“Everything this decade is going to leave us is memes.” Such statement, still often pronounced with some shade of contempt, is usually generating two kinds of reaction, “Ok boomer” being the first, “This is so true” the second. Fun fact: both reactions are very likely to be correct.

Debate arenas have been keen on shapeshifting since forever. In architectural history as well as in history in a broad sense, there comes that time when one can feel the place of discussion moving, a sort of FOMO (that fear of missing out which has ravaged the last decade) affecting the realm of theory and debate: very rarely architecture, despite being probably one of the most loquacious disciplines, has recognized at the right time, or in real time at least, the places and medias that were actually shaping and pushing forward its disciplinary debate.

In the middle of a contemporary dimension which could hardly be most postmodern than this, nothing can cross paths with the largest number of different realms, issues, levels of agency and information better than memes, than the transposition of meanings they operate, than their claim for internet ugly as a weapon against glossy official, power- validated aesthetics and communication.

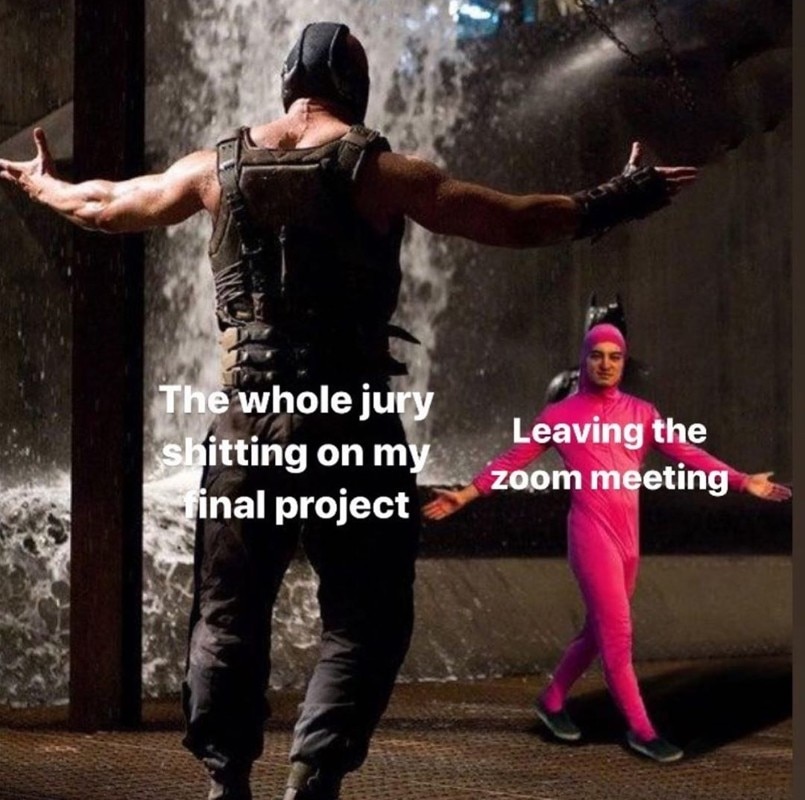

The unpaid internships issue boosted through social media campaigns such as last year’s one by Adam Nathaniel Furman, and the ominous meme wave it generated, should stand as a powerful signal of how the memesphere has become “the hot issues factory”, the place where contemporary issues upgrade their scale and relevance, architectural issues as well. Memes nowadays are ugly, filthy, most of the times dumb, and bad for real, they give sense to our morning compulsive scrolling, and as they make us laugh they assault the architecture world in its being “white, western, tone-deaf, complacent, (with) this weird power struggle where architects act like they have a lot of power but are really just rolling with the people that actually do have power”.

Disciplinary debate is no longer relating only to aesthetic or official policies, memes are no longer drawing from lame jokes on clients, lack of sleep or coffee: architecture itself can no longer call itself extraneous to an articulated contemporary dimension, made more of issues of racism, sexism, economic and social divide, than façade patterns.

Domus has therefore exchanged some words with some meme accounts from the architectural world, in an attempted experiment of “meme psychoanalysis”, trying to get memers looking at themselves from outside and giving a synthetic account — also including what you have read so far — of Just what is it that makes memes so different, so appealing? In a word, the origins and possible limits of the critique that the memesphere is making of contemporary world.

Ryan Scavnicky (@sssscavvvv), an architecture graduate active in theory and teaching, not exactly a newcomer on architectural press, is already a peculiar figure as he connects a face and a name to an instagram meme account, but that’s exactly the core of his program: associating critique (have you ever tried his Rhino modeling tips?) to a new kind of figure, personally responsible in forcing the boundaries between what is inside and outside the discipline. His project is also to get the largest number of people making memes and fostering the discourse, an urge born from a frustration about communication in architecture, which is always based on positive and one-hundred-per-cent disciplinary narratives.

A similar frustration has generated OH EM AYY (@oh.em.ayy) in late 2018, a strictly anonymous account aiming to prolong the spirit of undergraduate years in architecture school, but opening the space to all kinds of critique that are usually forbidden within the majority of — American — schools, i.e. everything going beyond aesthetics or techniques: “the discussion in architecture schools is basic, not democratic at all, all social aspects ad the ways architecture can affect the life of entire urban communities remain a taboo”

Such taboos are for sure the main course of Dank Lloyd Wright’s (@dank.lloyd.wright , also the source to some of the previous quotes) savage memetic binges. A collective entity looking towards all the world “off the West seabord of Ohio”, “...reborn as a parasitic pup out of the resuscitated corpse of Frank Wright The BasedGod when Covid was first popping off”, DLW aims to call out the many hypocrisies extant in the world of architecture today, locate an architect’s agency more accurately as it is nested in intersected systems and power structures, and obtain the immediate retirement of the cult of the individual. From DLW’s point of view, memes are some kind of a Spongebob, serving easy jokes for children while passing deeper ones for their parents, memes are “…quick and dirty, easy to consume. Their ugliness and impulse narrative mock what we’re against.”

DLW has often been pointing out connections between specific aesthetics and specific political position, as it doesn’t think aesthetics are independent from power, so the point becomes to “demolish the white male Eurocentric architectural canon and help rewrite history with accuracy and representation and remove rapists, snake oil salesmen, and shameless grifters while we are at it.” People from DLW affirm they like history, they learn it, use it, problematize it and make jokes with it, not to get “stuck in old ways of understanding”.

A most peculiar subject within this scene is Alvar Aaltissimo (@alvaraaltissimo), blossoming in 2016 from the Italian foam of Politecnico di Milano (alto in Italian means tall, altissimo means the tallest) , starting his expression through videos to then become a celebrated meme architect. He appears in fact through projects, totally careless of all despotic dynamics of the internet, silent for months then literally logorrheic for days, his opinion and mission being a war against two fundamental aspects of architectural practice, the Italian one in particular: triviality, and a tendency to a constant defeatist complaint.. Alvar Aaltissimo claims he has a solutionist attitude: step forward, propose, let the discipline show some self-love and some agency through its dialectical and professional tools. Hence a research on historical projects (did you know that Italian Modern master Luigi Moretti once designed a house for prime minister Giulio Andreotti in Castel Gandolfo, close to the Pope’s summer residence?) but also museums for to-be-taken-down statues, or territorial-scaled solutions for post-Covid seaside holidays in Italy.

As we keep listening to understand whether all this can be a tool to get in control of the contemporary postmodern communication juggernaut, or part of its expression, for sure we will no longer run BIM software, or look at the celebrated body of Le Corbusier, the same way we did before, and we might as well entrust cartoon satire to the realm of scholarly retrospectives and vintage fine arts auctions.

Franke presents “The House of Well-Living” at Fuorisalone

With a multi-sensory installation, Franke will welcome visitors to its flagship store during Milan Design Week and present the year's new products.