“Anyone who has ever stood with their back to the Palazzo Pubblico will have tried to imagine different buildings surrounding the Campo and will probably not have thought of anything scandalous”. (pages 94-95)

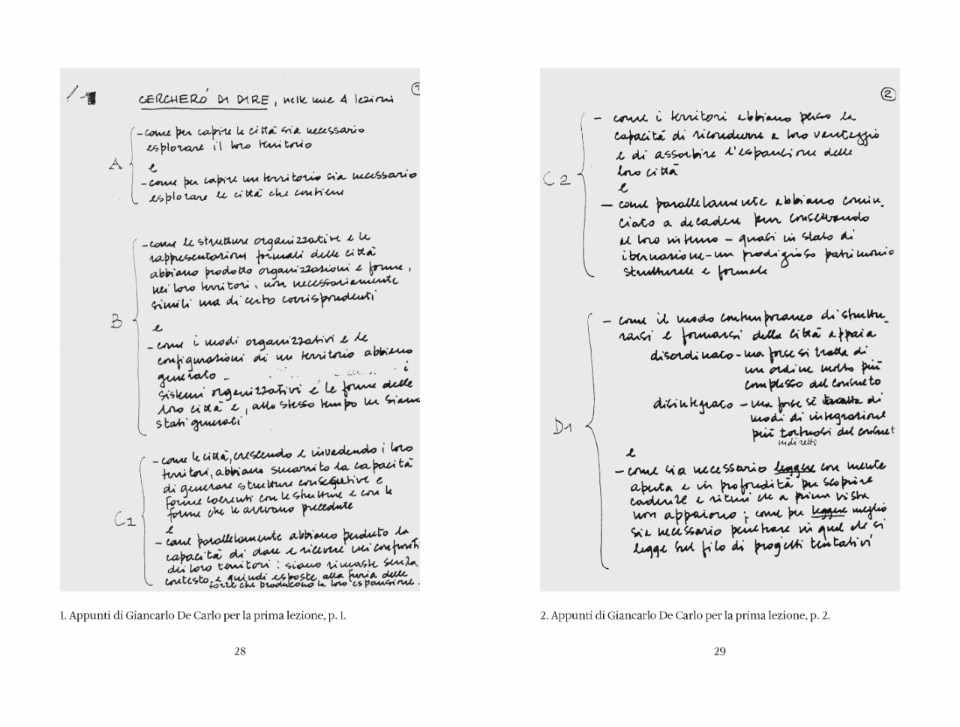

These words on Piazza del Campo in Siena sum up the sense of the four lessons on the city and the territory held by Giancarlo De Carlo at the Department of Architecture in Genoa in 1993 at the end of an academic career that lasted for four decades, and which have now been transcribed in the book The city and the territory: Four lessons (published by Quodlibet, 2019). The lessons, published here for the first time ever, are introduced by Clelia Tuscano who, by no coincidence, has identified the key role of this particular passage on the Campo.

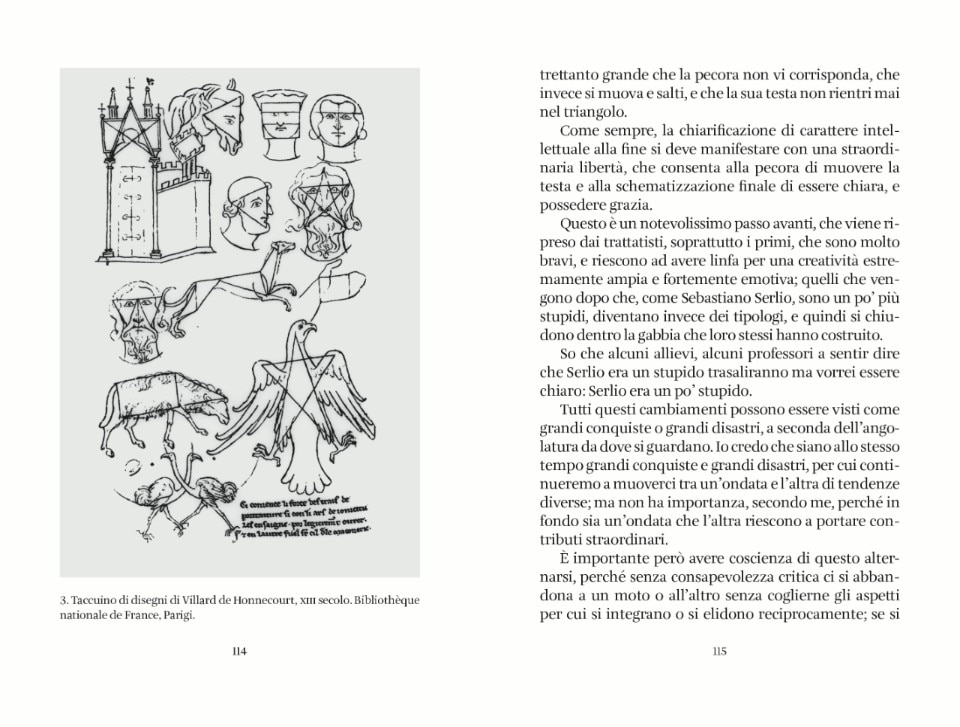

These are words that it is not hard to imagine being pronounced by the man who, more than twenty years earlier, had declared that architecture is too important to be left to architects. On closer reflection, what De Carlo now seems to be saying is that architecture in itself is not even that necessary or irreplaceable, at least when seen from a restricted point of view, as a building in itself. More than a series of buildings surrounding an empty space, more than the result of architectural “types” resulting from those “typologies” often referred to in an accusatory manner by De Carlo over the course of the four lessons, Piazza del Campo in Siena is first and foremost an open space, with open meaning free and a champion of freedom. Freedom - a word already widely associated with the Genoese architect and, probably, one of the ones he pronounced most often during these four excursions into the history of the relationship between the city and its territory, aimed at demonstrating how space should never be coercion but rather a point of reference, stimulus for thought, doubt, pleasure and free will. And also for the right to revolt, as symbolised by the attempt by Villard de Honnecourt to rationalise the outline of a sheep by placing it within a geometric shape, to then reveal to De Carlo the “important discovery” that, on closer examination, the sheep did not correspond to this form of abstraction, but that “instead it moved and jumped, and its head never remained within the confines of the triangle” (p. 115).

Without fear of being overly ambitious, and even less of hiding his own opinions, De Carlo crammed into less than ten hours - now presented in a pocket-sized book - a story of more than two thousand years in length, seeking to demonstrate how architecture or the city cannot exist without a territory. This is a constant in human development that De Carlo identifies from as far back as ancient Greece right up to the modern-day tendency for dematerialisation, examining cases that are obvious, yet never handled in an obvious manner. De Carlo’s secret to debunking the obvious lies in the choice to move in a wide field which again reminds us how architecture is merely a fragment of thought that desperately relies on alliance with others. On the one hand, the lessons examine truly disciplinary, architectural or urban examples that span ancient times, the Medieval, the Renaissance, Enlightenment and the Modernist Movement, ranging from Miletus to the Acropolis, from the Monastery of San Gallo to the Rome of Sixtus V, from Pio II Square in Pienza to Godin’s Familistère, and from Plan Voisin to the car parks at Disneyworld. In order to understand the first examples from a point of view that goes beyond architecture, De Carlo brings into play Homer, Virgil, Boccaccio, Rousseau, Valéry and Vittorini among others because, as he says, “I believe that the only way to conceive an idea of territory that is not derived from specialisation [...] is to look to writers” (p. 42).

De Carlo’s message is clear and in line with his juvenile warning to not leave architecture to architects alone. The world created by specialisation is a sad world as it is devoid of the capacity to see things in a wider context. More generally, the sense of the lessons lies in a certain way of examining reality with an attitude that is open to curiosity, irony and optimism (and in what other manner, in fact, can one read the pages regarding the rediscovery of the territory in the period following the Medieval plague, inevitably charged with special meaning in this particular moment in history?) At the same time, the words of De Carlo stress the importance of lightness, multiplicity and exactitude. I draw these terms from the the titles of three of the “six memos for the next millennium” that Italo Calvino prepared as a series of lessons to be held at Harvard University in 1985. This is no casual choice, as the reading of De Carlo’s lessons often leads to Calvino, partially in a direct manner through the many quotes and eulogies that the architect dedicates to his author friend, but also to some extent because what the two have in common is the common ability to dispense wisdom without the heaviness of the worst form of know-it-all. Both demonstrate the importance of the lesson, a form of communication that is perhaps too easily (and trivially) discredited nowadays in the name of the presumed superiority of more interactive ways of teaching and learning compared to the more (allegedly) coercive frontal approach of the lesson. Besides, one could not expect anything else from two thinkers whose resistance to imposed authority was extensively documented.

Fortunately, unlike the Harvard lecture hall that was denied the voice of Calvino due to his untimely death, fate was kinder to De Carlo and the Architecture lecture hall in Genoa where the last four lessons by the architect were held. It was also fortunate that the decision was taken to render these lessons collective heritage, despite running the inevitable risk that the pleasure of reading them can never compensate for the jealousy felt towards those who attended them at the time.

Accademia Tadini on Lake Iseo reborn with Isotec

Brianza Plastica's Isotec thermal insulation system played a key role in the restoration of Palazzo Tadini, a masterpiece of Lombard neoclassical architecture and a landmark of the art world.