This article was published on Domus 756, January 1994.

Apartment building in the historic centre of Bale

Between reality and perception yawns an incommensurate gap, against which architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre De Meuron are fond of pitting their wits, investigating its many facets and redesigning them in their complexity. Superimposed on the manifold reality absorbed by a building is the dynamic of perception, primed by factors that are not only sensorial but mainly cultural and linked with memory. Time itself is called upon to be part of the project and enters into the process of continuous change undergone by cities. From this viewpoint architecture becomes the instrument of communication and a vehicle for comprehension of the contemporary. The strategies within which this approach can be given expression are, of course, bound to vary.

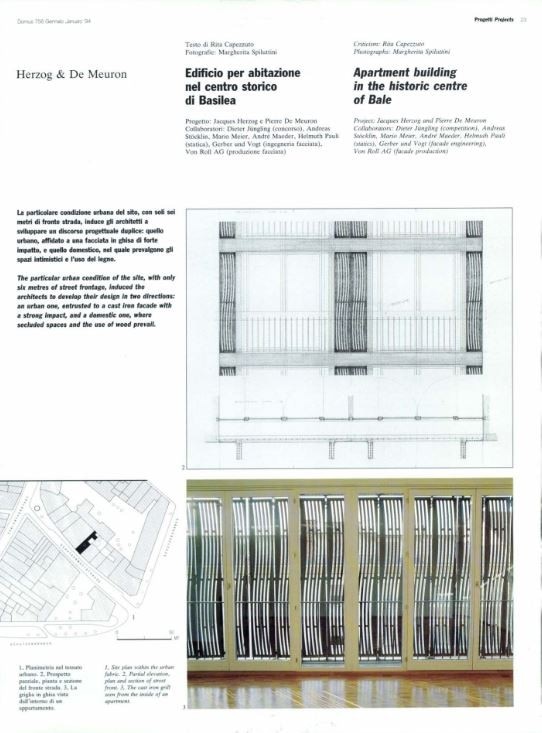

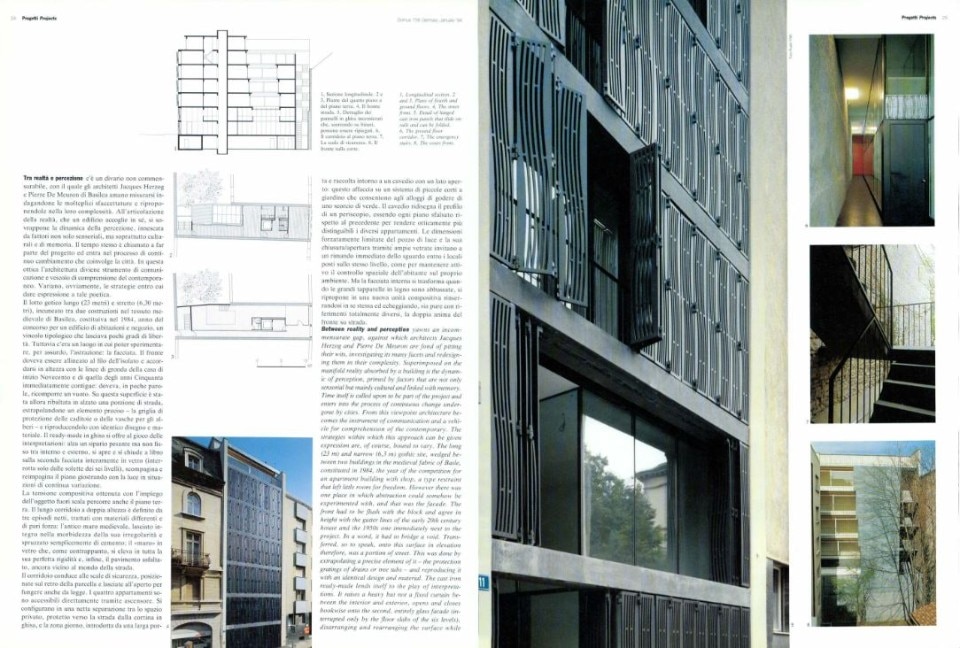

The long (23 m) and narrow (6,3 m) gothic site, wedged between two buildings in the medieval fabric of Basle, constituted in 1984, the year of the competition for an apartment building with shop, a type restraint that left little room for freedom. However there was one place in which abstraction could somehow be experimented with, and that was the facade. The front had to be flush with the block and agree in height with the gutter lines of the early 20th century house and the 1950s one immediately next to the project. In a word, it had to bridge a void. Transferred, so to speak, onto this surface in elevation therefore, was a portion of street. This was done by extrapolating a precise element of it - the protection gratings of drains or tree tubs - and reproducing it with an identical design and material. The cast iron ready-made lends itself to the play of interpretations. It raises a heavy but not a fixed curtain between the interior and exterior, opens and closes bookwise onto the second, entirely glass facade (interrupted only by the floor slabs of the six levels), disarranging and rearranging the surface while jousting with light in constantly varying situations.

The compositional tension created by the use of an out of scale object in this way also pervades the ground floor. The long, double-height corridor is defined by three distinct episodes which are treated with materials that are different but of equal force: the ancient medieval wall, left complete in the gentleness of its irregularity and simply sprayed with cement; the “wall” of glass which, as a counterpoint, rises in all its perfect rigidity; and, finally, the asphalted floor, which again comes close to the street world.

The corridor leads to the emergency stairs, located behind the plot and left uncovered so as to act as loggias. The four apartments are accessible directly by lift, configured in a distinct separation between private space, protected on the street side by the cast iron curtain, and the day zone. The latter is entered through a wide door and gathered around an atrium with one side opening onto a system of small garden courtyards. These enable each apartment to enjoy a glimpse of garden. The atrium redesigns the profile of periscope, each floor being staggered against the next in order to make the different apartments optically more distinguishable. The necessarily limited dimensions of the light well and its opening/closure by means of wide windows invite the eye to glance straight back into the rooms located on the same level, as if to keep the inhabitants in active spatial control of their private environments. But the inner facade is transformed when the large wooden blinds are lowered, recreating a new compositive unity by closing into itself and echoing, albeit with totally different references, the dual spirit of the street front.