Subversive, provocative, elusive, tragic, grotesque, melancholic, and at the same time visionary. The figure of the fool has traversed the history of art and Western culture from the Middle Ages to Romanticism, yet it has been too little explored until now. This is the premise of the exhibition 'Figures du Fou: from the Middle Ages to the Romantics,' curated by Élisabeth Antoine-König, head of the Department of Decorative Arts, and Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, head of the Department of Sculptures. The project aims to fill this gap, providing the audience with the tools to explore the many facets of the representation of madness throughout the centuries. The exhibition, running until February 3, 2025, at the Hall Napoléon of the Musée du Louvre, reopens with the question: Fools are everywhere. But are the fools of yesterday like the fools of today? With a focus on French, Flemish, German, and English contexts, the exhibition presents 300 works, including paintings, engravings, tapestries, illuminated manuscripts, sculptures, and everyday objects. At the heart of the exhibition is Pierrot, dit Le Gilles (1719), an emblematic work from the Louvre’s permanent collection that has been recently restored.

You still have a month to visit the foolest exhibition around

300 works from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, gathered from around the world, on display in Paris until February 3, 2025, to answer a single question: Are the fools of yesterday like those of today?

© The Phoebus Foundation.

© National Library of France.

© Museum Koekkoek Haus Kleve, Photo A. Gossens.

© Yale University Art Gallery.

© Münchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Angewandte Kunst_photo G. Adler, E. Jank

© Bibliothèque nationale de France

© RMN-Grand Palais (Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille) Stéphane Maréchalle

© Museo Nacional del Prado, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn, image courtesy of Prado

© Meadows Museum, SMU photo Robert LaPrelle

© Warsaw, Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie / Piotr Ligier

© CC BY 4.0 NasjonalmuseetJarre, Anne Hansteen

View Article details

- Giorgia Aprosio

- 02 January 2025

The Medieval Fool: Transgression at the Margins

In the Middle Ages, the figure of the fool was closely linked to religious and moral issues. A symbol of the 'godless,' the fool lived on the margins of society, defying divine and social order. His condition was considered contagious, especially when love and passion were involved—two overwhelming and uncontrollable forces. Just as in epic cycles, Arthurian and Carolingian legends, where protagonists far removed from the codes of courtly love were swept into a vortex of desire, lust, and perdition. Socially defined by his difference, the fool rejects and at the same time fascinates, soon taking on not only the role of a moral symbol but also a specific social function. With his bells, striped cloak, and cap, the jester enters the court and becomes the indispensable counterpart to royal power: a satirical and subversive character, the only one allowed to question authority.

The Flemish: Between Satire and Surrealism

A fundamental chapter of the exhibition is obviously dedicated to the Flemish tradition, which interpreted the figure of the fool as a mirror of human contradictions, often with an ironic and visionary approach. Among the masterpieces on display are the famous Flemish Proverbs (1607) by Pieter Bruegel, a visual encyclopedia of the everyday follies of extraordinary complexity, translating popular sayings and proverbs into surreal and satirical images. Similarly, Concert in an Egg (1561) by Hieronymus Bosch immerses the viewer in an absurd atmosphere: a group of eccentric characters is engaged in a concert with their limbs submerged inside a gigantic egg. Not far away,The Conjurer (1525), attributed to a pupil of Bosch, stages a scam orchestrated by an illusionist, suggesting the subtle boundary between deception and truth.

From the Fool to Romanticism: The Modern Fool

The figure of the fool does not disappear even with the Enlightenment; on the contrary, it evolves, becoming a mask, like those from the Commedia dell’Arte – particularly Pulcinella – or Cervantes' Don Quixote. It is with Romanticism that the fool is definitively reinterpreted in light of new discoveries about the psyche and the growing interest in the unconscious. Madness becomes a lens to explore the psychoses of modern life, with particular attention to socially oppressed figures. A striking example in the exhibition is the work The French psychiatrist Philippe Pinel frees the mad from their chains at the Salpêtrière asylum in Paris in 1795 (1876) by Tony Robert-Fleury, set in a female institution, placed next to the portrait of Lady Macbeth by Charles Louis Müller (1849), where the woman clutches her shoulders and rubs her hands, gazing languidly at the viewer, caught between guilt and despair.

The fool and the artist: a deep connection

To those who break social codes, embodying the excesses and contradictions of society, everything is permitted, and the same applies to representation. The fool is not only an anthropologically and iconographically interesting symbol for the artist, but also a tool to bypass censorship and gain expressive freedom by portraying what would otherwise be unrepresentable. The connection between the fool and the artist reflects a symbolic solidarity: both figures of disruption, capable of stimulating new visions and interpretations of the world, have used each other for centuries, whether to exist on the canvas or communicate their message. "Figures du Fou" not only offers a look at the representation of madness in art, but also invites a rediscovery of it as a mirror of the tensions and contradictions of contemporary society. A universal theme that, through this exhibition, confirms its relevance today.

Exhibition: Figures du Fou: du Moyen-Âge aux Romantiques. Where: Musée du Louvre, Paris. Dates: From October 16, 2024, to February 3, 2025.

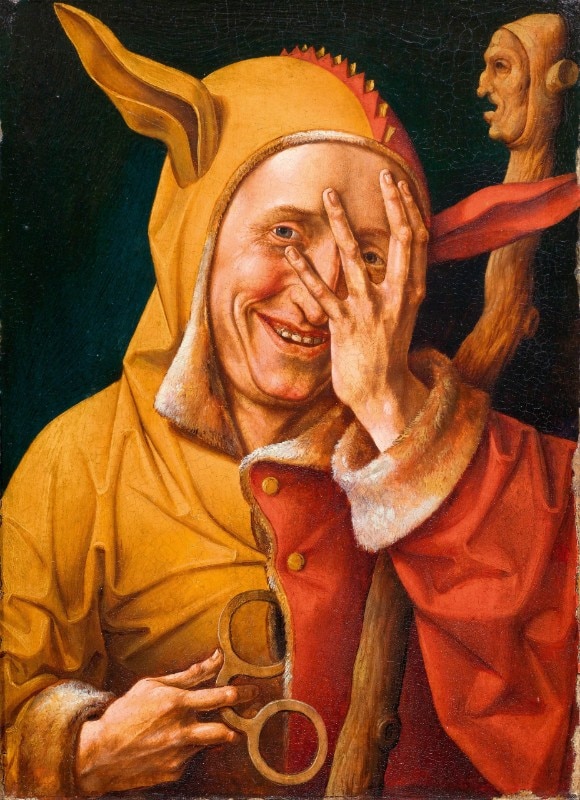

Master of 1537, Portrait of a Fool Looking Through His Fingers. Early Netherlands, around 1548. Oil on wood, H. 48.4 cm; W. 39.6 cm. Antwerp, The Phoebus Foundation.

Master E.S., The Fool and the Naked Woman with a Mirror. Upper Rhine, circa 1465. Copper engravings with burin, H. 148 mm; W. 108 mm (sheet). Paris, National Library of France, Department of Prints and Photography, RESERVE EA-40-BOX ECU

Arnt van Tricht, Towel Holder: Fool Embracing a Woman. Middle Rhine, circa 1535. Polychrome oak, H. 44.3 cm; W. 46.8 cm; D. 30 cm. Kleve, Museum Kurhaus Kleve – Ewald Mataré Collection, inv. 1980-04-02

Marx Reichlich, Portrait of a Fool. Tyrol, circa 1519-1520. Tempera on wood, H. 44.5 cm; W. 33.7 cm. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Bequest of Dr. Herbert and Monika Schaefer, inv. 2020.37.6

Dancers of Moresca (here: The Magician). Copies by Joseph Baumgartner, 1957-1958, after the originals by Erasmus Grasser (as shown here), circa 1480 (polychromy from 1928). Limewood, H. from 61.5 to 81.5 cm (depending on the dancers). Munich, Münchner Stadtmuseum, inv. K-lc 225

After Jean de Gourmont, O caput elleboro dignum, circa 1590. Hand-colored print; H. 360 mm; W. 490 mm (drawing); H. 425 mm; W. 555 mm (sheet). Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Department of Maps and Plans, GE DD-2987 (64 RES)

After Hyeronimus Bosch, Concert in an Egg. Early Netherlands, mid-16th century. Oil on canvas, H. 108.5 cm; W. 126.5 cm. Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts, inv. P.8.

Hyeronimus Bosch, Excision of the Stone of Madness. Bois-le-Duc, circa 1501-1505. Oil on oak panel, H. 48.5 cm; W. 34.5 cm. Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, inv. P002056.

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes, The Madhouse, 1794. Oil on tin, H. 43 cm; W. 32 cm. Dallas (Texas), Meadows Museum, Southern Methodist University, Algur H. Meadows Collection, inv. MM. 67.01.

Jan Matejko, Stanczyk at a Ball After the Loss of Smolensk, Kraków, 1862. Oil on canvas, H. 88 cm; W. 120 cm. Warsaw, National Museum in Warsaw, inv. MP 433 MNW.

Gustave Courbet, Portrait of the Artist Known as The Madman of Fear, circa 1844-1848. Oil on canvas mounted on panel, H. 60.5 cm; W. 50 cm. Oslo, The National Museum, inv. NG.M.02169.