In the language of the Pharaohs, artisans and artists are identified with the term kathemut, in which kat indicates the working of materials, and hemut the person who works with materials. In Greek, (τεχνίτης) technìtes, in Latin artifex: the artist-artisan, protagonist and narrator, combines and characterises, influencing and contaminating culture with method and style.

“There is no essential difference between the artist and the artisan [...]. So let us therefore create a new guild of craftsmen, free of the divisive class pretensions that endeavoured to raise a prideful barrier between craftsmen and artists”. So claimed Walter Gropius in his manifesto for Bauhaus in 1919.

A complex series of historical and aesthetic questions surround these two figures, now set apart, once equal and on the same level, who have, over the course of the centuries, developed both an art defined as “fine”, such as painting, and a form of art that is currently defined as applied, previously industrial, or – more dismissively – perpetuating a deep-rooted incomprehension, “minor”. Their definition is a question of culture.

In these light, an examination of the fine interweaving between art, architecture and design, and therefore between artisans and artists, allows an understanding of their reciprocal relationships and close ties, in terms of influences, that carry the echo of the continuous relationship between all the related disciplines over the course of the centuries. A century ago saw the foundation of the Institute of Art Education that remained open for just 14 years, but in that time left an important mark on everything that surrounds us; Bauhaus. Here, the debate finds fertile ground. From William Morris, who protested of the mediocrity of industrial design, championing the rebirth of the artisan by founding a production centre, Arts and Crafts, to Gropius, who maintained the exact opposite. Then, much later on, in Italy – soon after the end of the Second World War – design was to emerge, thanks to the coming together of artists, architects and artisans, who in direct and close collaboration created and produced a perfect fusion of all the arts, and most significantly in all fields of art.

In these light, an examination of the fine interweaving between art, architecture and design, and therefore between artisans and artists, allows an understanding of their reciprocal relationships and close ties

Conceptualised by important forefathers such as Ponti, Albini or the Castiglioni brothers, Italian production made an important impact on the market, even today maintaining its dominance thanks to the idea of maintaining, elaborating and transfiguring classic tradition. “The formal world in which we live is much richer that the ancient world, because it also includes those past times. In our culture, antiquity is a ‘contemporary’ concept. In culture, the ancient does not exist; what exists is the simultaneous and wonderful presence of every ancient and contemporary thing, and the mysterious attraction of the future”. This according to Gio Ponti, the founder of Domus who, as Mario Sironi did with painting, identified and maintained a classicality in his art that never went out of fashion. In the most well-known series of ceramics, such as Le mie donne and Conversazione classica, his taste for sophisticated references is evident. In the first case the artist drew inspiration from classic Renaissance decorated plates, which depicted strong and elegant female figures, similar to those in the style of Michelangelo found in the Sistine Chapel, while in the second case he looked to the Grand Tours of the Eighteenth century, describing the figures of travellers enamoured with Italy.

Ponti combined the old with the new, drawing from the Greek, Etruscan and Roman worlds, as well as a vast figurative repertoire of Palladian and Neo-classical origin. Similarly, the Castiglioni brothers, with their Arco lamp, also looked to the past, making a clear reference to classic architecture and the perforated dome of the Pantheon.

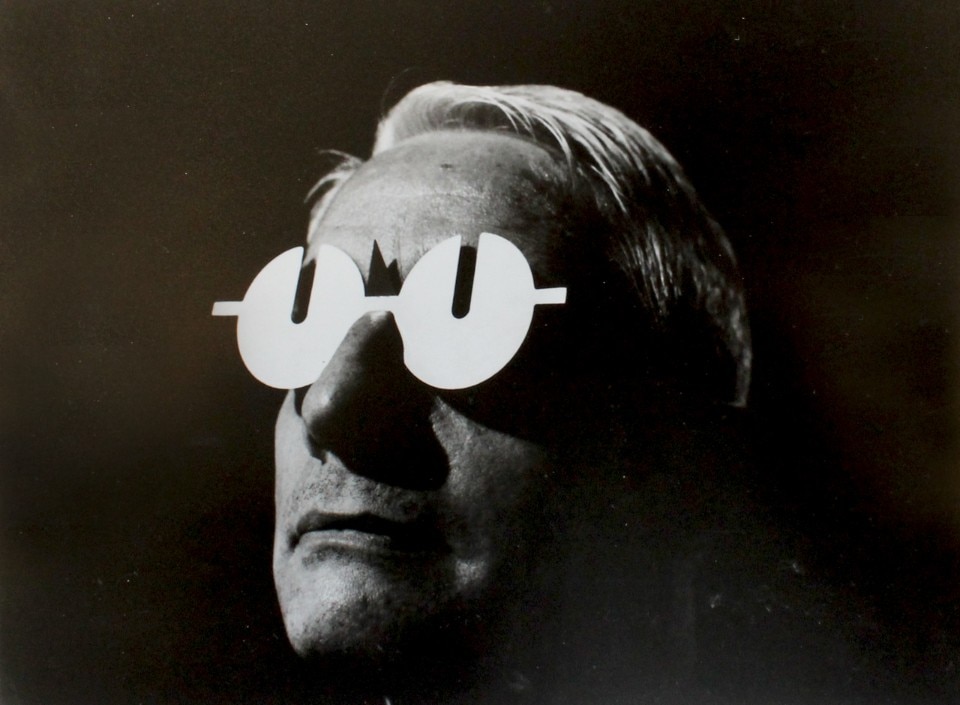

However, there are also more contemporary and surreal citations. Eccentric and bizarre objects, created with the aim of transforming everyday objects into works of art of an extravagant nature, such as the Mae West sofa by Salvador Dalí and the mocking sculptures of Meret Oppenheim, or the Proust armchair by Alessandro Mendini, can perhaps recall the baroque seats depicted in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century portraits. Similarly, there are chairs that make clear reference to artistic movements such as impressionism, pointillism or divisionism. So, can the artisan and the designer be considered exponents of “fine” art? That art and inventiveness that only the great artists were capable of? Or are these simply revisitations of pre-existing objects, where decorative or structural elements were added, modifying the dynamics of the original?

Literary references, pictorial citations, the work of skilful artisans. All of this probably leads to the creation of a “different” form of art, but certainly not one that is less noble, or minor

In short, literary references, pictorial citations, the work of skilful artisans. All of this probably leads to the creation of a “different” form of art, but certainly not one that is less noble, or “minor”. An idea, an inspiration, immediately followed by creation. This is undeniably art, or rather Art, with a capital ‘A’. “The artist is a receptacle for emotions that come from all over the place: from the sky, from the earth, from a scrap of paper, from a passing shape, from a spider’s web.” This from Picasso, who added: “Good artists copy, great artists steal.”

Opening image: Sala Mae West of the Teatro-Museo Dalí de Figueres, Girona. Photo Lanoel.