“They only travel by Concorde / Doing things you can’t afford / They are the fashion pack / People you see in the magazines.” Just evoking Amanda Lear – in words and image – is enough to capture the collective meaning of the Concorde, and its unmistakable shape with delta wings and a “stork’s beak” ready to lower for takeoff and then break the sound barrier twice, connecting the world's major cities in a shrinking globe. In flight since 1976, after tests began in 1969, the Anglo-French aircraft associated its image with the idea of super- in every expression: it broke the sound barrier, the limits of flight altitude (the curvature of the Earth was perceptible from the windows), the state-of-the-art in engineering research, and not least, all limits of cost. In fact, no more than 20 were ever built – producing new ones from the late ‘70s became an insurmountable expense – the number of – narrow – seats never exceeded 100, and the tickets continued to have costs that made it, until the last flight on October 24, 2003, the ultimate expression of what was called the jet set in the 1950s.

In addition to spectacular feats of hedonistic years – celebrating three New Year’s Eves in three different parts of the world, for example – Concorde has been associated with prominent names in design from the beginning: such as Raymond Loewy, who designed the first interiors, or Andrée Putman, the French and international “design diva” – she too was a protagonist of the Parisian sociabilité of the Palace, alongside Saint Laurent, Lagerfeld, and Alaïa – who designed the final interiors, a total design work that Domus published in December 1995, in issue number 777.

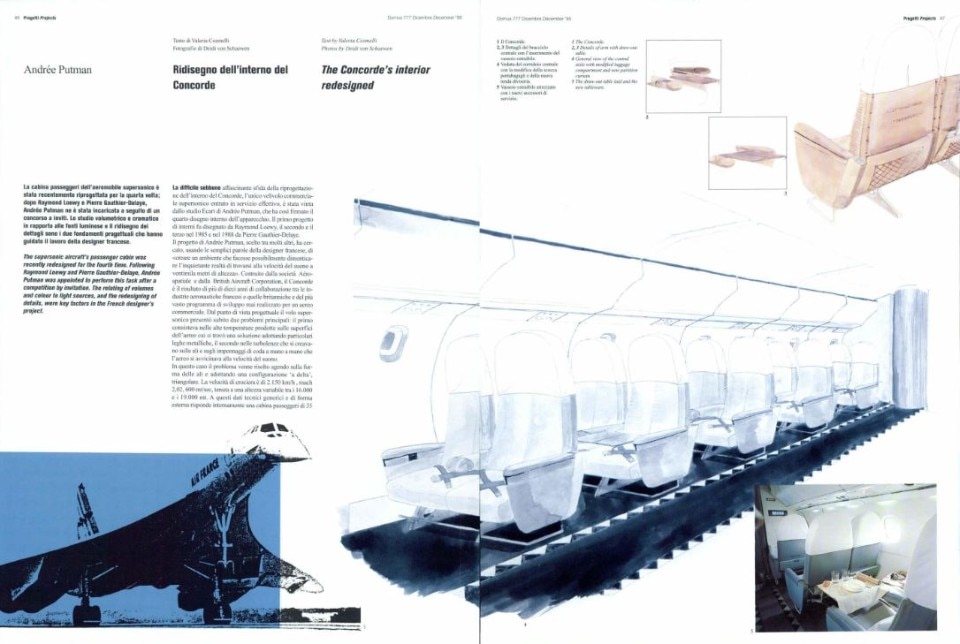

The Concorde’s interior redesigned

The difficult though fascinating brief of redesigning the interior of the Concorde, the only supersonic airliner to have gone into effective service, was won by Andrée Putnam’s firm Ecart. She thus became the fourth to design the Concorde’s fourth interior, the first having been done by Raymond Loewy, and the second and third, in 1985 and in 1988, by Pierre Gauthier-Delaye.

Andrée Putnam’s project, chosen from many others, set out – in the French designer’s own plain words – “to create an atmosphere that might help passengers to forget the uneasy feeling of flying at the speed of sound at an altitude of twenty thousand metres”. Built by Aérospatiale and the British Aircraft Corporation, the Concorde was the result of more than ten years of cooperation between the French and British aeronautical industries, and of the biggest development operation ever mounted for an airliner. From the engineering design point of view, supersonic flight immediately raised two problems. The first was that of the high temperatures produced on the surfaces of the aircraft, for which a solution was found by adopting special metal alloys; and the second was that of the turbulence created on the wings and on the tail unit as the aircraft approached the speed of sound.

In this case the matter was dealt with by acting on the shape of the wings and adopting a triangular, ‘delta’ configuration. Its cruising speed is 2,150 kph, mach 2.02, 600 mt/sec, at an altitude of between 16,000 and 19,000 metres. Internally matching these generic technical figures and external form is a passenger cabin with a length of 35 metres and a seating capacity of 100. The seat width including armrests is 54.2 cm and the longitudinal space available is 96.5 cm. This is – not only metaphorically – the narrow space within which Ms. Putnam’s project had to work.

Her choice was not to radically renew. Instead, her project concentrated on the retouching of a few details and on relations between volumes and light. Light becomes the guiding feature and key to the composition of space. The luggage rack body was redesigned to fit the form of the cabin and to form a vault, and it is opened by gripping its full length. Though just as capacious as the previous rack, it is now less bulky thanks to its new, gently curved design. A slight rise has allowed an indirect lighting system to be installed. With no more interruptions, this emphasizes and enlarges the scale of the cabin. The system is integrated by other light sources with different shades of colors according to the zones concerned: light pink near the door, tending towards grey in the technical spaces.

Another basic features of the project is its color scale, chosen with the evident intention of visually enlarging the cabin space and giving passengers a feeling of tranquility. The tones are sober and relaxing; the pearl white of the walls and ceiling, the brighter white of the headrests and cushions integrated by the grey and roseate beiges of the seat covers, of the cabin staff area partition curtains and of the moquette. The only contrasting colour, the blue of the Concorde trademark, sets off both the geometrical motifs of the moquette and the edges of the meal service tableware.

As has often happened in her eclectic career, the French designer has also redesigned and coordinated the graphics of the service signs and accessories, confirming the thesis that architecture is a discipline appointed not only to resolve the primary needs of human beings, but also to bestow harmony and balance on the settings of everyday living, however they may manifest themselves.

Opening image: British Airways Concorde G-Boac. Photo Eduard Marmet