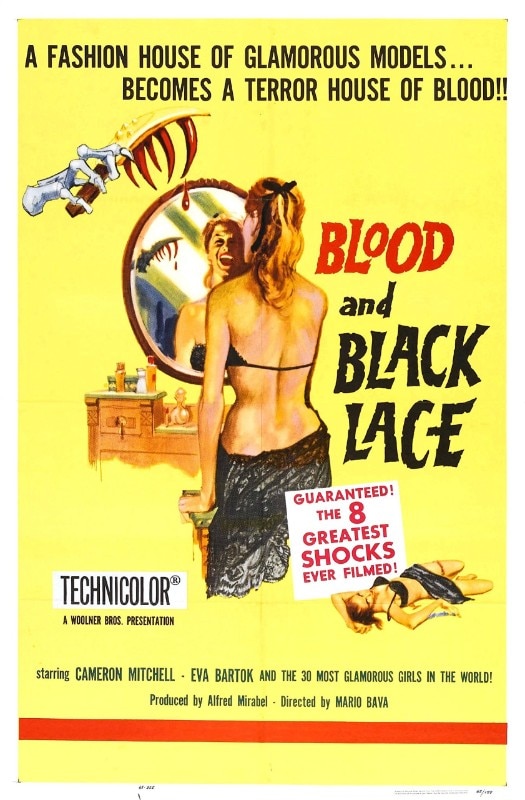

In 1964, the Italian giallo officially arose with Mario Bava’s Sei donne per l'assassino (“Blood and Black Lace”). With this film, Bava established the defining conventions of the genre and all the rules that would be emulated in other movies. Remarkably, it wasn’t a commercial hit. Instead, it was an artistic triumph that, by leveraging its bold visual style, influenced other directors in the thriller and crime film scene, first in Italy and later worldwide.

“Blood and Black Lace” is a unique masterpiece of style and design, both completely distinct from any other 1960s Italian giallo films and at the same time the genre’s origin point. Directed by Mario Bava and written by Marcello Fondato, Giuseppe Barilla, and Bava himself, designed to be an aesthetic exercise, “Blood and Black Lace” tells the story of a series of murders set in the world of fashion.

Unlike many other Italian thrillers and crime films of the time, which were often brutal and quite direct, “Blood and Black Lace” takes a more subtle yet firm approach in captivating the viewer, attacking and catching them. Yet nearly every subsequent film in the genre aimed to capture something of its groundbreaking style.

The film’s most notable features – and in a sense its true essence − are its masterful use of color, costume design, and cinematography. Every frame is visually meticulously composed through its cinematography, subtle camera movements, and sequences.

Bava’s film is a radical visual experiment, showcasing the beauty within horror and the style withing a murder case – with all its blood and savagery – which exist in an almost oneiric state. Watching it today, the film doesn’t seem set in reality but in a suspended, ethereal universe, in which things – just like in dreams – are suggested, distant, and exist only since logic gives way to emotional impact.

Blood and Black Lace is a unique masterpiece of style and design, both completely distinct from any other 1960s Italian giallo films and at the same time the genre’s origin point.

Recently, “Blood and Black Lace” was restored by the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia. To commemorate this occasion, a dossier was published, featuring contributions from critics, directors, and industry professionals who worked on the restoration and were close to Bava. Among these is a piece written by Dario Argento, Bava’s greatest disciple. Here’s the full version:

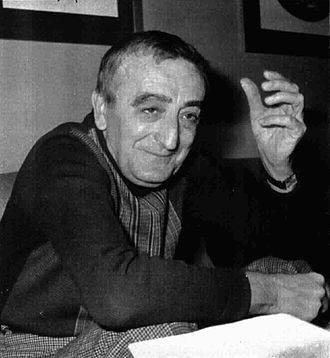

“My cinema is new compared to what had been seen up to that point. The film directors who inspired me are Fritz Lang and Alfred Hitchcock, and I also have great admiration for Godard. Among Italian filmmakers, I always paid close attention to Mario Bava’s work, as no one else possessed his skills from a visual perspective. “Blood and Black Lace” uses color in an extraordinary way; it is a perfect film. In fact, I later asked Mario Bava to collaborate on some of my projects and I produced his film “Shock,” staring Daria Nicolodi. Once again, he demonstrated his ability to create miraculous effects with minimal financial resources. Bava was a true craftsman; he could invent anything while meticulously respecting the budget he was given. While “Blood and Black Lace” may not have a particularly special story, the images it portrays are extraordinary − no one had achieved such a level of visual artistry before. Interestingly, both Bava and Hitchcock faced the same derogatory label of being “skilled craftsmen.” And Bava was one, indeed. At the highest level. His work deserves reevaluation; it is a task that Italian critics should finally undertake. Mario Bava is recognized worldwide as one of the masters of our cinema, yet in Italy, perhaps due to foolish provincialism or superficial political intrigues, he is often dismissed as merely a skilled craftsman struggling to gain recognition from producers. It is an implausible situation.”

Among the many innovations in “Blood and Black Lace,” the most iconic is likely the portrayal of the killer. Dressed in black, with a leather hat and gloves, he wears a mask that obscures his face, and the viewer often witnesses the killer’s actions through his eyes, as if they were him. He embodies the archetypal Italian giallo murderer, a character that has been echoed by filmmakers − Dario Argento first and foremost − not just in Italy but globally.

Every mask worn by a killer ever since can trace its lineage back to this movie. As director Paolo Strippoli notes in the dossier, at the end of the sixth murder, the victim removes the mask from the killer just before dying, yet we still do not see his face − much to our frustration. This same technique is echoed in the first murder of Wes Craven's “Scream,” featuring another masked killer.

The restoration of “Blood and Black Lace” is one of the most significant of the year, not only due to the film's importance in the history of cinema but also because its core theme and visual research are centered on splendor. Bava was an exceptional film technician, having started as a cinematographer and possessing a profound understanding of the medium.

Bava was a true craftsman; he could invent anything while meticulously respecting the budget he was given. While “Blood and Black Lace” may not have a particularly special story, the images it portrays are extraordinary.

Dario Argento

Here, he experiments with something radical − not in terms of ruthlessness or gothic themes (though those are important in his work, starting with “Black Sunday”), but rather in forging a new relationship between low themes, like tales of bloodshed, and more elevated ones, like beauty in the classical sense, that of compositions influenced by paintings, graphics – and, of course, fashion. This created something entirely new: a thriller that does not simply aim to imitate reality but seeks to idealize the instincts that comprise it, the tension and latent eroticism inherent in murder.

The Pipe collection, between simplicity and character

The Pipe collection, designed by Busetti Garuti Redaelli for Atmosphera, introduces this year a three-seater sofa.