Adriano Olivetti was born in April, 123 years ago. His life was short, abruptly and mysteriously cut short in February 1960 at the age of less than 60. He grew up in a Jewish household on his father’s side and in a Waldensian household on his mother’s side. He eventually converted to Catholicism. In just under thirty years, Olivetti managed to combine corporate profitability and community investment with an enlightened entrepreneurial vision rooted in the philosophies of authors such as Emmanuel Mounier, Jacques Maritain, and Simone Weil.

“I’ve never seen anyone wear that graygreen outfit with a pistol at the waist more awkwardly and less martially than him. He had a pronounced melancholic air about him, which was perhaps because he didn’t like being a soldier in the least. He was shy and quiet but when he did speak, he talked for a long time in a low voice and said confusing and enigmatic things while staring off into space with his small blue eyes, at once cold and dreamy.” This is how author Natalia Ginzburg described the young Olivetti during the First World War in her book Family Lexicon.

In 1932, under Adriano’s direction, the company founded by his father Camillo in Ivrea in 1908 developed its first portable mechanical typewriter, the MP1, based on a project by Riccardo Levi and designed by Aldo and Adriano Mangelli.

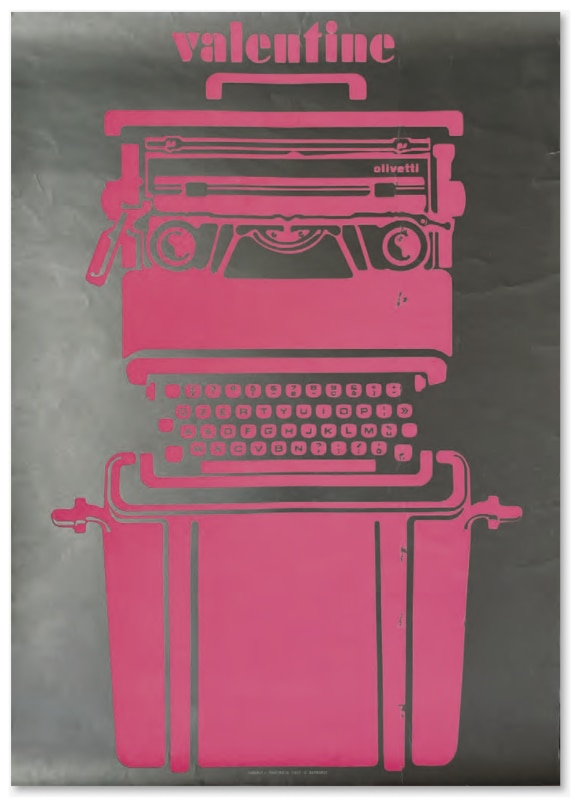

The tapered features of the body, especially in its red variation, seemed to anticipate the Olivetti to come, especially the iconic Valentine of 1969, designed by Ettore Sottsass Jr. and Perry A. King. At the time of Adriano’s death in 1960, Olivetti had already sown the seeds that would lead to its flourishing, guided by four cornerstones: functionality, innovation, aesthetics, and collaborations with creatives outside the agency.

Democratic design

Ironically, it was precisely after the death of its philosophical demiurge that Olivetti emerged over the next three decades as a global entrepreneurial phenomenon, embodying a harmonious convergence of technological, design, and social innovation.

But there’s more. During the postwar economic boom, Olivetti seized the opportunity to realize its vision of democratic design, rooted in English Art & Crafts and Calvinist ethics. Many Italian (and even international) companies, from Brionvega to Braun, would try to emulate this approach in the Sixties and Seventies.

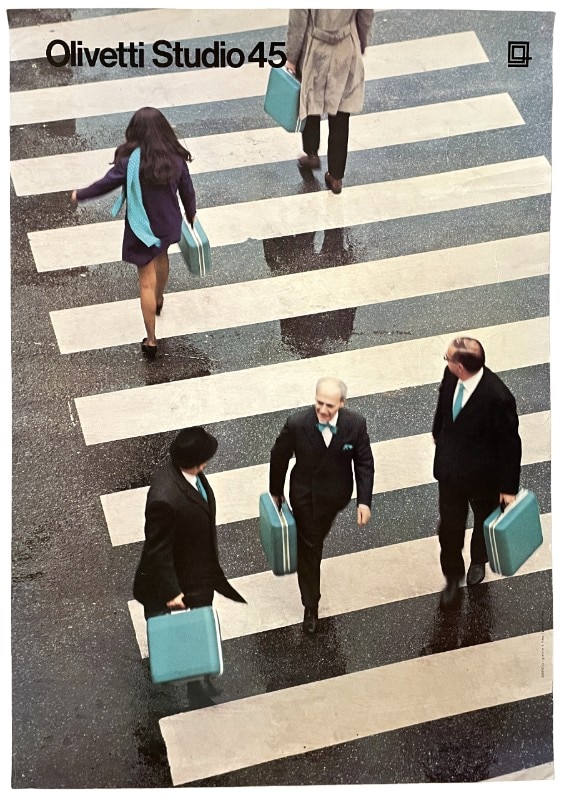

Olivetti succeeded like no other, evolving into a comprehensive brand that touched every aspect of daily life, seamlessly extending its conceptual and design capabilities from computing machines to a broader lifestyle context. The “Olivetti lifestyle” achieved an exquisite synthesis of form and function, combining the pragmatic demands of everyday tasks with pioneering design research. These were objects not only to be used, but also to be owned and experienced – accessible status symbols. Olivetti was undeniably desirable and coveted, yet profoundly democratic, from its theoretical underpinnings to its finished products.

Indeed, the cost of a Valentine typewriter, depending on accessories, ranged from 100,000 to 150,000 lire, approximately one-sixth to one-eighth of the price of a FIAT small car from the same period, such as the 850, which ranged between 600,000 and 800,000 lire. Today, this cost would be comparable to that of an Apple Mac, a company often seen as following in the footsteps of Olivetti’s vision.

Irreverent rigor

It mattered little whether the employee, the typist, the student, or the housewife knew that their typewriter had been designed by Ettore Sottsass Jr. or that their paperweight was an intuition of the poet Giorgio Soavi. Indeed, this only enhanced and elevated Olivetti’s mission. Good design became a necessary element for everyday life, rather than – as we might say today – merely a matter of hype and limited-edition collaborations for which people would queue at dawn outside a shop or speculate on resale.

Looking at the advertising campaign for Valentine, so swinging and yè-yè, with its photo-novel dynamic, one could easily mistake it for that of a clothing brand or a musical group. Whether today or yesterday, it evokes a desire to buy the object as a lifestyle piece, with its red plastic case and handle turning it into a designer, conceptual, and provocative bag. Another advertisement, also for Valentine, features a fuchsia silk-screen print on silver paper reminiscent of the chromatic experiments Mario Schifano used in the same years for the artwork of the cult album Dedicato a... by Le Stelle di Mario Schifano: a psychedelic complex, indeed.

“Perhaps the graphics we used to announce the Valentine weren’t perfect: perhaps they stray quite a bit from the old, famous, fabulous, classic cadence of Olivetti, but I hope the presumption – which certainly isn’t irreverence – will be forgiven for having tried to embrace new times and new structures of industry projects that face greater responsibilities and more conscious societies every day,” explained Sottsass to the Notizie Olivetti magazine.

From the office to homes: Olivetti objects and publishing

Throughout its history, Olivetti has always shown a certain irreverence in going beyond the industrial norms of its time, while at the same time preserving the Piedmontese and Waldensian rigor ingrained in its roots.

While the award-winning ADI typewriters and calculators have certainly left their mark, Olivetti’s legacy goes far beyond that. It boasts an extensive and eclectic catalog of projects that transcend mere materiality and touch various facets of Italian life, from the families of its employees to the entire nation. These include bags, records with modernist and optical covers, and exercises to improve typing skills. Above all, there’s the Olivetti Synthesis line of office furniture – a quintessentially Olivettian endeavor. From desks and chairs to ashtrays, pencil holders, letter racks, and telephones, this collection features designs by such luminaries as BBPR, Ettore Sottsass Jr, Alessandro Mendini, Bruno Munari, and Giorgio Soavi. The latter, a poet and writer, found a benefactor in Adriano Olivetti in the 1950s, who championed ambitious and forward-looking editorial ventures, including the founding of newspapers such as L’Espresso and Casabella.

In 1946, under the liberal and socialist banner of Olivetti’s bell symbol, Edizioni di Comunità was founded – a publishing house that is still active today. With the Second World War still raging, it envisioned cultural services as a cornerstone of Italy’s economic recovery. Alongside this was the Comunità magazine, which combined a strong focus on graphic design with articles of socio-political, economic and cultural significance. Edited by luminaries such as Carlo Argan, Alberto Moravia, Cesare Pavese, and Norberto Bobbio, it became a platform for thought-provoking discourse. Similarly, in Ivrea, the dissemination of culture permeated the entire community of Olivetti employees and their families. Through initiatives like the after-work club and the company library, culture thrived. The Olivetti Cultural Center hosted lectures by intellectuals, including Pier Paolo Pasolini on three occasions, while the company’s offices were decorated with works of art.

Beyond the factory: Olivetti architecture

The notion of community, fundamental to Olivetti’s philosophy, transcended the confines of the factory and the office. A pivotal moment came in the 1930s, when Adriano moved to Milan at the urging of his wife, Paola Levi, and met the architects Figini and Pollini. This meeting proved to be fundamental, sparking a philosophical and architectural epiphany that was seamlessly integrated into his entrepreneurial vision.

Olivetti, therefore, updates and expands the canons of that paternalistic entrepreneurship from the workers’ village which in 19th-century Europe had already brought Manchester to Italy, with the Lanificio Rossi in Schio, Vicenza, and the Villaggio Leumann in Collegno, Turin. Now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Olivetti’s social and civic architecture – from the West Residential Unit (commonly known as Talponia) designed by Gabetti and Isola to the East Residential Unit, also known as the former hotel with swimming pool and cinema La Serra by Cappai and Mainardis – represents the culmination of a democratic vision that goes beyond mere objects and corporate spaces, eschewing the capitalist obsession with brand omnipresence and monopoly in favor of community service.

The Olivetti legacy

Today, browsing through secondhand markets or searching for the keyword “Olivetti” on online shopping platforms, one encounters numerous artifacts that bear witness to Olivetti’s design legacy. Enchanted by the retro charm of the coordinated brand image, individual advertisements cut out of old magazines are sold at prices that often exceed those of the publications themselves. Typewriters have been transformed into home furnishings, though often with a cloying nostalgia favored by millennial wine bar decorators. The Synthesis line of ashtrays and pencil holders are now coveted for domestic use, looking visionary as never before, while the bags designed for typewriters and early personal computers are constantly reimagined on the street.

However we perceive and interpret the Olivetti artifacts of the past, these domestic legacies constitute an Italian socio-economic and design archaeology, embedded in the homes of former employees and customers. They serve as proof that Olivetti has permeated our daily lives, always with the harmony and grace of Maestro Manzi or a RAI television quiz, a guest at the domestic table, never an intruder.

Finally, the line of products for the Italia 90 World Cup seems to serve as a reminder. In retrospect, it symbolizes not only the swan song of the Ivrea company, which in the following decade would begin the painful process of fragmentation and dismantling, but also of Italy as a whole, which, with the Mani Pulite investigations, was moving towards the collapse of the First Republic, the promoter of the economic miracle to which Olivetti had contributed so much.

Opening image: Olivetti, Lettera 22. From: Olivetti. Storie da una collezione, di Polano S., Santero A., Ronzani Editore. Courtesy Olivetti

A Brutalist masterpiece frames the novelty signed 24Bottles

Giancarlo De Carlo's Collegi in Urbino is hosting a campaign for a signature product of 24Bottles: the brand's first titanium bottle, designed under the banner of essentiality.