Is it possible to reconcile new construction and more green space within the completed perimeter of Europe’s densest and most built-up capital? The City of Paris believes it can. After a long period of mediation within its own majority, the Parisian junta led by Mayor Anne Hidalgo has approved the capital's new bioclimatic urban plan.

The result of more than two years’ work, this comprehensive text examines all the new regulations that will govern the management of Parisian space, from housing to green spaces, transport and heritage protection, not forgetting the conditions and infrastructure for economic attractiveness. The balance between nature and the built environment is on a razor’s edge. On the one hand, it shows the willingness to increase the number of cubic metres in order to expand inclusive, social housing – already jumped from 13 per cent to 25 per cent of housing supply and now set at 30 per cent by 2035. On the other, it will mitigate climate change by expanding green areas.

Paris is not a particularly green city, that is a well-known fact. Excluding the two large parks outside the Boulevard Périférique, the ring road that surrounds and delimits the city of Paris, each citizen has only 5.8 square metres of green space, compared to the 12 recommended by the WHO. The bioclimatic plan therefore provides for a major expansion of green areas, with an additional 300 hectares to be added over the next 20 years, identified from the few plots of land still available, concentrated mainly in the north-eastern quadrant, and other private spaces (foundations or convents are mentioned) to be made accessible to all citizens. A figure considered unrealistic by political opponents, and the front of scepticism for ecologists in the same majority: during Hidalgo’s leadership, the number of hectares conquered by Parisian greenery was 30.

The proliferation of greenery is not limited to parks, but extends to all available surfaces and plots. Vegetable walls, made famous in Paris by Patrick Leblanc, will be encouraged everywhere. For every plot of land larger than 150 square metres, there is an obligation to demineralise the soil, and for plots of land larger than 5,000 square metres, 65% of the land is reserved for greenery. To compensate for this, new square metres can be gained in height. Elevation, a tool already present in the old urban plan, is increased to three storeys for modern buildings, but limited to a maximum height of 37 metres. Roofs are also included in the bioclimatic transformation, whether through the planting of new greenery, the development of urban agriculture, new solar panels, rainwater harvesting or the incorporation of sports equipment.

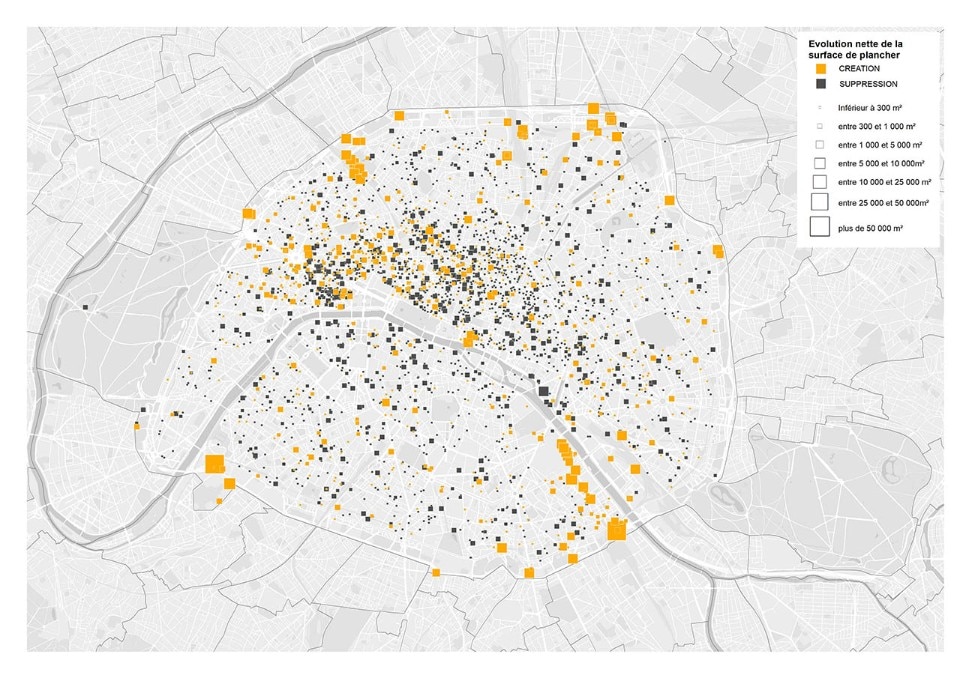

Finally, the redevelopment of office space should provide Paris with the more than 5,000 social housing units that will need to be built on an annual basis to meet the constraints of the plan. The redevelopment will favour so-called mixed-income properties: new social housing will have to be included in any residential project of 500 square metres or more. The plan is currently under review by the state legislature. If all the conditions for its implementation are met, the final vote and entry into force is expected to take place between 2024 and 2025.

Opening image: Anthony Delanoix via Unsplash