In 1946, when Domus chose the editor Ernesto Nathan Rogers, his focus was “The home of man”. After World War II, Domus focused on the urgency of reconstruction. In January 2023, “The oceanic” issue’s focus is a longer view of all life on the planet. The February issue “Questions of perception” will focus on human perception today. The March issue “Urbanisms: working with doubt” will focus on the densification of cities and simultaneously restored wildlands. The April issue “Stochastic thinking / synthesis of the arts” will be interconnected to the sciences and the crucial role the arts play in the spiritual health of humanity. The May issue “Ineffable space, immeasurable space” will drop down to the micro-scale, from the macro-scale of “The oceanic”. Thus, all five of these issues will be interconnected and celebrate the interconnection of all things.

Projects in this issue of Domus aspire to express the concept that humans are organisms that are absolutely dependent on other organisms, with a sense of art that is open, unbounded, a feeling of something limitless... the oceanic.

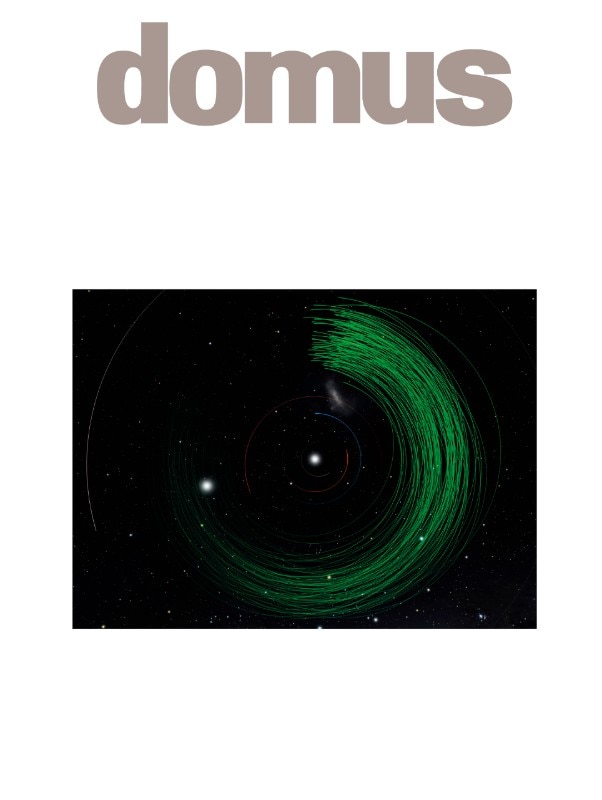

In Civilization and Its Discontents, 1930, Sigmund Freud describes “the oceanic”. He writes, “It is a feeling which he would like to call a sensation of eternity, a feeling of something limitless, unbounded, something oceanic.” As a child, my father took me ocean fishing off the Pacific Coast of Washington. I clearly remember that strange feeling when you are first surrounded by 360 degrees of empty ocean horizon. On a clear day, it is a mysterious open line of infinite space all around you. This feeling of endlessness, of timelessness and infinity – the oceanic – left an unforgettable impression. Our sense of the oceanic is being expanded today by an “infinity of infinities” in new images from the James Webb Space Telescope. Study of the cosmos reminds us of our tiny significance; particles of humanity made of cosmic dust.

The philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s 2,500-page, 3-volume Spheres is oceanic in scope. Born in 1947, Sloterdijk has attempted in these volumes to take steps beyond Being and Time, the 1927 compendium on existential thought by Martin Heidegger. What makes Sloterdijk’s project important to artists and architects is its spatial character. Sloterdijk’s argument is architectonic and moves from the micro-scale of the womb and the family in Bubbles: Volume I, to the circularity of the world in Globes: Volume II, to the macro-scale – the oceanic scale – in Foams: Volume III, which focuses on the phenomenology of community. The Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset’s statement “I am me and my circumstance” stands as the maxim for his argument that the philosopher must leave behind pre-existing beliefs and write for our time and circumstance.

Breaking free from the condition of being “inside a given fate”,Ortega y Gasset argued: “In this tied-down fate we must therefore be active, decide, and create a project for life.”Ortega y Gasset also wrote: “Imagine a city that had been built by brilliant architects who have been motivated only by the opportunity to show off their own particular style and talent... nothing but cynical, blatant, intolerable caprice...”

Theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli argues that today, the problem of consciousness “has taken the place of what in the past used to be the problem of the meaning of soul, spirit, subjectivity, intelligence, perception, understanding”. However, we as humans, without alien figures to measure ourselves against, are left only with ourselves or animals to compare to in our consciousness. Many creatures share our capacity to interact, predict, observe, communicate and perhaps to love and suffer. Rovelli writes that of the ten most important books on the nature of consciousness, number two was Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness by Peter Godfrey-Smith. This book about octopuses, those curiously intelligent inhabitants of the oceans, inspired

the recent amazing film My Octopus Teacher, a true story about a human relationship with a wild common octopus.

The study of biodiversity opens us to thoughts such as the consciousness of an octopus with its brain neurons spread across its eight arms, each of which can think. Of the great blue whale, how many are left? From 140,000 down to 5,000 or 10,000? An oceanic animal weighing 199 tons and 22 meters long, it has a heart that is 1.5 metres long and weighs 181 kilos – the largest on the planet. The poet Jim Harrison wrote, “His brain is large enough for a man to sleep in.”

O. Wilson’s work on biodiversity, which began in the 1970s, took form in his 1988 book Biodiversity, articulating the amazing natural relations between forms of life in plant and animal species. Wilson’s Half-Earth Project includes mapping the distribution of species across the globe, identifying places where humans can protect the highest number of species. In Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life, Wilson proposed “that only by committing half of the planet’s surface to nature can we hope to save the immensity of life-forms that compose it”. Wilson’s Half-Earth concept puts biodiversity in the primary driving position of any future urban theory of developing in the landscape. A human-centric theory is reversed in the Half-Earth proposal as migratory routes of biodiverse species are taken to be more important than horizontally expanded city patterns. The idea of “dense-pack” settlements and metropolitan density allows more preservation of the natural landscape and the ecosystems so important for biodiversity to be a core issue. The entirety of planet Earth’s landscapes is the focus, not the horizontal sprawl of the cities.

How can urbanists and architects embrace this “project for life”? Perhaps by creating “mini-utopias” that restore or preserve large sections of natural landscape with ecological architecture and are free of fossil fuels via geothermal heating and cooling and solar power.

In my Edge of a City projects, 1989-1991, we proposed restoring natural landscapes at the edge of American cities and building new dense-pack community settlements. Alvar and Aino Aalto, focusing on simplicity and clarity of the design of a rural house, wrote that each house is “conceived as a mini-utopia”. A new rural house standing guard, protecting several acres of natural landscape, constructed in ecological ideals (free of fossil fuels) is perhaps able to fulfil a fragment of Wilson’s Half-Earth vision with a 21st-century idealism.

Study of the cosmos reminds us of our tiny significance; particles of humanity made of cosmic dust.

In the United States, there are 34.3 million hectares of national parks and reserves, only 3.6 per cent of the land area. To achieve Wilson’s Half-Earth ideal, much more must be done. Collective efforts such as the work of Scenic Hudson have been transforming the Hudson Valley by purchasing and preserving huge sections of natural landscape since 1963. In her philosophical book The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt outlines a process in which theories are realised. This “theory of action” is one of her greatest contributions to 21st-century philosophical thought. Instead of vita contemplativa, Arendt advocates for vita activa.

The aim to articulate theories addressing our modern condition via a “theory of action” embodies ideas in new creations, a challenge to all architects, artists and designers. Projects in this issue of Domus aspire to express the concept that humans are organisms that are absolutely dependent on other organisms, with a sense of art that is open, unbounded, a feeling of something limitless... the oceanic.