It was 1942, when Domus invited the most relevant and innovative names in Italian architecture to send in the designs for an ideal house conceived for themselves: answers from Mollino, Banfi, Belgiojoso, Peressutti, a young Zanuso, a proto-Californian Bianchetti with Pea and many others would flock; but it was not just architecture that was being addressed: it was culture in its entirety being called upon to tell stories of houses. And there came Maria Vittoria Rossi or, with the nom de plume by which she would definitively become consecrated, Irene Brin. A sharp observer and caustic commentator, journalist, gallery owner together with her husband Gaspero Del Corso – who is credited with the discovery of Alberto Burri – Brin can be said to have shaped Italian culture in the years before and after the Second World War. She was a journalist, a war correspondent from then Yugoslavia, then a promoter of Italian fashion dawning on the international scene, then from 1950, when she met the legendary Diana Vreeland, she became the Rome editor for Harper's Bazaar, the first Italian fashion editor, in the modern sense. In her many wartime travels, she had pursued the ideal house and, with her husband – who had made some sketches of it – had even almost built one: the story was published on Domus 182, in February 1943.

The ideal home

In Rome, we have a real house: marble staircase, lift, eight built-in wardrobes, wooden floors, two entrances, independent radiator, fireplace: I have learnt to lock up the qualities, secret and profound for us, of the house, in these polite and boring eulogies, which I pronounce in a mechanical voice, for my tenants, since we were forced to rent it. In two years – we left Rome with the outbreak of the war – I have had many tenants, fat, thin, good-natured or even bad, a Knight of Honour and Devotion of the Order of Malta who left empty straw-clad flasks in all corners, three baronesses who were manic about skin care, a Finnish musician, Riccardo Grippa, and, for the moment, an ambassador, or almost. Of course, none of them can understand our house, and restore its value of invention, of conquest of tenderness, to the Tyrolean wardrobe we brought down from an alpine hut, disassembled into fifty-seven catalogued pieces, to the Tyrolean chest of drawers found in the cellars of a castle, in Naturno, to the pot-bellied canteries that an old admiral sold us for two hundred lire: and so even the large, polished, rational wardrobes, with their many drawers and small drawers, can explain anyone that they were built in a Slovenian sawmill, last winter, a sawmill full of sparks during the day and always threatened with fire, at night.

Thus, our flat in Bocca di Leone, where so many unknown people have eaten and slept – we meet a few grenadier officers, a few Nordic singers, a few Milanese industrialists who talk to us, knowledgeable and friendly, about our red-and-white-striped hemp curtains, or my beautiful kitchen cupboard, all made of glass – this flat has remained for us as if closed under a crystal bell, or covered in white linings. It is still ours, no one has taken it, and faithfully awaits (touch wood, soon) our return. But in the meantime, we furnished at least ten others: in Abruzzo, in Barisciano, I had three rooms to myself, and a wooden bathtub, dyed red, and vaguely Pompeian, on wheels, so that, immersed in hot water, I could turn here and there: we used white paint, for the dirty furniture, and then peasant women’s handkerchiefs, black, with flowers, for the tablecloth, drapery, upholstery. We stayed there for a month. In Ranziano, near Gorizia, a mistress of a decayed castle gave me a hideous little parlour in false mahogany: I put hats, scarves, necklaces, in the display cabinets, and then I went to live, on top of a blanket, under the great elm tree in the meadow. In Onigo, in the Veneto region, I stayed with Comisso's cook, Emma, a dark, jealous, bitter old woman: two rooms up, two rooms down, the chimney of the kitchen, the pitched roof, and the water dripping on the bed at every storm: we opened an umbrella, for the night, and during the day we settled by the fire.

In Spresiano I did things big: I went to the hotel (with stables, cinema, billiards, bus stop, a petrol station), I took two rooms, painted them, collected the beds in one, the armchairs and tables in the other, bought twenty metres of checked fabric, I covered cushions, deckchairs, mirror frames, worked for five days without catching my breath, on the sixth my husband arrived and, after admiring everything, announced that we were leaving the next day.

In Biglia I lived on a terrace, with Persian carpets and brocade cushions and a crazy old woman: it was the first days of April, the trees were blooming pink. In Skrjlievo (Croatia), I decorated the space around the well: everyone came to fetch water there, the chain screeched bitterly, and you could smell the water, green and thick. In Skoflica (Slovenia), with 35 degrees below zero, I had a brown and sad room, multiplied by a thousand by a black and blue striped screen: in Smarje (Slovenia), the Christmas tree was our only comfort, for three months, in tune with the stars of unmovable frost from the windows: three children dressed in rags and gold, passed through the streets singing, in the unknown language “We are the Three Kings...”. We had many other niches: but also, and finally, a house, built by us, by the sea, this summer: I believe we deserved it. Right at the edge of the old Yugoslavia, towards Sussak, and the shores were white and tawny, like lion skeletons, the waves quiet and shining, the bushes of laurel, rosemary, thyme: Mrs Bacic's large garden sloped down from the road to the beach, and the gardener's hut stood there in the middle, full of shovels and old irons, with two windows, a climbing rosebush, and many storerooms dug by the dead gardener, in the thick walls, to keep wine, bread, oil, smoking pipes.

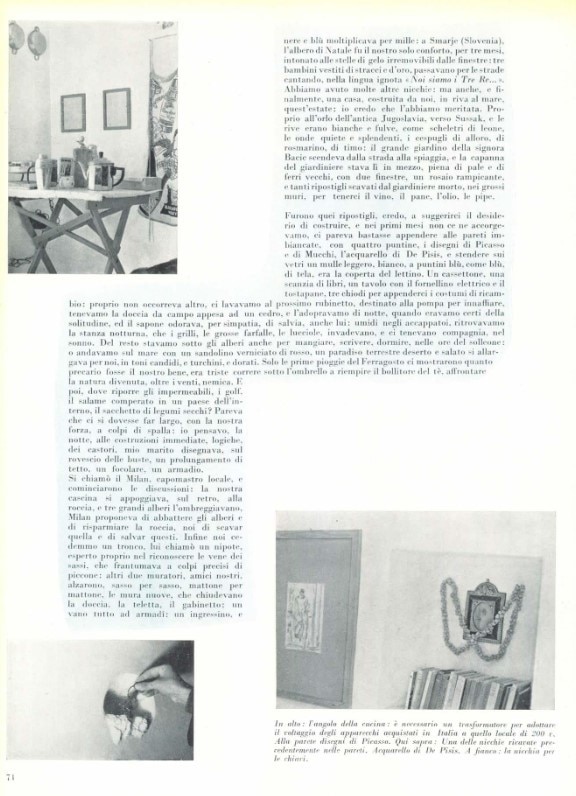

It was those closets, I think, that suggested to us the desire to build, and in the first months we didn't realise it, it seemed enough to us to hang Picasso’s and Mucchi’s drawings on the whitewashed walls with four pins, De Pisis’s watercolour, and to spread a light, white, blue-dotted mulle on the walls, just as blue, as the blanket covering the small bed was. A chest of drawers, a bookcase, a table with an electric cooker and toaster, three nails to hang spare costumes on: that's all we needed, we washed ourselves at the tap nearby, intended for the watering pump, we kept the camp shower hanging from a cedar tree, and we used it at night, when we were certain of solitude, and the soap smelled, out of sympathy, of sage, too: damp in our bathrobes, we would find the night room, which the crickets, the large butterflies, the fireflies, invaded, and kept us company, in our sleep.

After all, we also stayed under the trees to eat, write, sleep, in the hours of the scorching sun: or we went to the sea in a sandolin painted red, a deserted and salty earthly paradise spread out for us, in white, and turquoise, and golden tones. Only the first mid-August rains showed us how precarious our well-being was, it was sad to run under the umbrella to fill the tea kettle, to face the nature that had become, beyond the winds, an enemy. And then, where to store the mackintoshes, the jumpers, the salami bought in an inland village, the bag of dried pulses? It seemed that we had to make our way, with our strength, by shoulder blows: I thought, at night, of the immediate, logical constructions of beavers, my husband drew, on the back of the bags, an extension of a roof, a fireplace, a wardrobe.

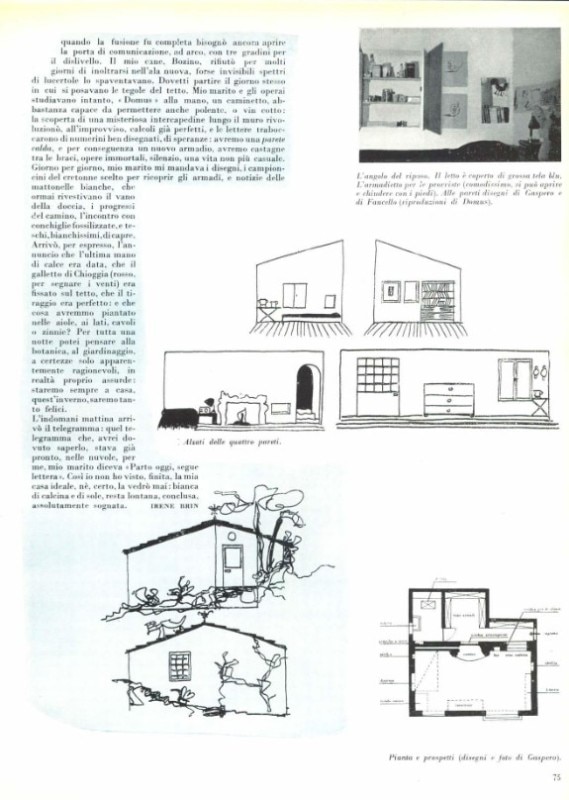

Milan, the local foreman, was called in and the discussions began: our little house was leaning against the rock at the back, and three large trees were shading it; Milan proposed to cut down the trees and spare the rock, and we proposed to dig the rock and save the trees. Finally we gave up one of them, he called in a nephew who was an expert in recognizing the veins in the stones, which he crushed with precise blows of the pickaxe: two other bricklayers, friends of ours, raised, stone by stone, brick by brick, the new walls, which enclosed the shower, the toilet, the lavatory; a room full of cupboards; a small entrance hall, and when the fusion was complete, we still had to open the arched doorway, with three steps to match the difference in height. My dog, Bozino, refused for many days to go into the new wing, perhaps invisible lizard ghosts frightened him.

I had to leave the same day the roof tiles were being laid. In the meantime, my husband and the workers were studying, Domus in hand, a fireplace, capable enough to even allow the cooking of polenta, or vin cotto: the discovery of a mysterious cavity along the wall suddenly revolutionized all calculations that were already perfect, and the letters overflowed with well-drawn little numbers, with hopes: we would have a warm wall, and consequently a new cupboard, we would have chestnuts in the embers, immortal works, silence, a life no longer casual. Day by day, my husband sent me drawings, samples of the cretonne chosen to cover the cupboards, and news of the white tiles that now lined the shower room, the progress of the chimney, the encounter with fossilized shells, and white goat skulls. There came, by express, the announcement that the last coat of lime was given, that the Chioggia cockerel (red, to mark the winds) was fixed on the roof, that the draught was perfect: and what would we plant in the flower beds, on the sides, cabbages or zinnias? For a whole night I could think about botany, about gardening, about certainties that were only apparently reasonable, in reality just absurd: we will always stay at home, this winter, we will be so happy.

The next morning the telegram arrived: that telegram which, I should have known, was already ready, in the clouds, for me, my husband said “I am leaving today, letter follows”. So I have not seen my ideal house finished, nor, I am sure, will I ever see it: white with limestone and sun, it remains far away, finished, absolutely dreamt of.