The stark difference between Denis Villeneuve’s Dune films and HBO’s new series, Dune: Prophecy – airing on Sky in Italy – can be traced directly to the credits. The series’ production design is led by Tom Meyer, whose résumé includes a string of sci-fi and superhero projects marked by rather generic and forgettable aesthetics.

By contrast, Villeneuve’s films benefit from the genius of Patrice Vermette, the director’s longtime collaborator and the creative force behind the remarkable design of Arrival. The series fares no better with its concept artist, whose previous work on Christopher Nolan’s Tenet was equally underwhelming in design. Villeneuve’s Dune, in contrast, drew on the talents of concept artists from Blade Runner 2049, a visually groundbreaking masterpiece.

Although produced by HBO – arguably the gold standard for American television – the visual identity of Dune: Prophecy feels more like a mishmash of HBO’s existing productions than a genuine extension of the Dune universe. The cinematic adaptations of Dune derive much of their power from their aesthetic and design, a strength the series fails to replicate, stumbling right out of the gate.

HBO’s monumental success with Game of Thrones is clearly reflected in Dune: Prophecy, influencing everything from its pacing and narrative structure to its depiction of rival families and political intrigue

Set 10,000 years before Paul Atreides’ story (brought to life by Timothée Chalamet in Villeneuve’s films), Dune: Prophecy explores the creation of the Bene Gesserit sisterhood, a mystical order tasked with cultivating and safeguarding spiritual power. On paper, it’s a story ripe with intrigue – power struggles, conquests, and the seeds of a grand mythology. Yet in execution, the series seems to take its cues more from Game of Thrones than from Frank Herbert’s richly imagined world – and not by chance.

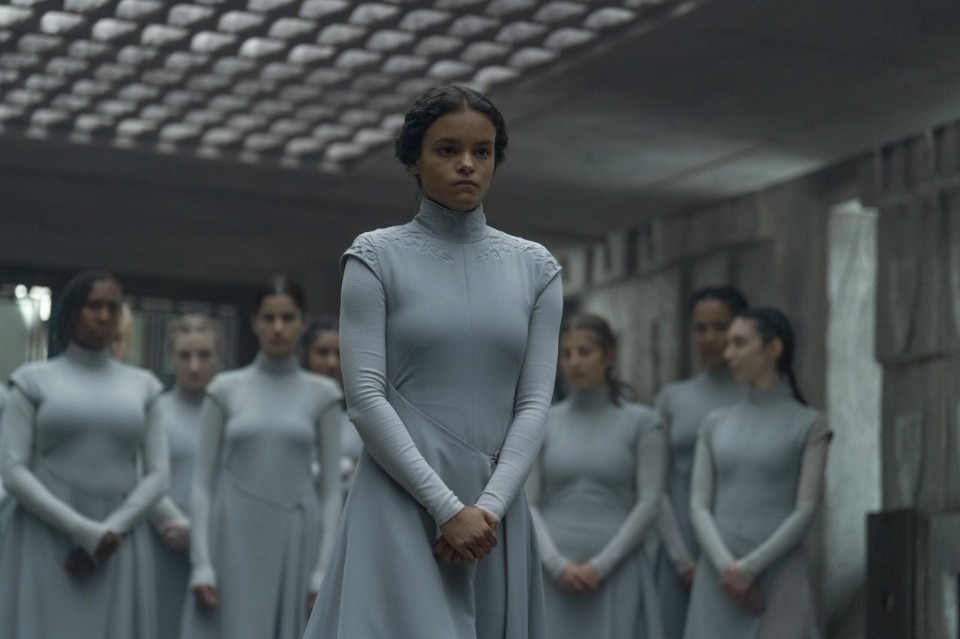

HBO’s monumental success with Game of Thrones is clearly reflected in Dune: Prophecy, influencing everything from its pacing and narrative structure to its depiction of rival families and political intrigue. Much like House of the Dragon, the Game of Thrones prequel, Dune: Prophecy feels shaped to replicate a proven formula. The series even adopts a medieval aesthetic that clashes with the futuristic mysticism central to Frank Herbert’s universe. While the show occasionally borrows sci-fi elements – color palettes, cavernous barren interiors, and dimly lit spaces evocative of the films – to draw in the large audience familiar with Villeneuve’s movies, it ultimately fails to create a world that feels truly alien or futuristic. Instead, the aesthetic leans heavily into the past, feeling rooted in medieval tropes rather than the otherworldly.

The narrative excuse is simple enough: it’s a prequel, set in the distant past of the Dune universe. Even so, it’s still a science fiction story, one that rarely recaptures the genre’s distinctive flavor. The costume design, for instance, oscillates between being a derivative of the films and veering awkwardly toward fantasy. This aesthetic decision ripples through the series, shaping everything else. At its core, science fiction explores the tension between matter and spirit: how, in a technologically advanced or regressed future, the human spirit struggles to avoid being stifled by materialism. This conflict plays out through technology, dictatorships, systems of control, or even destruction caused by technology that reshapes society’s mindset.

In Dune: Prophecy, though the story unfolds in the aftermath of a technological catastrophe – a war against the machines – this backdrop is barely addressed. Villeneuve’s films, by contrast, masterfully bring to life the novels’ extraordinary fusion of mysticism, militarism, and technocracy. In Paul Atreides’ tale, the world is visually and narratively suspended between the extremes of highly advanced technological progress and profound spiritualism, between the forces of mind control and technological dominance.

The first movie opens with a high-tech assassination attempt on Paul, thwarted by his premonition, and follows with a mystical test suggesting his superhuman potential. And, of course, there are the ever-looming sandworms – creatures that are either subdued through technological means or tamed by human skill.

Dune: Prophecy delivers none of this. Like many serialized shows, it relies heavily on language and dialogue – but without the gravitas or poetic weight of Game of Thrones. It fails to recreate the classic logical tensions that define the Dune universe, whether in its story or design. For instance, while the emergence of “the Voice” – a psychological technique allowing control over others – is depicted, it lacks a technological counterpart to balance it. Space and starships appear, but the spiritual dimension is conspicuously absent. Instead, the series falls back on familiar tropes: political intrigue, poisonings, and the typical mystery characters whose identities and purposes are unclear yet who wield inexplicable power. This overused device – common in Game of Thrones and Westworld – makes these figures feel less like rebels from a futuristic world and more like mountain barbarians misplaced in a sci-fi setting.

The costume design, for instance, oscillates between being a derivative of the films and veering awkwardly toward fantasy.

David Lynch’s ill-fated Dune (1984) was a great failure, but it remains a benchmark for visual creativity. Lynch crafted a future steeped in steam and brass, a fusion of metal and flesh, grime and sweat – offering a visceral counterbalance to technological grandeur. Though hampered by a troubled production, the film was beautifully conceived, with scenes that remain striking even today. In comparison, Dune: Prophecy lacks this level of ambition. The series had the advantage of learning from Villeneuve’s movies, which set a high standard for merging mysticism and militarism with breathtaking design. Yet the TV medium’s industrialized production process seems ill-equipped to match such sophistication. The fact that Denis Villeneuve, who is listed as a producer, has in fact stepped away from the production speaks volumes.

If Dune: Prophecy teaches us anything, it’s that even the most celebrated narrative cycles, meticulously crafted worlds, or iconic brands are nothing without a compelling visual identity to anchor them and give them credibility. In science fiction, design isn’t just decoration – it’s the difference between suspending disbelief and losing it entirely. Inventing a future involves more than imagining events or mythologies; it requires envisioning the trajectory of society itself, brought to life through objects, architecture, transportation, materials, and the interplay of light. The world of Dune: Prophecy feels hollow, its vision of the future unconvincing, flavorless, and above all, aesthetically barren. How can anyone be captivated by so little?