Text by Rita Capezzuto

Photography by Gerald Zugmann

Nuremberg has been trying to deal with its recent past ever since 1945. In particular with the Kongresshalle, which though incomplete, is the largest Nazi building in Germany to survive the war. Its troublesome origins were anathema to the democratic ambitions of the Federal Republic, and it stood empty until 1949, when it was used for a while as an exhibition and trade fair site. Since then Nuremberg has considered everything from outright demolition to its conversion into a sports stadium, or even, absurdly, in the 1980s, into a shopping mall. Its size, a massive 275 x 265 metres, its architectural style, and above all its history make it an uncomfortable legacy. Its fate became the object of endless argument between those in favour of removing all traces of national socialism from the new Germany, and those who advocate the preservation of the physical records of that period not to glorify it, but as a reminder and a warning.

Nowhere is the question between the two approaches posed more sharply than in Nuremberg, the city that was officially designated as the ‘city of party congresses’ by Hitler in 1933. This was where, every September until 1938, the Nazi regime put on its greatest spectacles, attracting up to a million people.

The Kongresshalle was an essential architectural backdrop to those congresses, specially built for the purpose in a parkland area south east of the city.

Begun in 1935, it was designed in the image of the Colosseum, but never completed. The roof that would have transformed the vast enclosure into a hall to seat 50,000 spectators was technologically beyond the resources even of the Reich. The project, by Ludwig Ruff, was continued by his son Franz even after the outbreak of war, and construction went on until 1942.

It was a monumental task, and an expensive one. Marshy ground conditions caused structural problems, as did the sheer weight of the massive granite cladding, the rough-cutting of which was done by the inmates of concentration camps.

In its semi-finished condition, with its interiors still in their rough state, and with its unfaced brick courtyard, the Nuremberg Colosseum survived not just the war but also the postwar arguments about its future, and in 1973 was finally declared a historic monument. Its more managable sections were rented out as storage or rehearsal rooms for the Nuremberg symphony orchestra. But there is no sign of these new functions on the outside, and the building stands as a blank and faintly sinister reminder of things past. Its context does nothing to help, especially in the light of winter: with nobody about, fields populated only by crows, and close to it a main road with traffic whizzing past. Only the water of the Dutzendteich, in which the Kongresshalle is mirrored, softens the image of a ghostly legacy.

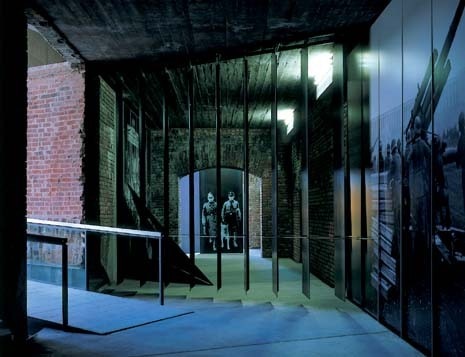

All of which only serves to accentuate the shock of discovering that the flat granite of the north facade has been pierced by a pointed glass and steel arrow, surmounted by an equally strident glass and aluminium shape. This dramatic dissonace was deliberately introduced by Günther Domenig – the Austrian architect best known for his continuing scultpural work in progress the Steinhaus – to distinguish his new Centre for the Documentation of the History of the Third Reich. The cantilevered entrance is so brutally sharp that it seems to foreshadow the unsavoury nature of the material inside. But it also serves to protect the stairs, which skip the base and lead straight into the main atrium on the first floor. Here at a glance one grasps the project’s conceptual, formal and structural breadth: the new, sharply distanced from the old in its materials; the system of vertical communications all packed together at the beginning of the route; the spine of the long and narrow corridor (130 x 1.8 metres), out of line with the symmetrical plan and elongated through the whole of the north end, until it comes out into the open again in the horseshoe-courtyard; and finally, the sculptured concrete floor slab of the auditorium, treated as a Brutalist decorative feature of the entrance hall.

Domenig (who won the commission after an invited competition held in 1998 by Nuremberg city council) sees the design as based on contrasting stresses: ‘I used oblique lines against the existing symmetry and its ideological significance. To contrast the heaviness of the concrete, brick and granite I turned to lighter materials: glass, steel and aluminium. The historic walls are left in their original state, without ever being touched by the new work’. All the exhibition rooms are carved out of existing spaces, which retain their original gloom. In comparison, Domenig’s arrow running right through the work of a criminal regime is the tormented signal introduced by the architect. The seminar rooms are treated in a more relaxed way. They are completely new, full of light and offer unbroken views. Almost consolatory, they are gathered into the block that juts out above the entrance to the Centre. Reflection on the crimes of the past does not necessarily entail the physical oppression of present day scholars.

There could be no better place to put an institution that attempts to come to terms with the dark heart of the Nazi nightmare. It dominates the 11 square kilometres of Albert Speer’s master plan drawn up in 1934 to accomodate the party’s annual congresses. Nazi propaganda depended on an enormous scale as well as on classically inspired architecture. Everything here was on a gargantuan scale.

An avenue, two kilometres long and 60 metres wide, served as the main axis to the complex, symbolically connecting it with medieval Nuremberg. Its granite paving was left rough, to provide the friction needed for soldiers’ boots to execute drill steps, as Speer put it. The avenue is still there, providing a car park for visitors to the trade fair. It originally opened onto a parade ground, almost one kilometre square designed for military tattoos. This was to have been surrounded by stands and tiered seating for 160,000. The statue of a woman was to have towered over the stand of honour, designed to be a full 14 metres taller than the Statue of Liberty. Then there was Speer’s pride and joy, the mooted German Stadium, designed to seat 400,000 spectators.

It only got as far as the laying of its foundation stone in 1937. The site filled with water and became the present lake Silbersee. The Luitpoldhain park was converted into the Luitpoldarena, where 150,000 members of the armed forces could march before 50,000 spectators. Today it is once again a park. Finally there was, and still is, with a few mutilations, the Zeppelin stand, with the parade ground in front of it, where in 1909 Count von Zeppelin landed in one of his airships. The stand was the work of Speer and on the parade ground 100,000 men marched past before the eyes of 60,000 spectators. It was here that the architect of the regime staged in 1937 a spectacular night show, with 130 searchlights projecting luminous beams to create a ‘dome of light’.

Leni Riefenstahl, whose ‘Triumph of the Will’ was shot here in 1934, was undoubtedly a talented director, but she was also able to count on exceptional theatrical and choreographic effects.

Today the Zeppelin stand, access to which is free, presents a depressing sight: the road below it, part of an urban motor racecourse, is normally reduced to a derelict area. And the parade ground, used for occasional musical events, looks abandoned. Further along, two ugly structures, the Frankenstadion and the ice-skating rink, turn their backs disdainfully on the existing scene and display no understanding of the place. Nuremberg, 80 per cent of which was destroyed by bombing, has proved highly skilled at the reconstruction of its historic centre, and has rebuilt its medieval street pattern, reusing original stones retrieved from the postwar rubble. Nevertheless the former Nazi propaganda compound still has no clear comprehensive design to sew back together the scattered shreds of territory and, most of all, to throw a critical light on these dark remnants of history.