It was 1983 when Domus dove deep into a New York that was in a state of flux: after the economic and social crisis of the 1970s, the city of the 1980s was to be the city of finance, business, rampant yuppism and its symbols. It was at the beginning of this decade that iconic places such as the Times Square we know today began to take shape, and the Chrysler Building was given the bright decor that had been planned for the 1920s but never realised. It was the beginning of a decade in which postmodernism entered its most theatrical phase, in which skyscrapers returned to Manhattan and the city, like them, became – in the words of César Pelli – a city of optimism, of celebration, of joy. And wealth, and power. “Tower of Power” would be the name given to Philip Johnson's AT&T, then nearing completion. And next to it, the mirrored and gilded glass of Trump Tower, the urban symbol of the tycoon who would later become President of the United States. The prologue to a historical phase that would continue to develop its ways and symbols for decades to come, with consequences that are now known to the entire planet. The portrait of the city of business and its new skyscrapers appeared on Domus in February 1983, issue 636.

What Domus said about Trump Tower in 1983, when it was still under construction

In the early 1980s Domus explored New York as finance, power and skyscrapers were swarming back to the city. In the tower Donald Trump wanted, the origin of a story that has come down to the present day could be read.

View Article details

- Fulvio Irace

- 06 November 2024

Certainly, “from the vantage point of 1982,” as Martin Mayer wrote in “The New York Times” on 31 October '82, in a triumphal advertisement dedicated to Manhattan's remarkable real estate boom, New York in the mid-'70s did seem to have reached a dramatically low ebb with no apparent way out. Like a chronically sick patient, the decayed heart of the old empire looked as if it might give way beneath the burden of its numerous diseases. Employment was falling by 15,000 jobs a year, the population was draining at the rate of 1.5%, industry was at a standstill and the big corporations were moving out to sunnier places in the south. The municipality was on the brink of bankruptcy.

As recently as 1975 the “big apple” was biologically beginning to wither. Whole districts were crumbling and being abandoned by the population at a dizzy rate. Urban disaffection and antisocial behaviour were rife. Entire buildings stood empty, awaiting improbable buyers. The crisis in the real estate market brought a sharp drop in rents and land values.

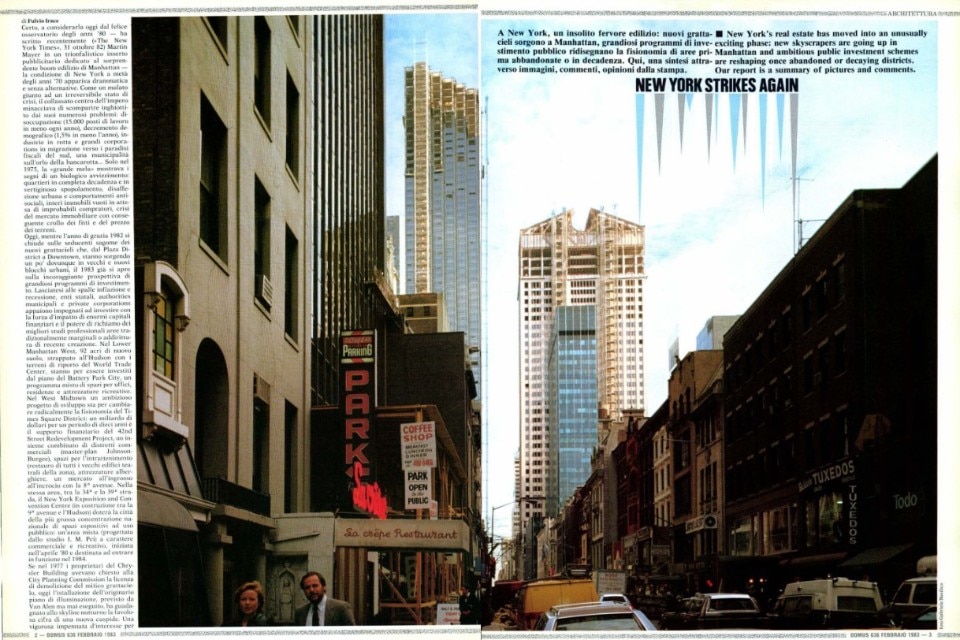

Today, as the year '82 mercifully closes, against the seductive silhouettes of the new skyscrapers that, from the Plaza District to Downtown, are rising everywhere among urban blocks new and old, 1983 has started out under the auspicious prospect of investment schemes on a grand scale. With inflation and recession behind them, government agencies, municipal authorities and private corporations are harnessing vast financial resources and the magnetic power of the best architectural partnerships to the development of traditionally marginal and even newly created areas.

In Lower Manhattan West, 92 acres of land, snatched from the Hudson using landfill from the World Trade Center, are about to be developed as the Battery Park City estate, in a combination of office, residential and recreational space. In West Midtown an ambitious development project will soon radically alter the face of the Times Square District. 1 billion $ are to be spent on the ten-year 42nd Street Redevelopment Project, which incorporates business districts (master-planned by Johnson-Burgee), entertainment (restoration of old theatres in the zone), hotel facilities and a wholesale mart in Eighth Avenue.

In the same area, between 34th and 39th Streets, the New York Exposition and Convention Center, under construction between 9th Avenue and the Hudson, will endow the city with the heaviest national concentration of exhibition space for public use, in a mixed area (designed by I.M. Pei & Partners) of business and recreation, begun in April 1980 and expected to start operating in '84. It was only in 1977 that the owners of the Chrysler Building were asking the City Planning Commission for a permit to demolish their mythical skyscraper.

Yet today the original illumination planned by Van Alen for the top of the building has added a fabulous new pinnacle to the nocturnal skyline. A keen burst of interest in the historic roots of an autochthonous culture has produced the twofold result of articulate restoration in many past buildings and the bold new shapes of much of New York's new building.

Today, as the year '82 mercifully closes, against the seductive silhouettes of the new skyscrapers that, from the Plaza District to Downtown, are rising everywhere among urban blocks new and old, 1983 has started out under the auspicious prospect of investment schemes on a grand scale.

The new generation of lively, sensational skyscrapers designed by America's top architects would seem to express an appreciation of the heyday of the roaring '20s. Considered even in the early 70s to be a pathetic wreck of the international style, the skyscraper as a useful form of building and visual landmark is enjoying a bright new season of success. Between Fifth Avenue and Madison Square, a cluster of three towers nearing completion is a tangible emblem of what Paul Goldberger has called “the shifting attitude of Americans toward business (...), toward the environment and toward their own history.”

The effect of solid permanence conveyed by the new IBM Building (Edward Larrabee Barnes), the search for differentiated, varied surface effects in the glass Trump Tower (Der Scutt), and the mocking, brazen historicism of Johnson and Burgee's AT&T, are only the more conspicuous symptoms of a new wave that has swept from New York to Chicago and down to Houston with the post-modernist Indian summer and is trying to subside into an updated (smart) “neoromanticism” pledged to “pleasure” and “flamboyance”! “There is a degree of emotion,” writes Goldberger, “even passion, involved in the making of skyscrapers today that has not been present since the 1920s.”

And the familiarity of those elegant art-déco inflexions seems to have punctually inspired the sinuous cadences of Chicago's North Western Terminal by Helmut Jhan, along with Cesar Pelli's reflecting squares for the Battery Park City's commercial towers or the cleverly ascending outlines of Johnson and Burgee's Transco Tower in Houston.

As Pelli, designer of the almost finished extension tower on New York's Moma, said recently: “We are now free to create a new generation of skyscrapers — optimistic, celebratory, joyful, public, accepting their roles as icons (...) in human scale on the street and in epic scale on the skyline.” The disenchanted and eager eclecticism of the new architectural developments seems to have perfectly embodied the demand for uniqueness and representative impact suggested by leading corporate image policies and spurred by the transformation of the city from industrial production centre to capital of the new communications society.

The advance of management and of soft technologies, the values of concentration in the international services market, and the ramification of an underground economy which brought about the city's commercial renaissance, are also accounting for its architectural revival.

Pelli's affirmation (that “skyscrapers are part of the postindustrial revolution. They’re the new factories — paper factories, filled up with picture phones, Xerox machines and computer display terminals”) endorses the new real estate entrepreneurs' unshakable motto that “good architecture is a sound economic investment.” As the soaring value of real estate and land and the incidence of construction costs once again make the search for high standards of architecture a competitive matter, technological faith and a spectacular theatricality are the indispensable ingredients of the new success formula.

On the American stage, Philip Johnson — eminence grise and enfant terrible of New York's professional elite — is once again ahead of the times and confidently riding the tiger of change. “The tower of power” — as The New York Times (15 Nov 82) in fact rechristened the controversial tripartite column of the AT&T — is an exemplary event in the new trend: dignity and solidity to express the awareness of being the world's most powerful company; classical solutions and lasting materials to allow the architect to confront the eternal questions of building. “The Seagram Building was the best of its era,” Mr Johnson is reported to say, “and this would be the best of today.”

Opening picture by Di DW labs Incorporated on Adobe Stock