1983. Ronald Reagan ruled in the United States, Margaret Thatcher in Great Britain, and Bettino Craxi in Italy. As the internet took its first breath and Motorola unveiled the first cell phone, Lucio Dalla captured the essence of the era in his song “1983”: “Ma qualcosa ci manca e quel qualcosa ci stanca / Ci stanca avere tutte queste cose che ci mancano se non le abbiamo più” (But something is missing, and that something tires us. We grow tired of having these things we miss once we no longer have them). These were the hedonistic years – a time marked by the need to find pleasure through consumption, and characterized by the euphoria over the abundance and accessibility of objects and possessions. Amidst this backdrop, Ettore Sottsass and the Memphis group emerged as pioneers, overturning conventions and forging new paths for design. It was an era where emotion and surprise held equal, if not greater, importance than functionality.

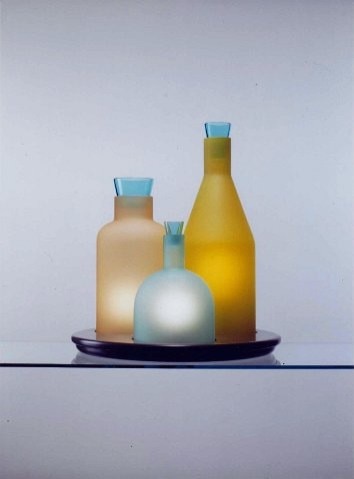

In the midst of this epochal era, Guido Rosati, a designer from Abruzzo, stood out with his remarkable creations. Known for his successful projects such as the Papillon armchair for Giovannetti and the Fatua lamp for FontanaArte, Rosati embarked on a new venture – the exquisite Bacco table lamp for ITre, a renowned Murano company. The Bacco lamp showcases a unique composition, featuring a metal tray with three compartments, each accommodating a bulb and a distinctive bottle-shaped white glass diffuser, adorned with blue glass stoppers. The ITre glasses are fashioned using ancient techniques such as soffiato, piastra, riporto, and incalmo. Thus, any variations in shape, color, or material composition should not be mistaken as imperfections but rather regarded as unique characterizations. The Bacco lamp’s trompe l’oeil effect is truly enchanting. At first glance, it appears to be a tray decorated with three elegant Murano glass bottles, but with a flick of the switch, the bottles transform into radiant light diffusers.

Bacco belongs to the esteemed category of Italian design objects that strive for polysemy and communicative versatility. While some objects from the 1960s, like Gae Aulenti’s Giova (1964), which serves as both a lamp and a flower stand, or Rimorchiatore (1967), a lamp, flower stand, and ashtray, embraced multifunctionality, Bacco takes a different approach. It remains monofunctional but never fails to surprise. This table lamp has an intriguing Magrittean quality – it appears to be one thing but is in fact another. It serves as an enigmatic symbol, perplexing and yet – quite literally – illuminating in nature. In the 1960s, multifunctionality was pursued through objects with complex and allusive forms. However, in the 1980s, the emphasis shifted to the element of surprise. Convenience, efficiency, and practicality took a back seat as wonder took center stage.

Bacco thus generates a profound perceptual hybridization and oscillation. Rosati is indeed renowned for his protean visions. Take, for example, the Fatua lamp, which resembles a jug, or the Papillon armchair, gracefully evoking the beauty of butterfly wings. Similarly, his Piego sofa bed introduced the innovative “ratchet” mechanism, offering a simple and practical way to transform the structure into a comfortable bed. The dynamic nature of the 1980s resonates within objects through mutations of forms, perceptual illusions, and functional transformations. This distinctive era helped alleviate the contrasting sensations of lack and satiety poetically portrayed in Lucio Dalla’s beautiful song.

A new world of Italian style

The result of an international joint venture, Nexion combines the values of Made in Italy with those of Indian manufacturing. A partnership from which the Lithic collection of ceramic surfaces was born.

.jpeg.foto.rmedium.jpg)