For the eighth time in its history, the territory of the Principality of Monaco has been reshaped and extended, thanks to its newest district reclaimed from the sea: Mareterra. Developed over a decade, the district evenly split between three hectares of private and three hectares of public pedestrian areas. Esteemed architectural firms, including Renzo Piano Building Workshop, Valode & Pistre Architectes, Foster + Partners, Stefano Boeri Architetti, and Tadao Ando, collaborated on designing the new structures built on this innovative land reclamation project. The landscape plan, with a strong focus on biodiversity, was designed by Michel Desvigne firm.

A two-kilometers-by-one strip of land, nestled between the mountains and one of the Mediterranean’s most stunning gulfs, Monte Carlo reflects the challenges and paradoxes of balancing the preservation of its precious territory with the scarcity of land for real estate development. With its limited extension and with a density of 18,600 residents per square kilometer, Monaco is the most densely populated state in the world. In recent years, the influx of residents – mostly attracted by favorable tax policies and Monte Carlo’s aura of exclusivity – has necessitated bold engineering solutions to make sustainable growth achievable through engineering.

“The greatness of a country is not measured by its size but by its ambition,” said Prince Albert II of Monaco during his inaugural speech for Mareterra. His long-term vision builds on initiatives from previous reigns, with the Principality pioneering the creation of artificial land reclaimed from the sea. Between 1907 and 1920, Monaco built three new ports – Fontvieille 1, Hercules Port 1, and Hercules Port 2 – along its coastline. From 1966 to 1973, the ambitious 23-hectare Fontvieille 2 district was completed, adding residential and commercial spaces to the city. This was followed by the 15-hectare Larvotto 2 project. Mareterra marks the culmination of these waterfront reshaping efforts. With its six hectares of newly reclaimed land, Mareterra is likely Monaco’s final expansion into the sea, as the authorities noted during the project's inauguration, due to increasingly stringent environmental and urban planning constraints that effectively halt further waterfront development.

Sustainability has been a central theme throughout Mareterra’s development, particularly regarding marine biodiversity. And URBAMER, the Monegasque agency overseeing the project, made it indeed a binding principle – apart from the undeniably impressive construction on the seabed, preserving the natural coastal ecosystem was a priority wherever possible. In the early stages of the project, it was the environmental impact studies, in particular those focusing on sea currents and seabed depths, which determined the design of the new coastal profile. To protect the presence and characteristics of the native flora, the Posidonia seagrass, along with other vegetation, was transplanted to other locations. Eighteen concrete caissons, built in Marseille, were later anchored to the seabed to form a foundation for the new artificial land. This foundation was filled and compacted with 27,000 tons of rock and 750,000 tons of sand sourced from France and Sicily. Before the bight was drained, fish were relocated to prevent die-offs, while the Larvotto and Spélugues marine reserves were protected through the use of anti-turbidity screens and adjusted dredging schedules to minimize sediment spread. The caissons were then manually scraped to encourage algae growth – a crucial first step in rebuilding a marine ecosystem conducive to life.

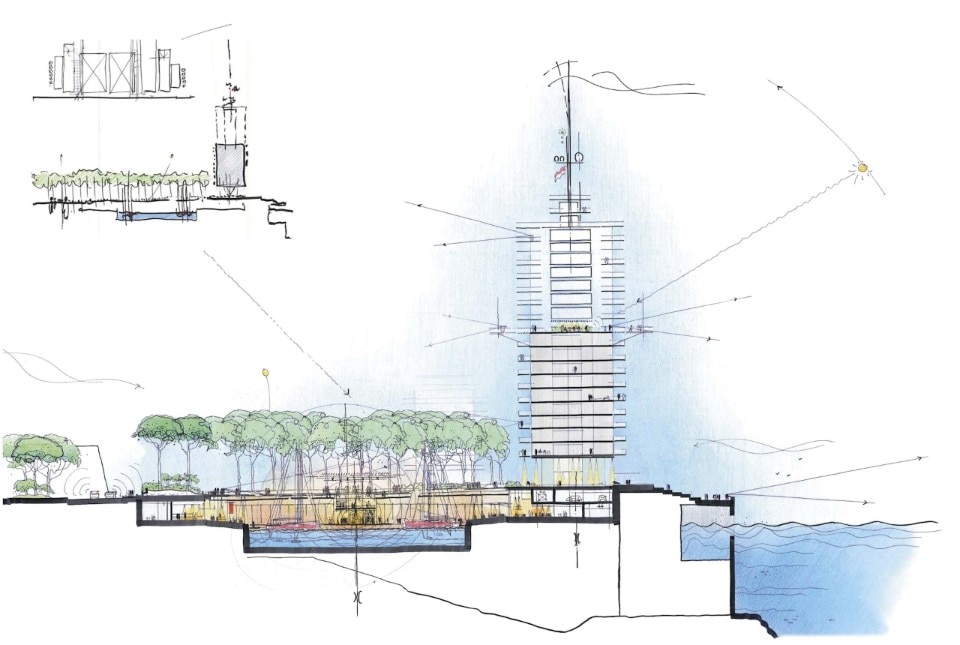

On this newly reclaimed land stands Le Renzo, a building that rises on the public promenade of the pier, evoking the design and materials of naval architecture. Its name, as one might guess, pays homage to its creators, Renzo Piano Building Workshop. Elevated on pilotis and clad in white marine aluminum, the structure acts as a visual filter, blending the horizon of the sea with the backdrop of the mountains. The façade, punctuated by balconies facing the horizon, achieves a particularly harmonious design with the inclusion of vertical balancing bars. Joost Moolhuijzen and Erik Volz of the Renzo Piano Building Workshop explained to Domus: “With Le Renzo, we partially obstructed the view from the old waterfront, so our goal was to restore it. That’s why we elevated the building, allowing the horizon to remain visible. However, reducing the idea of the building to a simple ship reference would be too limiting – the concept goes beyond it. It’s about capturing and bringing light to the space in a soft and natural way, creating a welcoming and generous environment accessible to the public.”

Sustainability has been a central theme throughout Mareterra’s development, particularly regarding marine biodiversity.

From Le Renzo, a public promenade extends along the new embankment, delimitating and integrating other buildings within lush Mediterranean vegetation. These structures, erected on an artificial embankment and surrounded by 1,500 tall trees from nurseries in the province of Pistoia, include those by Valode & Pistre, along with villas designed by Norman Foster, Stefano Boeri, and Tadao Ando. Facing the sea like the early 20th-century villas of the legendary French Riviera – la Côte d’Azur – these buildings enjoy an intimate and peaceful connection with nature, a stark contrast to the densely packed towers and mansions of Monte Carlo’s older developments of the past decades, built one on top of the other and often lacking in architectural distinction.

The general master plan was designed by Valode & Pistre, while the landscaping is the work of Michel Desvigne. Continuity with coastal vegetation was a key feature of his approach. Eschewing the Provencal aesthetic and exotic gardens typical of the Côte d’Azur and far from Mannerism, Desvigne’s language aimed to “guarantee the integration of a natural system within an artificial context. To make this possible, the creation of fertile soil was essential, and important for climate adaptation. The 30,000 cubic meters of soil used for Mareterra form the foundation for recreating the biodiversity and moisture characteristic of a Mediterranean ecosystem.” This new park is intended – according to the commissioner Anse du Portier – to benefit all citizens of the Principality. In a region where green spaces are scarce, the addition of this hectare constitutes a pedestrian path accessible to all, meandering through trees and shrubs and fleeing the logics of private gardens of gated communities, which prioritize the privacy of privileged communities.

Reducing the idea of the building to a simple ship reference would be too limiting – the concept goes beyond it. It’s about capturing and bringing light to the space in a soft and natural way, creating a welcoming and generous environment accessible to the public.

Joost Moolhuijzen and Erik Volz, Renzo Piano Building Workshop

The Mareterra project also serves as a significant promotional tool for the Principality. It demonstrates, as the Minister of Public Works, the Environment, and Urban Development Céline Caron-Dagion stated: “we can build on water in a viable, economically and environmentally sustainable way,” leaving this case study as a legacy for future coastal expansion projects. Beyond its technical and ecological achievements, Mareterra carries substantial economic significance. The project includes 110 apartments, 10 villas, and 4 townhouses, spanning three hectares of private space. Alongside the expansion of the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco’s convention center, these developments promise to invigorate the local economy and generate substantial revenue through VAT on property sales, set at 20% of the purchase price. Given the reported prices of Mareterra’s residence – ranging from €100,000 to €120,000 per square meter, approximately double the average cost in Monte Carlo, which already ranks as the world’s most expensive real estate – the financial impact will be far from negligible.