The concept of public exhibitions is relatively new, starting with those of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1737 to showcase the works of painters and sculptors, followed by the Royal Academy in London with its first of many Summer Exhibitions in 1769. The heralding of the Industrial Revolution and its powerful impact on the arts was marked later by the birth of the Royal Society of Arts and its first show in London in 1761.

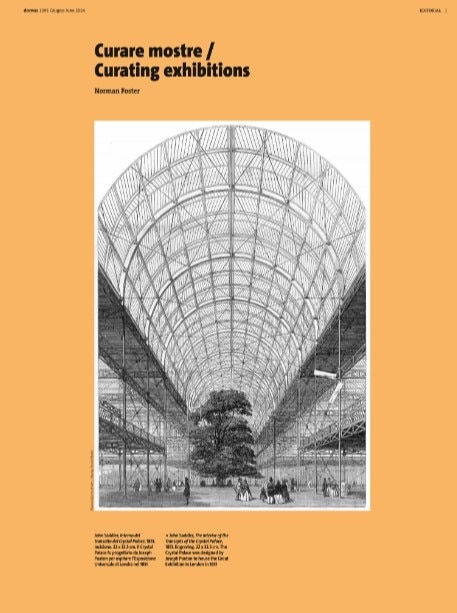

However, the blockbuster Great Exhibition had to wait until the mid-19th century with its fusion of architecture and exhibits in Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace of 1851. The construction of this mega building was as much a public spectacle as the works of industry and art from all nations that would later draw vast crowds into its cavernous interior. Such affinities between the different disciplines of art, architecture and design have long fascinated me and I find inspiration in these early flowerings of the new industrial world, which was also mirrored by the Royal Society’s mission of the “encouragement of the arts, manufactures and commerce”.

The Impressionist movement in painting of that same period, aside from a radical shift in style, was a move away from traditional subjects to those that captured the modern world. Growing up in industrial Manchester, I was equally fascinated by painter L.S. Lowry’s depictions of the barren landscapes of northern mill towns as I was by the bright new world of the future pictured in boys’ magazines of the time. They eulogised new technologies with cutaway drawings of airliners and electrified locomotives, mixed with science fiction images of the space age that was about to unfold.

At the risk of a degree of post-rationalisation, there is a likely connection, over more than seven decades, that links this youthful past to the present. One such tie is through the opportunity to curate exhibitions, where I have explored how the boundaries between the silos of art, architecture and design might be broken down – to show how they are culturally connected. This is mirrored in my practicing as an architect where I have pursued the idea of the disparate disciplines uniting together at the outset of the design process to pool their knowledge.

This team approach is the opposite of the traditional method where the architect designs the building and then feeds it down the line to the other skills. I have also embraced the inclusion of artists and specialist designers in the process. Aside from the contributions of such expertise, their creations are often inspirational. My first exhibition at Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery in 1984 juxtaposed the work of my practice with images of the Eiffel Tower, racing sailplanes, the Vertical Assembly Building and the Lunar Landers of NASA.

This team approach is the opposite of the traditional method where the architect designs the building and then feeds it down the line to the other skills.

Norman Foster

We can then fast forward four decades to Guggenheim Bilbao and the exhibition “Motion. Autos, Art and Architecture”. Here the protagonist was the automobile – 40 examples including some of the most treasured classics, others chosen for their technological innovation. If these were literally centre stage in the galleries, then they would share space with great works of sculpture and the walls around them would show the parallel worlds of the other arts – design and architecture.

One gallery contained four of the most beautiful coach-built autos from the 1930s to the 1950s, with their flowing lines reflected in Henry Moore’s bronze reclining figure with an epic Alexander Calder mobile in black and white, hovering overhead. In exploring the links between automobiles, once defined as rolling sculptures and sculpted works of art, it is worth remembering that today, even in our digital age, the bodies of automobiles are first crafted in clay as full-size originals in studios that are remarkably similar to those of artists, past and present.

A mock-up of such a studio with a team from General Motors carving away on vast blocks of modelling clay was a hugely popular attraction. In another gallery in the exhibition, I showed the visual links between the father of streamlining, engineer Paul Jaray, and sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. Jaray was a pioneering airship and automotive designer who explored the effects of speed on varying solid shapes in wind tunnels. I showed how one of his models bore an uncanny resemblance to the abstracted fish sculpture of Brâncuși.

We can be sure that they never met but culturally the affinities are very clear. This comparison links to the conversation between Brâncuși and fellow artist Marcel Duchamp when they visited the 1912 Paris Air Show together. On viewing an aeroplane propeller, they were so moved by the aesthetics of its shape that they suggested it marked the end of sculpture as they knew it.

There is a likely connection that links this youthful past to the present. One such tie is through the opportunity to curate exhibitions, where I have explored how the boundaries between the silos of art, architecture and design might be broken down – to show how they are culturally connected.

Norman Foster

The experience marked a shift that is evidenced by the later flowing and metallic works of Brâncuși. The way the Guggenheim show brought together machines and art drew a new kind of audience into the museum – people who were attracted by automobiles but who would, in any other circumstance, never step into galleries devoted to the visual arts. The record attendances showed the broader popularity of design and art once the barriers between them had been dissolved.

The most recent exhibition, at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, “Norman Foster. Sustainable Futures”, was influenced by the success of the “Motion” show. The museum’s president so liked the idea of art and designed objects being woven into the display that he opened up the main, sixth-floor gallery for the exhibition. Normally architecture shows had been confined to a much smaller ground-floor area. With the larger space, we could suspend a Libelle fibreglass sailplane alongside the Dymaxion automobile and Fly’s Eye Dome of Richard Buckminster Fuller as well as works by Umberto Boccioni and Brâncuși – all in close proximity with architectural models and drawings.

Some of the juxtapositions were literal both visually and intellectually. For example, I had made an abstracted, white, skeletal model of the structure of the JPMorgan Chase tower currently nearing completion on New York’s Park Avenue. Its setbacks and rectangular geometry are generated by the New York grid and codes. Next to this I placed one of the classic white gridded works of artist Sol LeWitt. Many visitors commented on the surprising similarities between the two works.

The link only became obvious when the accompanying caption was read. It described how LeWitt’s first job was in the office of I.M. Pei and how the artist became obsessed with the way in which the massing and setbacks of New York skyscrapers were shaped by its planning grid. Some of the works in the Pompidou exhibition dated back to my student days such as my measured drawings of the anonymous architecture of barns and windmills from the Middle Ages. Beyond the issues of heritage, there is much to learn from indigenous buildings that worked with the materials at hand.

For example, our solar-powered Masdar Institute in the desert of Abu Dhabi was only achievable by applying lessons from traditional Arabian buildings conceived before an age of cheap energy and air conditioning. In the early days of practice, after my studies, I sought out references on the subject of indigenous buildings and the most important one that I discovered was Architecture Without Architects by Bernard Rudofsky. Further research led me to discover that it was originally the catalogue of an exhibition he curated at New York’s MoMA in 1964. Sometimes an exhibition can have a ripple effect far beyond its original ambition.

Opening image: Norman Foster in front of a work by Gerhard Richter at the exhibition “Moving: Norman Foster on Art”, Carré d’Art, 2013© Nigel Young / Foster + Partners