italian popular culture. By the mid-1960s Caterina Caselli’s backing band Gli Amici had adopted the logo on their drum, while many other Beat bands had integrated black masks or catsuits into their stage costumes.

Diabolik even made his way onto the iconography of football ultras, as well as on the pages of Domus, when in the mid-90s it was used for the ad campaign of blinders firm Croci. Not to mention the many K-lettered tribute and parody comics that followed, like Genius, Satanik, and Kriminal – which also tried to replicate, without much success, Diabolik’s cinema experience. Or, more recently the likes of Disney’s Paperinik (Donald Duck’s alter ego) and Cattivik.

Comics as a mirror of Italian costume

Diabolik’s flair represented something totally new for the status quo of the Italian – and not – comics of the times, and was no doubt rooted in Angela and Luciana Giussani’s sophisticated bourgeois taste. Their creation was able to give an intellectual spin to the violence and tension of pulp fictions. Without Diabolik we could hardly envision the Milanese erotic-pop style of Guido Crepax’s Valentia, another icon of 1960s Italian comics. Diabolik anticipated the psychological introspection of graphic novels, but still firmly maintaining the distance from the mannerism of American superheroes, or the aesthetic exaggerations of Mangas.

Diabolik didn’t simply embody the design of the times, but also the costume of a nation. In 1974, its pages gave voice to the campaign in support of the introduction of divorce in Italy, while on another occasion the King of Terror praised Mao’s China, by recognising its values of equality. A country where, according to Eva Kant, “theft is a useless provocation”, and where Diabolik “would have no reason to exist”. The Giussani sisters themselves stated, in an interview for newspaper Corriere della Sera, that Diabolik incarnates the evil own of capitalistic society.

Eva Kant herself, a woman as ruthless in her actions as profound in her feelings, introduced a new type of female anti-hero, a character that embodied the progressive emancipation of women in a society still asphyxiatingly paternalistic. An attitude that mirrored that of Angela Giussani, whose creation was first of all a cheeky challenge to his husband, owner of the publishing house Astoria. Diabolik’s publisher Astorina, in fact, stood as a provocation. A successful one, we may argue.

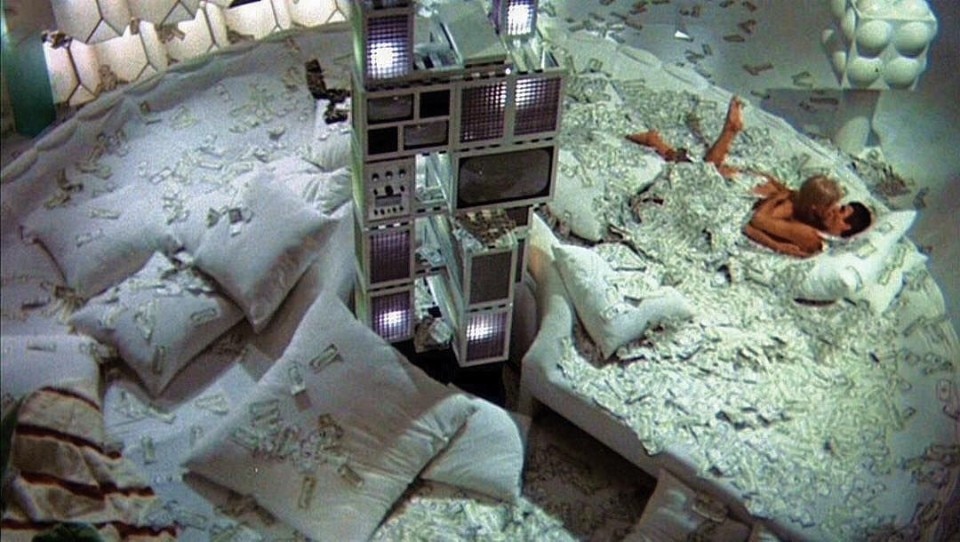

Diabolik made us fall in love with the anti-hero figure, reminding us that in life the border between virtue and sin isn’t as neat as comics and films had so far led us to believe. Even Ginko, the anti-anti-hero, can become the hero. That’s why we owe Diabolik. His criminality is devoted to the genius, to the sophisticated theft, and not to mere violence as displayed by the Eurocrime films of those days. Even when the loot is simply made of banknotes, we may close an eye or two, if they serve as a blanket to make love on a white rotating design bed.

Opening image: John Phillip Law and Marisa Mell as Diabolik and Eva Kant on the set of Danger: Diabolik, Mario Bava, 1968. Courtesy Pinterest

FADE Family is the new approach to outdoor living

The latest addition to the PLUST Collection is a line of furniture inspired by the texture of white stone, which illuminates as evening falls.

.jpg.foto.tbig.jpg)