Inspired by nature

Fast, a company founded in 1995 in Valle Sabbia by the Levrangi family, is specialised in outdoor furniture, representing the best of made-in-Italy quality.

- Sponsored content

Until the mid-eighteenth century, the European coasts used to represent the dangerous gateway of a continent with a thriving hinterland. These were wild territories, always guarded by fortified ports and forced passages for all strangers and goods. The rise of seaside tourism was also boosted by a radical transformation of the collective image of seas and oceans: from stormy abysses they became beneficial basins, with healing and (later on) recreational properties. On the coasts, that turned from a threatening place to a promising seafront, began a centuries-old process of construction of architectures and infrastructures for tourism, created by and for the use of non-native populations. And in many cases, it became a veritable "colonization" of virgin territories.

The long history of seaside holiday camps, finding its roots in Italy in the 1820s, is a clear example of the approach to coastal urbanisation: public and private companies, as well as laic and religious associations, used to build isolated complexes on the seashore hosting clearly defined communities of "foreigners".

In March 1985, Domus 659 dedicated a long study to the Italian summer holiday camps of the 1930s. The cover of the issue showed a nice detail of the holiday camp "Le Navi" in Cattolica, designed by Michele Busiri Vici (1932, originally known as Colonia Marina "28 ottobre”) overlapping the main image: a wonderful portrait of Grace Jones, more geometric than ever, in a controlled explosion of tapered lines and tulle. The unexpected juxtaposition between the fashion icon and the architecture icon suggests some reflection on the formal values of this heritage.

As Fulvio Irace pointed out in his essay for Domus, the fascist regime wanted these buildings to be "formidable propaganda machines dedicated to the working classes". At the same time, they "constituted a laboratory of experimentation for those young architects eager to test in a real project the effectiveness of their ethical and aesthetic ideals (...). Modern architecture proved to be able to fully grasp the expressive potential of this new theme". It was "an extraordinary opportunity to experiment with an isolated object alone in the landscape. It constituted a really important moment for all European rationalism".

The systematically iconic characteristics of the holiday camps during Italy's fascist era derive precisely from the merging of the interests of a dictatorship hungry for symbols and slogans with those of a generation of designers looking for new aesthetics. Domus's retrospective shows the multiplicity of references and evocations: "Le Navi" by Busiri Vici recalls "an abstract and unreal image (...) of landed flying saucers, or Disneyland-like constructions"; the "Agip" holiday camp in Cesenatico, by Giuseppe Vaccaro (1937-1938, originally called "Sandro Mussolini") is a "monolith resting between the road and the sea"; the holiday camp of Chiavari, by Camillo Nardi Greco (1935) looks “like an “arengario” tower, or even a structure containing water tanks. It is a direct hint to the deck of a ship or a poetic citation of lighthouses".

View gallery

View gallery

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Camillo Nardi Greco, seaside holiday camp, Chiavari, Italy, 1935

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Giuseppe Vaccaro, seaside holiday camp "Agip", Cesenatico, Italy, 1937-1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Giuseppe Vaccaro, seaside holiday camp "Agip", Cesenatico, Italy, 1937-1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Giuseppe Vaccaro, seaside holiday camp "Agip", Cesenatico, Italy, 1937-1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Mario Loreti, seaside holiday camp "Costanzo Ciano", Milano Marittima, Italy, 1937-1939. Photo © Massimo Simini

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Mario Loreti, seaside holiday camp "Costanzo Ciano", Milano Marittima, Italy, 1937-1939. Photo © Massimo Simini

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Mario Loreti, seaside holiday camp "Costanzo Ciano", Milano Marittima, Italy, 1937-1939. Photo © Massimo Simini

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Vittorio Bonadè Bottino, seaside holiday camp Fiat "Edoardo AgnellI", Marina di Massa, Italy, 1933. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Montanari, former Italian Red Cross seaside holiday camp, Marina di Ravenna, Italy, 1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Montanari, former Italian Red Cross seaside holiday camp, Marina di Ravenna, Italy, 1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Angiolo Mazzoni, seaside holiday camp, Calambrone, Italy, 1925-1933. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Angiolo Mazzoni, seaside holiday camp, Calambrone, Italy, 1925-1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Angiolo Mazzoni, seaside holiday camp, Calambrone, Italy, 1925-1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Angiolo Mazzoni, seaside holiday camp, Calambrone, Italy, 1925-1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Ettore Sottsass, Alfio Guaitoli, seaside holiday camp "28 ottobre", Marina di Massa, Italy, 1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Ettore Sottsass, Alfio Guaitoli, seaside holiday camp "28 ottobre", Marina di Massa, Italy, 1938

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Ettore Sottsass, Alfio Guaitoli, seaside holiday camp "28 ottobre", Marina di Massa, Italy, 1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Camillo Nardi Greco, seaside holiday camp, Chiavari, Italy, 1935

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Michele Busiri Vici, seaside holiday camp "Le Navi", Cattolica, Italy, 1932

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Giuseppe Vaccaro, seaside holiday camp "Agip", Cesenatico, Italy, 1937-1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Giuseppe Vaccaro, seaside holiday camp "Agip", Cesenatico, Italy, 1937-1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Giuseppe Vaccaro, seaside holiday camp "Agip", Cesenatico, Italy, 1937-1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Mario Loreti, seaside holiday camp "Costanzo Ciano", Milano Marittima, Italy, 1937-1939. Photo © Massimo Simini

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Mario Loreti, seaside holiday camp "Costanzo Ciano", Milano Marittima, Italy, 1937-1939. Photo © Massimo Simini

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Mario Loreti, seaside holiday camp "Costanzo Ciano", Milano Marittima, Italy, 1937-1939. Photo © Massimo Simini

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Vittorio Bonadè Bottino, seaside holiday camp Fiat "Edoardo AgnellI", Marina di Massa, Italy, 1933. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Montanari, former Italian Red Cross seaside holiday camp, Marina di Ravenna, Italy, 1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Montanari, former Italian Red Cross seaside holiday camp, Marina di Ravenna, Italy, 1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Angiolo Mazzoni, seaside holiday camp, Calambrone, Italy, 1925-1933. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Angiolo Mazzoni, seaside holiday camp, Calambrone, Italy, 1925-1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Angiolo Mazzoni, seaside holiday camp, Calambrone, Italy, 1925-1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Angiolo Mazzoni, seaside holiday camp, Calambrone, Italy, 1925-1933

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Ettore Sottsass, Alfio Guaitoli, seaside holiday camp "28 ottobre", Marina di Massa, Italy, 1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Ettore Sottsass, Alfio Guaitoli, seaside holiday camp "28 ottobre", Marina di Massa, Italy, 1938

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Ettore Sottsass, Alfio Guaitoli, seaside holiday camp "28 ottobre", Marina di Massa, Italy, 1938. Photo © Gabriele Basilico

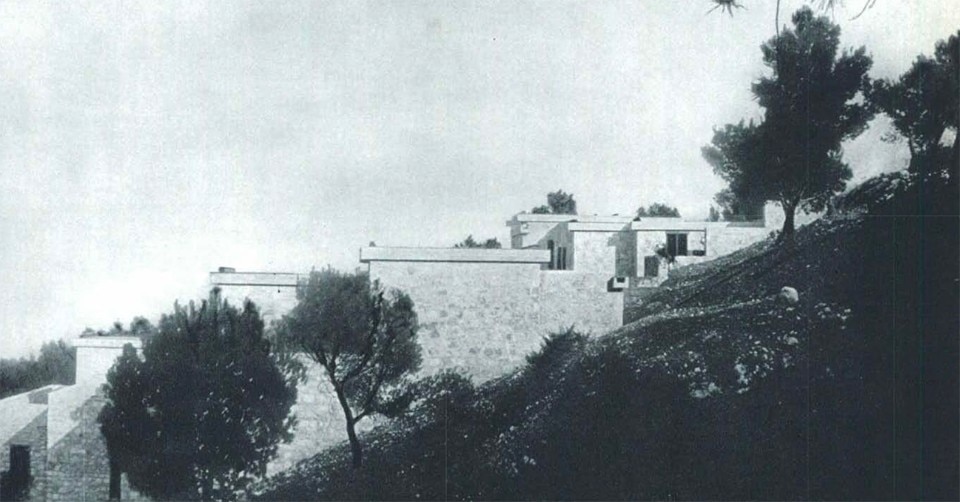

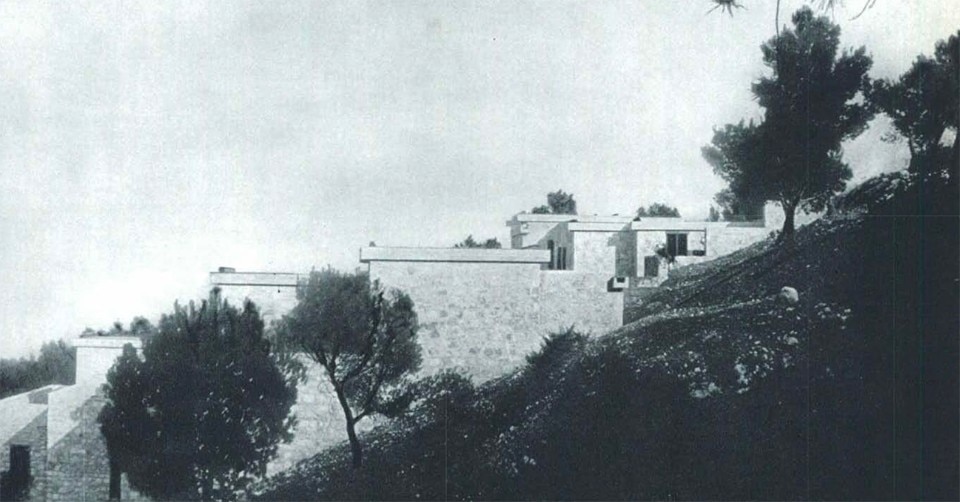

After the war, some large state-owned companies were the protagonists of the last (for the moment) "flowering" of holiday camps in Italy, both at the seaside and in the mountains: for example, ENEL and ENI, whose (unfinished) holiday camp in Borca di Cadore, designed by Edoardo Gellner (1955-1962) remains one of the most ambitious and successful achievements of this kind. In August 1970, another lesser-known operation, promoted by the company led by Enrico Mattei, was featured on the pages of Domus 489: the village of Pugnochiuso, on the Gargano, completed in 1969.

This project was carried out in southern Italy by Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, a Milanese trio that is mostly famous for the (re)construction of Milan after the Second World War. The type of client, the choice of the architects, as well as the "firm" way of managing the project (for example, ENI required, among other things, the deviation of the coastal state road under construction, so that it would not interfere with the building): these are some of the many elements that are in continuity with the colonising attitude of the previous decades. Here they are also combined with the paternalism that northern Italian industrials used to show towards a southern Italy constantly hoping for further development.

But during this more mature phase of Italian modernism, the relationship between architecture and nature was completely different compared to the period of fascism. In the Italian Far South, where everything seemed to be allowed, the Monti project aspired as much to a formal autonomy as to a respectful integration into the landscape. "Many low buildings are part of a single design that includes paths, squares, walls and green areas, all strictly following the unevenness of the terrain (...). The building of the 'Centre' has been conceived as a wide and low 'pyramid' (...) cut on three sides by large staircases, which connect the building to the paths at different levels".

View gallery

View gallery

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, SNAM holiday camp, Pugnochiuso, Italy, 1969

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, SNAM holiday camp, Pugnochiuso, Italy, 1969

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, SNAM holiday camp, Pugnochiuso, Italy, 1969

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, SNAM holiday camp, Pugnochiuso, Italy, 1969

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, SNAM holiday camp, Pugnochiuso, Italy, 1969

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, SNAM holiday camp, Pugnochiuso, Italy, 1969

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, SNAM holiday camp, Pugnochiuso, Italy, 1969

Coastal icons: Italian holiday camps, from Mussolini to Valtur

Gianemilio, Piero and Anna Monti, SNAM holiday camp, Pugnochiuso, Italy, 1969

In the history of seaside architecture, the village of Pugnochiuso is a high-quality, but certainly not unprecedented, interpretation of the theme of building integration into the surrounding landscape; in the frame of this brief excursus on summer holiday camps at the seaside, it symbolises the denial of the totem. On the increasingly familiar, urbanized and populated coasts, the building lost its usefulness as a milestone and almost disappeared, laying on the ground.

Originally designed for SNAM employees, Pugnochiuso was immediately made accessible to the general public. At the time of mass leisure, the cohesion and social relevance of the corporate community lost popularity, while the members discovered and joined new experimental forms of coastal gated communities. The notorious hotel empire of Valorizzazione Turistica began to rise. In other words, the golden age of Valtur villages had begun.

Bathed in light

Drawing from its more than 30 years of experience, SICIS introduces backlit pools in Vetrite, a patented solution that combines design, technology and function.

- Sponsored content