All the systems that make our world work are made of metal. Our energy and industry infrastructure, power lines, production plants, warehouses and data centres are light metal enclosures around arrays of metal machinery. The global supply chain is propelled by fleets of ships, trains and trucks of steel.

Planes and rockets are forged and finished from powder-coated aluminium, with the exception of the Starship with its signature stainless steel silhouette. The iconic white panels and black ceramic of the Space Shuttle inspired Star Trek’s and Star Wars’ visions of a future consisting of endless interior environments of white powder-coated metal panels.

Modern life is sustained by a back of house made of metal. In this April issue it takes centre stage.

Bjarke Ingels

The everyday metals of the world come in incredible textures and hues, coatings and alloys: raw, sandblasted, brushed, vibrated, galvanised, stainless, anodised, oxidised, chromatised, hot-dipped, weathered, hot-rolled, cast, extruded. But due to fire resistance and weatherproofing, their material presence tends to be reduced to an arbitrary coat of paint.

Historically, metals made their way into tectonic culture in the form of jewellery, then weaponry and finally tools and technology. The aqueducts of the Roman Empire were lined with lead, leading to speculations that lead poisoning may have been the main cause of the decline and fall of Rome.

In architecture, metals were reserved for the adornment of spires and roof finishes. The zinc roofs of Paris, the copper spires of Copenhagen. Industrialisation scaled up the access to and affordability of cast iron, and manufactured steel – propelled by the steam engine, steel tracks and bridges – inflated the size of steel structures to the building scale and beyond. One of the world’s most significant architectural landmarks is a steel structure designed by a railroad engineer, Gustave Eiffel.

Four years later, George W.G. Ferris Jr. an engineer in direct competition with Eiffel, built The Ferris Wheel for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. The fair was nicknamed the White City, because the architects were still occupied with arbitrary choices of ornaments and finishes even if underneath the white plaster, the bones of the buildings were beginning to transform with skeletons and ducts of steel, cables and pipes of copper.

If Corbu was the advocate for the ascension of concrete from brute to beautiful, Mies van der Rohe was the mind behind the apotheosis of steel. The son of a stone mason, his work saw the role of stone reduced to adornment, leaving steel for structure and glass for facades. In a reductionist journey from Villa Tugendhat (1930) to the Farnsworth House (1951), Mies gradually distilled the house down to its skeletal essentials – steel bones wrapped with a skin of glass.

The tectonic end game of a journey culminating in seminal works like Crown Hall (1956) and the Neue Nationalgalerie (1968), where you could almost argue that the entire architectural intent is present in the shop drawings from the steel engineer. a prototype for a universal building, which he later twinned at The Seagram Building (1958) and he kept cloning across the North American continent, keeping an I-beam like an idol on his desk by his death.

In post-war Los Angeles, a group of young architects explored the industrial catalogue of building products as the ingredients of a new postwar vernacular with their Case Study Houses (1945-1966). The Eames House (1949) is essentially a light steel shelving system with customisable facades and wall materials. Home order catalogue turned actual home.

In this issue, we have chosen to explore the variety of material manifestations of the two most common workhorses of the construction industry: aluminium and steel.

Bjarke Ingels

For me, the discovery of steel as a building material started with the Centre Pompidou (1977) by Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. The idea of a building turned inside out. All the necessities of modern human existence freed from the constraints of the poché and exposed on the outside like colourful decor. Rogers’ Lloyd’s Building (1986) continues down this path, stripping away the final coat of paint to reveal the undeniable beauty of the stainless steel alloy.

Herzog & de Meuron’s use of copper roof as a facade material for their Signal Box series (1994-1999), or RCR’s use of untreated raw steal or Enric Miralles’ use of welded I-beams and raw rebar gradually opened my eyes to metal as a rich material with potential for patina and poetry way beyond the powder-coated perfection of the sci-fi of my childhood.

In this issue, we have chosen to explore the variety of material manifestations of the two most common workhorses of the construction industry: aluminium and steel. Junya Ishigami explores the role of steel in his pursuit of almost ethereal immaterial lightness. Gerard Barron of The Metals Company is collecting polymetallic nodules from the oceanic abyss for the materials to enable our global energy transformation, free from the social and environmental tailings of conventional resource extraction.

Dominique Perrault, the grandfather of metal fabric as architecture, has created a 2,300-page tome in celebration of metallic textile. Barozzi Veiga’s Dynafit is a corporate HQ turned public monument composed of two juxtaposed triangles of metal and glass. SO-IL has turned the objet trouvé of Brooklyn zoning regulations into a bundle of translucent towers wrapped in perforated anodised aluminium. TAOA has reduced the building facade to a monolithic object under a veil of perforated corrugated anodised aluminium. Gustav Düsing and Max Hacke have turned warehouse-like modular flexibility into a generous and dynamic space.

Carmody Groarke has boiled the roof down to the fundamentals by stacking sheets of aluminium like a house of cards on top of an old townhouse. Atelier Deshaus has dissolved the building into a swarm of steel sheets, while KWK Promes has turned content into form with their tubular steel architecture for a pipe distribution company. Trahan Architects explores Corten steel in its raw and muscular form, while DaeWha Kang Design has turned architecture into an inhabitable form of stainless steel jewellery. MAD’s stainless steel Tornado is like the material manifestation of a computer-generated dream. Like architecture as frozen music, MAD’s work is like the meticulous materialisation of motion graphics.

Sam Chermayeff takes the contemporary vernacular of gas burners, cooktops and kitchen appliances and composes them like effortlessly scattered furniture, dissolving the straitjacket of their modern monolithic kitchen complex. Muller Van Severen celebrates the everyday elegance and slenderness of aluminium tubes, brass sticks and lacquered steel in their collection of everyday objects oscillating between minimalism and expressionism. Turning the obligatory coat of paint into an exquisite sensibility. Generic as a form of iconic.

Ben Storms explores steel as a raw substance, while Sizhu Li explores the mechanical attributes of coiled sheet steel. And Ahmed Mater reveals the almost divine forces of magnetism in his material recreations of the impact of religious ideas on human organisation. Lastly, as our monthly oxymoron, Antony Gormley tells us how he recasts iron scraps in rigid geometries to capture the sensuality and vulnerability of the human form.

All are testimony to material practitioners devoted to exploring the unique attributes of aluminium and steel, once you reveal it from underneath the ubiquitous layers of fire, paint and sheetrock. Modern life is sustained by a back of house made of metal. In this April issue it takes centre stage.

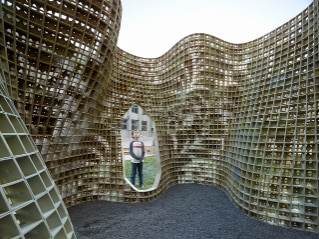

Opening image: Interior of CopenHill, the waste-to-energy plant topped by a ski slope designed by Bjarke Ingels Group in Copenhagen, 2019. The plant's continuous facade features aluminium boxes measuring 1.2 m high and 3.3. m wide, stacked like large over lapping bricks. Photo Seren Aagaard