An aerial view: palm trees, golden majolica-clad domes, transition to the city Casino interior where Loretta Goggi recklessly approaches a gambling table singing Io nascerò (I will be born). This is the specific 1986 TV scenario for the headlines of Festival di Sanremo, but it can be replicated quite easily, with more or less roulettes, until today, replaced at most by a more generous drone. It is in any case the most complete picture we can get of the city of Sanremo during the six-day Festival of Italian popular songs that makes this seaside town a temporary cultural capital of Italy.

What might escape attention could be the presence of two, if not even three different cities that merge year after year to make a transformation, unthinkable elsewhere, possible: a polite Riviera resort turns into a situationist device, a communication machine making the early-stage Centre Pompidou blush, with its pop-up antennas and the unprecedented power available to its sound systems. A machine-city that now extends even into the sea, with a cruise ship dedicated to side shows that becomes some kind of a Fun palace, almost a "Floating City" worthy of the Archigrams. A New Babylon in the end, floating, like the Situationist city envisioned by Constant Nieuwenhuys, above an existing, static matter.

The festival is an Arabian phoenix, at least twice reborn between the 1970s and today, from ashes that have got ashier and ashier, which can only exist and be reborn in a place like Sanremo, an Arabian phoenix as well, which, however, seems to like lying in its own ashes a lot, with no particular desire to shake them off except in recent times of building superbonuses.

This is what Emiliano Colasanti, A&R executive of the independent label 42 Records, also told us. He attended his first Festival as a journalist, in 2000, and now that he is participating in his sixth edition as a producer, with Colapesce and Dimartino, he confirms that the human geography of the city might have quite certainly changed, as far as the music system is concerned, but the physical geography, the building geography surely has not: “You find yourself torn between three cities, the small hectic pop-up city around the two blocks of the Festival, the perfectly indifferent ancient one, and then all that luxurious and decadent world, the big hotels and villas, serving some shade of Twin Peaks”.

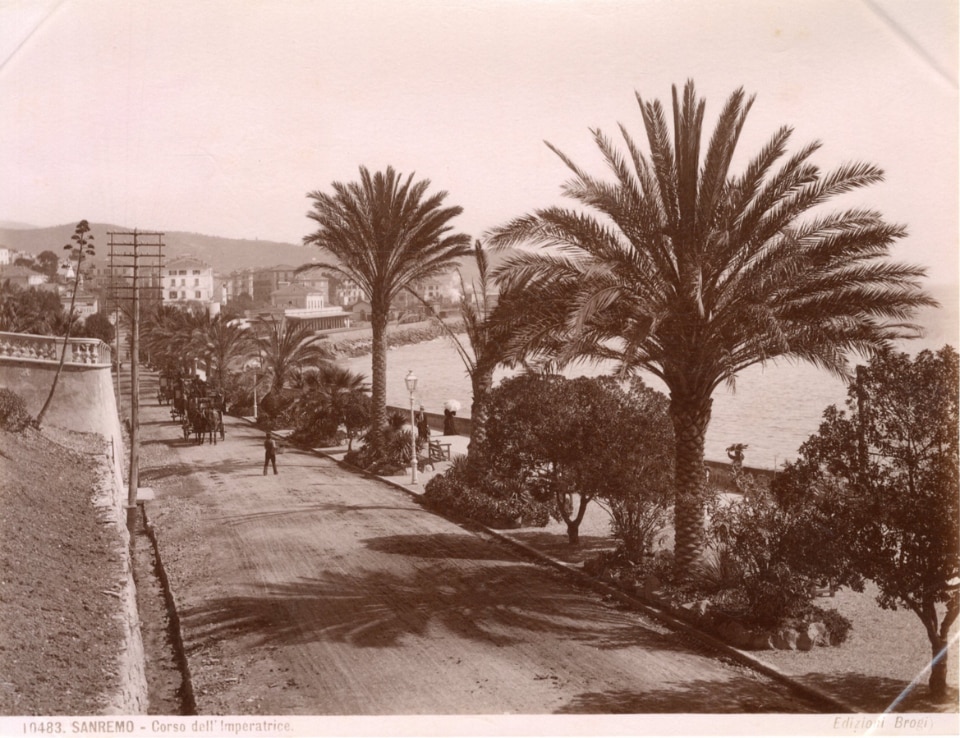

For that materia over which the Festival’s situationism is stretched is actually something that was born quickly, and quickly crystallized, a materia that spread over the entire Foce area and the hills around, with the grand villas of an international elite attracted to the Flower Riviera in the late nineteenth century, the vanished Marsaglia Castle, the Devachan Castle, the villa Angerer, and the villa where Alfred Nobel ended his days in 1896, leaving a garden that welds with the villa Ormond right behind to grant the public a small share of that decadence that seems to be the real building material of the entire city. Then came the grand hotels, the Londra, the des Anglais, the Royal, sometimes to replace the villas, today to extend the early twentieth century into our times (one almost comes to decline all wifi offers just not to spoil such a precious time capsule), and very often to offer their somewhat time-tarnished masses to our view. “The facades are being renovated with the 110 (the building renovation bonus), the interiors still look the same they did years and years ago” Colasanti says again.

A sumptuous and timeless matter granting access to a select few newcomers, be they the people of the Festival, or a handful of architectural episodes from the Modern: the swimming pool at the Royal, mosaics and organic shapes with which Gio Ponti carried on the glories of the luxury vacations from the past in the 50s; the Marina di Capo Nero complex by Luigi Carlo Daneri, which earned compliments from Le Corbusier by the opening time of its abstract masses, anchored among waves, rocks, and pine trees (with some Brutalist concessions); and then comes the Ariston.

Eighty years old this year, the cinema-theater that since 1977 has taken away from the Casino the sanctum sanctorum, the stage of the Festival, gifts us with another time capsule, from its original forms defined by Marco Lavarello in the 1950s – among “pleated” ceilings, cluster lighting, prototypes signed by Italian atelier Barovier e Toso – that breathing the air of Italy’s postwar rebirth, of the last season of steamships, to the almost illegible shapes of today, transformed as they are into the core of the Sanremo machine. Today’s Ariston is the modernist box housing an increasingly mammoth and loudly technological stage (is it possible, after 7 decades, to speak of some “national broadcasting system style”, a “RAI style”, at last?), the classic staircase – be they Freddy Mercury or Patty Pravo in japoniste Versace to descend it – and another semiotic fetish, the local flowers, that have finally found an inedited use in 2023, kicked and smashed by Blanco across all available space.

Then comes that other city, the one that has been there from the beginning, equally indifferent to the Belle Epoque transformation and to every Festival that history has sent down, a realm that begins as soon as one leaves via Palazzo, passing under a wall of houses and beginning a mountaineering-style ascent from the square right behind, through narrow streets that rarely see the light of day, covered as they are by floors and floors of houses, medieval geological caves suddenly opening into squares from which the clamour of live performances and events can only be heard and not seen, often with results that are once again close to science fiction: this is La Pigna, the high city rarely penetrated by the human geography of the Festival, which many, as our Colasanti did, might happen to discover only after several years of presence in town.

It is a plastic representation of that double speed on which the Sanremo flow is set: if on the one hand it got rid of the coastal railway, tightening the connection to a sea otherwise far from its heart, on the other hand it embeds the new station deep in the hillside, enriching itself with another natural/artificial, cave from which trolleys and people, another fundamental piece of the situationist machine, spill in a continuous flow.

If lived as a Festival scenario, Sanremo is a mental entity, so much that it can detach itself from those physical limits that we seemed to be seeking all across the article: let us not forget, in fact, that back in 1990 the Sanremo Festival was held in Arma di Taggia, not far away but still not Sanremo. The Palafiori – the real one, not the convention centre a stone throw from the Ariston – was a shed within the enormous Valle Armea flower market, which was difficult to fill with public, with a mile-high floor from which bats kept hanging all the time, even during the live broadcasts, much to the annoyance of Liza Minnelli, that year’s guest.

Without being able to place it precisely, to this day, that megastructural presence, together with the Pigna, keeps receiving the echo of the six noisiest days in the country, and together with the Liberty facades and the organicist swimming pools it keeps being part of some constitutional psychogeography, a matrix of sense without which nothing of all this would be possible. In a nutshell, because Sanremo is Sanremo.

A prize for architecture between lights and volumes: LFA Award

An international photography competition that invites photographers worldwide to capture the essence of contemporary architecture. Inspired by the work of the famous Portuguese photographer Luis Ferreira Alves, the award seeks images that explore the dialogue between man and space.

.jpeg.foto.tbig.jpg)