1986: a FIAT 131 has probably broken down and is now pausing at a service station along via Stalingrado, in Bologna. The bonnet is open, its content lightened up by the bright halo projected by a circular canopy. Luigi Ghirri captures the scene and includes it in one of its most famous photographic journeys, dedicated to his Esplorazioni sulla via Emilia (Explorations along the via Emilia). Ghirri’s research draws inspiration, amongst other references, from the 1970s American New Topographics, and similarly to them he unveils an ordinary landscape of cultivated fields and electricity pylons, countryside churches and malls, bus stops and derelict ruins. And of service stations, too.

The first gas pump comes into service one hundred years ago, in 1920. “A piece of our material history, of that minor history of things”: these are the words of Francesco Tacconi for Domus 764, October 1994, where he welcomes the publication of Decio Grassi’s Benzina, also showing a wide selection of pumps. This year centennial is an occasion to reflect not only on the object itself, the pump, but also on the spaces and architectures that were conceived to host it: the service stations.

It is commonly accepted that the first service station in history is a pharmacy in Wiesloch, a German town. This is where a fearless Bertha Benz makes a stop in 1888, as she drives the coach patented by her husband on the very first long-distance journey ever made by, and thanks to, an internal combustion engine. It is mostly a honorary title: a ritual is born in Wiesloch (the pit-stop for filling) but not yet a place. In fact, for many years fuel sale remains the preserve of local pharmacies and drugstores, which provide it in tanks, similarly to other fluids. Since the 1920 the invention of the pump and the multiplication of stations at roadsides result in a practical as well as spatial revolution.

View gallery

View gallery

Studio di architettura e urbanistica Marco Petreschi, electronic dispenser. From Domus 621, October 1981

Giò Ponti, Illusività dell’architettura. Presentation of Oscar Niemeyer’s Clube dos Quinhentos. The service station is mentioned amongst the club’s several structures. From Domus 277, December 1952

Bruno Cassetti, Max Chelli, Marco De Michelis, Maurizio di Puolo, Marco Fano, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

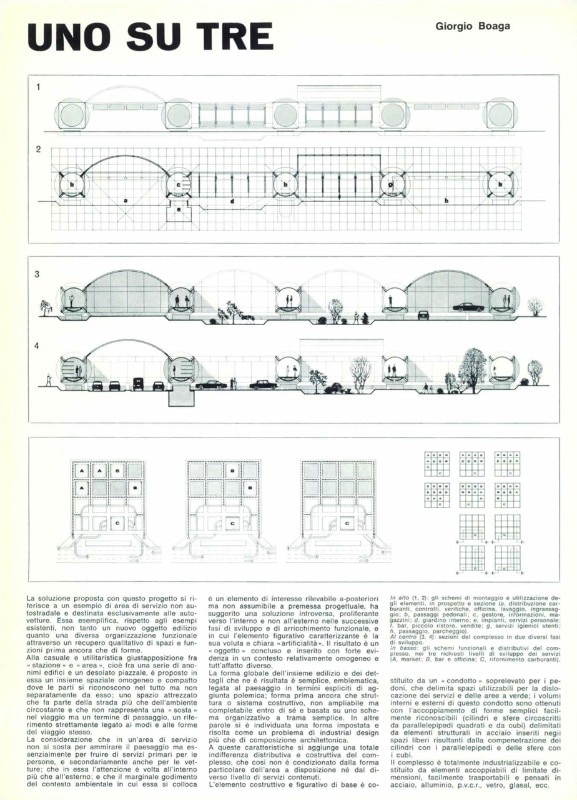

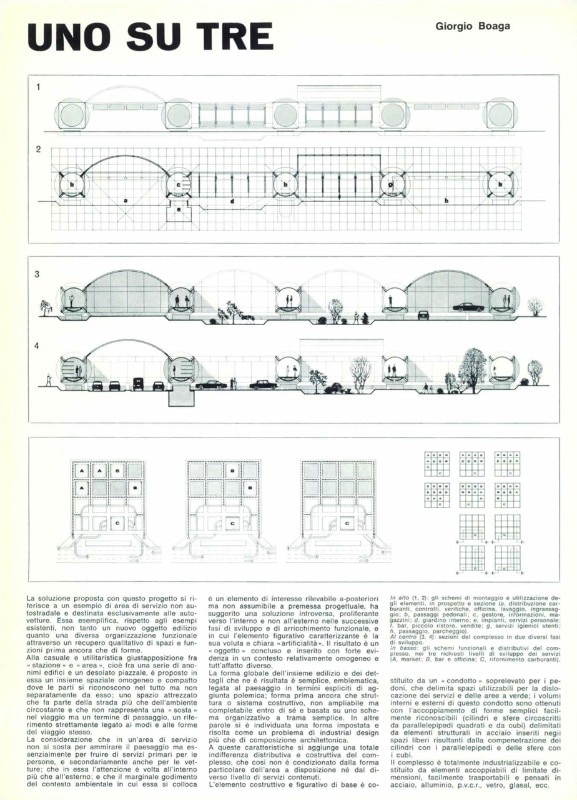

Giorgio Boaga, “Uno su tre”, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Mario Dal Mas, Manfredi Greco, “Scocca 70”, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Studio di architettura e urbanistica Marco Petreschi, electronic dispenser. From Domus 621, October 1981

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Minale Tattersfield & Acton, moveable filling stations, 1997. From Domus 797, October 1997

Giuseppe Terragni, projected standardized filling station, ca. 1940. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Camille Walala, Walala Pump & go gas station, Fort Smith, Arkansas, 2020. From Domus 1043, February 2020

Samyn and Partners, TOTALFINAELF service station and restaurant, Hellebecq, Belgium, 1999. Photo © Marie-Françoise Plissart

Samyn and Partners, TOTALFINAELF service station and restaurant, Hellebecq, Belgium, 1999. Photo © Marie-Françoise Plissart

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Studio di architettura e urbanistica Marco Petreschi, electronic dispenser. From Domus 621, October 1981

Giò Ponti, Illusività dell’architettura. Presentation of Oscar Niemeyer’s Clube dos Quinhentos. The service station is mentioned amongst the club’s several structures. From Domus 277, December 1952

Bruno Cassetti, Max Chelli, Marco De Michelis, Maurizio di Puolo, Marco Fano, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Giorgio Boaga, “Uno su tre”, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Mario Dal Mas, Manfredi Greco, “Scocca 70”, competition for the design of an AGIP service station, 1968. From Domus 470, January 1969

Studio di architettura e urbanistica Marco Petreschi, electronic dispenser. From Domus 621, October 1981

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc., service station, Orlando, Florida, 1995. Photo © Matt Wargo. From Domus 787, November 1996

Minale Tattersfield & Acton, moveable filling stations, 1997. From Domus 797, October 1997

Giuseppe Terragni, projected standardized filling station, ca. 1940. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Alessandro Bragaglia, Beppe Finessi, Antonio Fortugno, Ciro Mariani, Stefano Mirti, Matteo Pastore, Mario Pegoraro, Service stations. The Modern typology, Domus Itinerary 152. From Domus 811, January 1999

Camille Walala, Walala Pump & go gas station, Fort Smith, Arkansas, 2020. From Domus 1043, February 2020

Samyn and Partners, TOTALFINAELF service station and restaurant, Hellebecq, Belgium, 1999. Photo © Marie-Françoise Plissart

Samyn and Partners, TOTALFINAELF service station and restaurant, Hellebecq, Belgium, 1999. Photo © Marie-Françoise Plissart

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

Johnston Marklee, Office dA, Helios House, Los Angeles, 2007. Photo © Eric Staudenmaier

The market logic suggests to diversify the offer: not just fuel filling, but also checking oil level and tire pressure; glass washing and light and heavy repairs; furthermore, the sale of all those goods that can improve the quality of a journey. Therefore, the service station rapidly transforms from a technical theme (the installation of a device) into an architectural theme (the construction of a complex of structures and buildings). In 1932, Henry-Russell Hitchcock and Philip Johnson include a Standard Oil station in their historical exhibition Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, at New York’s MoMA. The service station is accepted and consecrated as a Modern typology, quoting the title of a compelling research featured on Domus 811, January 1999.

Virtually all of the great architects of the first half of the 20th century engage with it: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Frank Lloyd Wright, Robert Mallet-Stevens and Walter Gropius, amongst many others. Arne Jacobsen is the author of one of the most convincing realizations of this heroic age: in 1936, in Skovshoved, Denmark, he pairs a pristine rectangular-plan block with a tapered, mushroom-shaped canopy, clearly inspired by Wright’s work. The example of Skovshoved is representative of the contrasting, or at least complementary tensions that influence the design of a service station.

It must be iconic, a landmark catching the driver’s eye, but also functional, to speed up the filling operations. Besides, it can be designed as a one-off episode, an artwork in its own right, or it can function as a prototype, easy to replicate in order to rapidly expand its brand’s network. This twofold interpretational key is useful to understand the spatial and formal choices of all the best service stations.

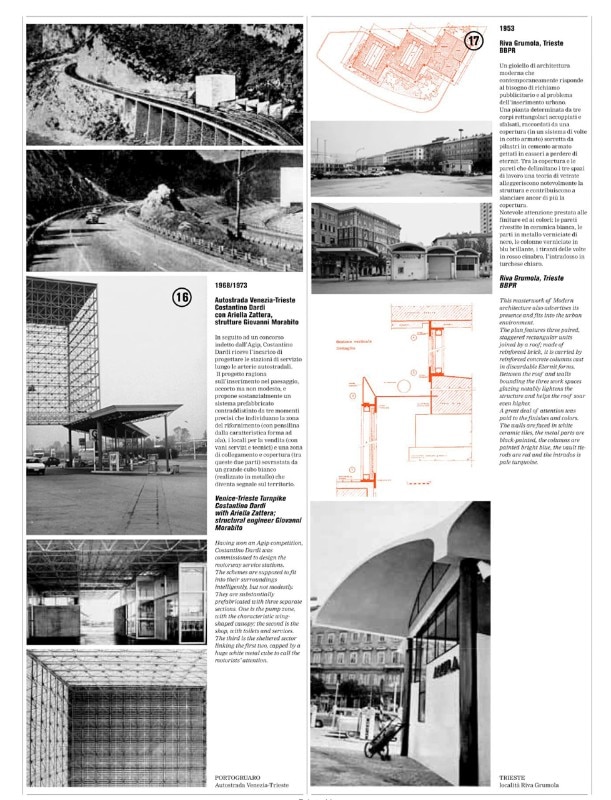

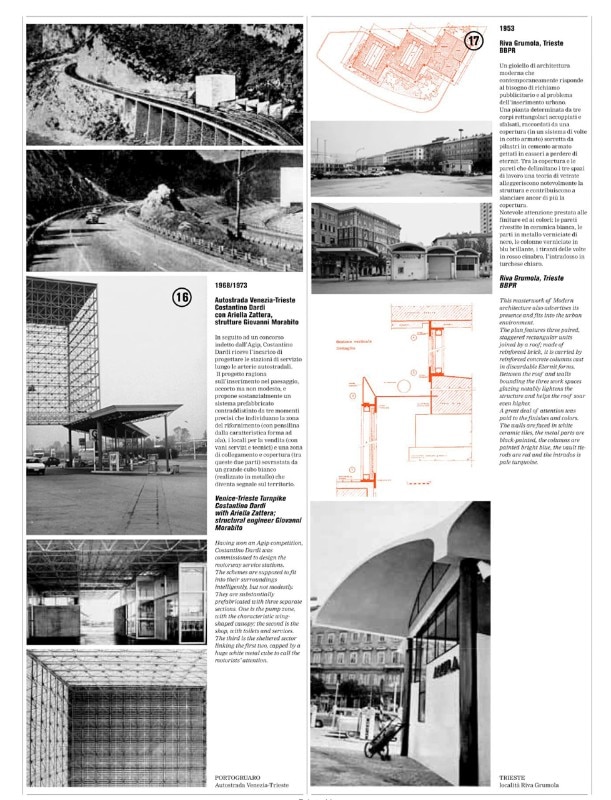

Many of them date back to the 1950s and the 1960s, the decades of mass motorization for nearly the entire Western Europe. Taking Italy as an example, stations are designed by that age’s “masters” of architecture (including BBPR, the authors of the Riva Grumola station in Trieste, completed in 1953) and of engineering (such as Aldo Favini, who invents the successful formal and structural solution of the station of viale Gramsci in Sesto San Giovanni, from 1955). It may also be remarked that the names of a few somewhat “minor” architects are connected in the first place to their service stations. This is the case, for instance, of Mario Bacciocchi, whom in 1953 completes the complex of piazzale Accursio, in Milano, a memorable streamlined prow of a common block in the city’s outskirts.

Italy is also the country where one of the most ingenious variations on this theme sees the light: the bridge-type autogrill, the outcome of the jointed visions of industrialist Mario Pavesi and architect Angelo Bianchetti. Two stations, on the opposite sides of a highway, are the gates to a huge, panoramic platform of commercial surface. The Italian highways are also the territory of another experimentation, equally remarkable if less known. The service stations designed in the 1960s and the 1970s by Costantino Dardi for the Venezia-Trieste highway replace the standard flat canopy with a three-dimensional, cubic scaffolding, multiplying vertical surfaces available for advertising and other messages.

The 1970s are also the age when the issue is raised, for the first time on a large scale, of the reuse of abandoned stations. In 1974 Albert L. Kerth publishes A new life for the abandoned service station, set to become a classic of the literature on this topic worldwide. Quick to realize but also to dismantle, vulnerable to traffic flows variations, service stations are a fragile heritage, easily ruined or lost, even when it comes to its most high-quality examples. In addition to this, over the last decade, the diversification of fuel typologies, and the gradual reorientation of the market towards electric and hybrid vehicles of various types, adds another dangerous variable.

Will the shift from the gas pump to the electric plug bring down the curtain on the history of service station once and for all? This is a question that will only be answered in the long run. Meanwhile, as Enel X’s charging stations are awarded a Compasso d’Oro ADI in September 2020, the traditional service station remains a vital architectural theme, both in terms of their design and rehabilitation.

Johnston Marklee and Office dA’s Helios House in Los Angeles (2008), alongside many stations realized in Belgium by Samyn and Partners, are good examples of the first category. On the other hand, what is likely the most brilliant transformation of the last few years is the work of London-based collective Assemble. Just steps away from London’s City, “The Cineroleum” (2010) repurposes the canopy of a disused station as the roof for a cinema, and the support to its shiny metal curtain. The existing ruin not only adapts to a new practice, but it suggests an unprecedented and surprising variation to it. The “ordinary” station, the one photographed by Ghirri and the New Topographics, turns into the stage of an extra-ordinary urban performance.