Who knows what will happen to all the gas stations when people will only need an electric outlet to fill up their car. We are immediately hit with preventive nostalgia. In Domus’s first year of activity, Gio Ponti wrote The Style of Gas, (Domus 11, November 1928) which focused on the new phenomenon of the new “Flash” refueling facilities that had started to appear in the urban landscape of the Italian Po valley. Then, when Fiume was added to the Italy in 1924, the country gained its first refinery, the Romsa, which in 1926 became the propriety of Agip, Azienda Generale Italiana Petroli (General Italian Oil Company). While the term “Fordism” hadn’t been coined yet and Tazio Nuvolari was creating his first racing stable, Ponti was fascinated by those white pavilions, “simple, cement, white, with large overhanging eaves covering the cars: decorated only with sports advertisement calls.”

Sprouting from there, he saw a modernity that would have changed architecture entirely, right there in those thin columns where Humber and Delage filled up their tanks, outrageously compared to Le Corbusier, the Greek temples of Paestum and the Parthenon in Vers une architecture (Toward an Architecture, trad. by Frederick Etchells) five years before: “The motor-car is an object with a simple function (to travel) and complicated aims (comfort, resistance, appearance), which has forced on big industry the absolute necessity of standardization […] Here we have the birth of style, that is to say the attainment, universally recognized, of a state of perfection universally felt.”

View gallery

View gallery

Studio di architettura e urbanistica Marco Petreschi, electronic dispenser. From Domus 621, October 1981

Giò Ponti, Illusività dell’architettura. Presentation of Oscar Niemeyer’s Clube dos Quinhentos. The service station is mentioned amongst the club’s several structures. From Domus 277, December 1952

Bruno Cassetti, Max Chelli, Marco De Michelis, Maurizio di Puolo, Marco Fano, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

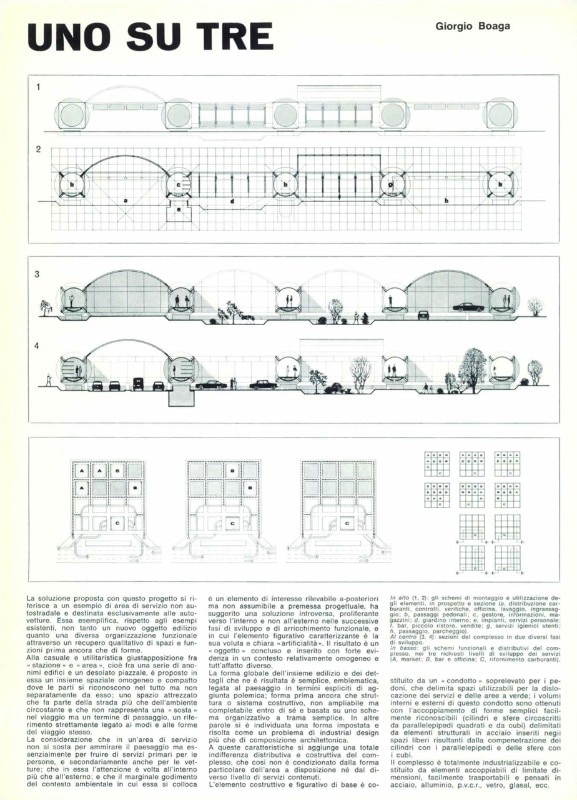

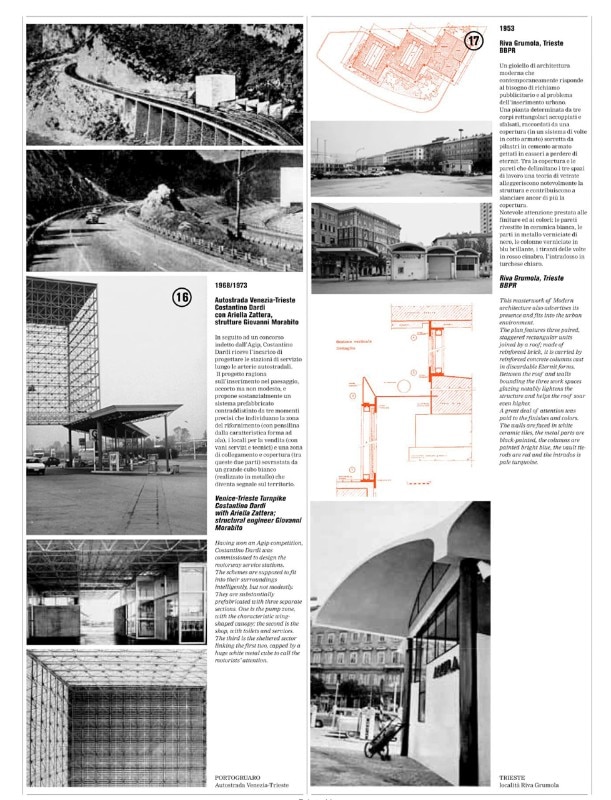

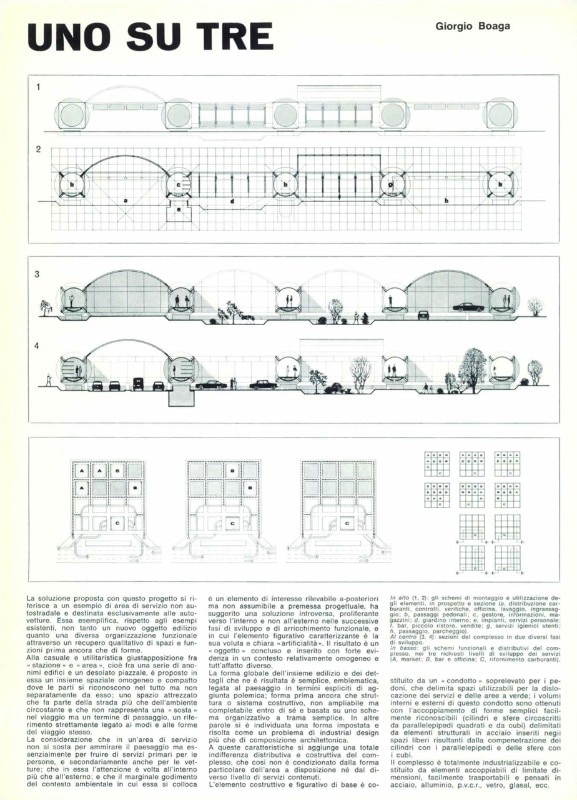

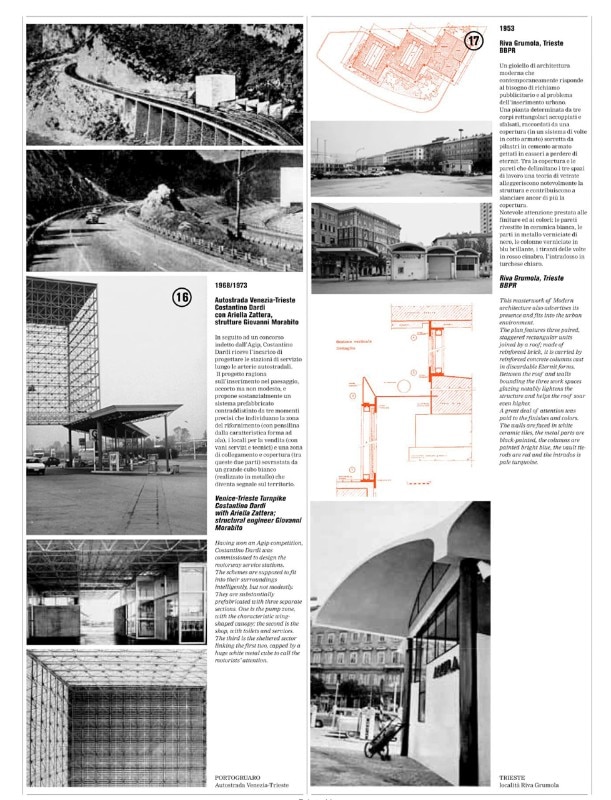

Giorgio Boaga, “Uno su tre”, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Mario Dal Mas, Manfredi Greco, “Scocca 70”, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Studio di architettura e urbanistica Marco Petreschi, electronic dispenser. From Domus 621, October 1981

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Minale Tattersfield & Acton, moveable filling stations, 1997. From Domus 797, October 1997

Giuseppe Terragni, projected standardized filling station, ca. 1940. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Camille Walala, Walala Pump & go gas station, Fort Smith, Arkansas, 2020. From Domus 1043, February 2020

Samyn and Partners, TOTALFINAELF service station and restaurant, Hellebecq, Belgium, 1999. Photo © Marie-Françoise Plissart

Samyn and Partners, TOTALFINAELF service station and restaurant, Hellebecq, Belgium, 1999. Photo © Marie-Françoise Plissart

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Studio di architettura e urbanistica Marco Petreschi, electronic dispenser. From Domus 621, October 1981

Giò Ponti, Illusività dell’architettura. Presentation of Oscar Niemeyer’s Clube dos Quinhentos. The service station is mentioned amongst the club’s several structures. From Domus 277, December 1952

Bruno Cassetti, Max Chelli, Marco De Michelis, Maurizio di Puolo, Marco Fano, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Giorgio Boaga, “Uno su tre”, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Mario Dal Mas, Manfredi Greco, “Scocca 70”, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Studio di architettura e urbanistica Marco Petreschi, electronic dispenser. From Domus 621, October 1981

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Minale Tattersfield & Acton, moveable filling stations, 1997. From Domus 797, October 1997

Giuseppe Terragni, projected standardized filling station, ca. 1940. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Camille Walala, Walala Pump & go gas station, Fort Smith, Arkansas, 2020. From Domus 1043, February 2020

Samyn and Partners, TOTALFINAELF service station and restaurant, Hellebecq, Belgium, 1999. Photo © Marie-Françoise Plissart

Samyn and Partners, TOTALFINAELF service station and restaurant, Hellebecq, Belgium, 1999. Photo © Marie-Françoise Plissart

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

So here is the style of gas, placed in parallel with the architectural styles even if the latter refuse to be called styles starting from Modernism, which focused only on the function and the social impact, never on the aesthetics.

However, going through the refueling facilities in chronological order is quite fun: to each decade corresponds either a style, a distinctive trait, or at least a Zeitgeist. From the 1920s machinisme to the 1930s sinuous shapes, like those in Klampenborg, Danmark, where in 1937 Arne Jacobsen designs a big, flat and perfectly round umbrella, and of the Fiat Tagliero gas station in Asmara, Eritrea, by Giuseppe Pettazzi, designed in a deco-like style and became part of the UNESCO World Heritage in 2017.

World War II marks a break even in this field, but then national reconstruction and the new Affluent Society of the post-war period became the driving force of small infrastructures which were an opportunity for a renewal of the imaginary: the Pavesi rest stop that Angelo Bianchetti built in 1958 on the Milano-Laghi highway was a big leap towards the future, and so was the Mottagril rest stop in Cantagallo, on the A1 Highway, by Melchiorre Bega built in 1960, the crowning achievement of the great endeavor of the Italian economic boom and result of the Eni-Autostrade-Fiat-Pirelli quadrumvirate.

Even pioneers were forced to face this topic, starting with Frank Lloyd Wright, who made one of his copper covers float over the Service Station in Cloquet, Minnesota, in 1958, and then, ten years later, Jean Prouvé was completely comfortable with redesigning the Total chain in France, and even Mies van der Rohe, the year of his death (1969), grappled with this subject on Nuns’ Island, Canada.

The 1960s were the years of the artist book and pop milestone by Ed Ruscha, Twenty-Six Gasoline Stations (1963) and of the Neo-futurism of the animated series The Jetsons (1962), which foresaw the raised edges of the 76 Station in Beverly Hills by William Pereira and the Tramway Gas Station by Albert Frey and Robson Chambers in California, both built in 1965. Between 1970 and 1971, once again, right before one of the 1900s biggest oil crisis, Vittorio De Feo won an Italian national award for his design of an Esso gas station, while Costantino Dardi and Giovanni Morabito designed the metaphysical light cube suspended over the Agip service station on the Mestre-Bazzera beltway, Italy.

With the end of the 1970s, a new, original, and very colorful, type of gas stations started to spread in the Soviet Union, from Kyiv to Baku, in the shape of flying saucers.

However, in the Post-modernism years, even these facilities, which are functionalist and technological at the core, were disguised with the local genius loci, like at the BP Station in Drakensberg, South Africa, the country where Denise Scott Brown grew up, co-author of Learning from Las Vegas (1972), the book that studied billboards and pop effects of the mass use of the automobiles on cities. But it was only in 1995 that Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates managed to build a gas station in Orlando, Florida: the Exxon Gas Station at Disney World, in a sense, the culmination of an entire career.

Even the era of the stararchitects stood out for its projects, like that of sir Norman Foster who redesigned the Repsol chain in Spain in 1998, while buildings with ever rounder shapes stand out in recent years, like the 2011 Gas Galanta in Matúškovo, Slovakia, by Atelier SAD or sharper shapes, and the service station integrated with a fast food by Khmaladze Architects in 2013 in Batumi, Georgia.