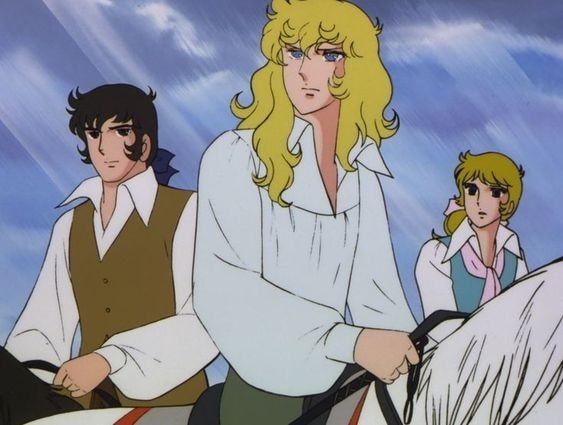

Over fifty years after the debut of one of the most famous shoujo manga series, Lady Oscar is set to return to Japanese cinemas in the spring of 2025 with a highly anticipated new film, The Rose of Versailles – a direct translation of the original title Berusaiyu no bara. This release celebrates the 45th anniversary of the original anime, which first aired in Japan in 1979 and later made its way to the West, where it was partially censored.

With her androgynous appearance, Oscar moves, fights, and commands like a man, proving herself the best in the palace. Yet her physical and moral superiority is often unacknowledged.

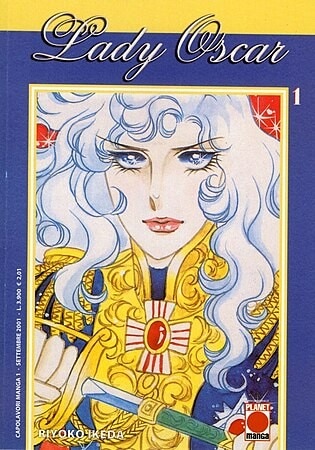

Riyoko Ikeda: a pioneer in shoujo manga’s renewal

Like Lady Oscar herself, Ikeda had to navigate the challenges of being a woman within the leftist movements of 1960s Japan. A socialist and feminist with a philosophy degree, specializing in Marx and Lenin, Ikeda infused her work with themes of class struggle, revolution, and anti-authoritarianism – shaped in part by her own family background (she was born to an aristocratic mother and a middle-class father, and her marriage was initially opposed by her mother’s family).

Her work blossomed during the last decades of the Shōwa period (1926–1989), an era that was still conservative and resistant to women’s independence. It was also a time when manga experienced a renaissance thanks to the Group of 24 – a collective of female mangaka, born around 1949, with whom Ikeda is often associated. These authors revived the genre, tackling political and gender issues largely untouched since the 1920s, and often focusing on heroines who grew up in harsh conditions, fighting for their happiness from an early age. Riyoko Ikeda, with Lady Oscar, was at the forefront of this revival. Through The Rose of Versailles, she delved into the history of the French Revolution while also encouraging Japanese women to embrace personal liberation through radical movements.

Queerness, class struggle and feminism: a revolution in the making

The story is well-known: Oscar François de Jarjayes is a young woman raised as a man by her father, General Reynier de Jarjayes, who was disappointed not to have a male heir to carry on the family’s military legacy. Set against the backdrop of the French court in the late 18th century, Oscar becomes the commander of the Royal Guard, serving Princess (and later Queen) Marie Antoinette. The narrative follows their perspectives as they witness the events leading up to the French Revolution.

In Lady Oscar, revolution is a central theme, subverted in various ways. The palace of Versailles is described in meticulous detail, yet the characters who inhabit it are not bound by the same realism, allowing the audience room for imagination and identification. The series challenges traditional gender roles, flipping conventions: women drive the narrative, while the male characters take a back seat.

With her androgynous appearance, Oscar moves, fights, and commands like a man, proving herself the best in the palace. Yet her physical and moral superiority is often unacknowledged. Her bold, self-assured exterior is balanced by a deep inner struggle – an identity crisis rooted in her gender incongruity. This allows readers and viewers to explore queer possibilities and desires within an alternative space. Oscar symbolizes resistance against the trauma and violence that nonconforming individuals often endure, both physically and emotionally, particularly in relation to the domestic and familial sphere. Even the Italian version of the theme song – which, unlike the original, explains the story more explicitly – bluntly sums up Oscar’s existential discomfort in its opening lines: “The good father wanted a boy, but alas, you were born.”

Ikeda’s analysis also incorporates reflections on social inequality and class struggle. The setting of pre-revolutionary France, where growing discontent among the populace mirrors the widening gap between rich and poor, serves as an effective narrative tool for addressing these issues.

Oscar symbolizes resistance against the trauma and violence that nonconforming individuals often endure, both physically and emotionally, particularly in relation to the domestic and familial sphere.

Oscar’s inner conflict also stems from her aristocratic background. Raised among the elite, she becomes increasingly aware of the injustice in society. Her proximity to Queen Marie Antoinette and the court allows her to witness both the suffering of the common people and the stark inequality within the system. This awareness ultimately leads her to reject her privilege and join the revolutionary cause. Oscar dies during the storming of the Bastille – a symbolic moment marking the beginning of the French Revolution.

Her liberation coincides with a personal revolution: she sheds the constraints placed on her by society, embraces her identity as a woman, and reciprocates the love of André Grandier – her loyal servant and childhood friend – while standing with the oppressed in the fight for justice.

Riyoko Ikeda’s legacy, both politically and culturally, continues to resonate, influencing generations of artists and readers alike. Lady Oscar’s flowing blonde hair and inner strength have solidified her place as a modern-day Prince Charming.

Lady Oscar in 2024: a timeless icon

Lady Oscar embodies revolutionary themes that remain powerfully relevant today: gender dysphoria, queer exploration, social inequality, and the internal conflict that arises from the disparity between one’s inner self and societal expectations. For Japanese girls in the 1970s, and later adolescents around the world, Lady Oscar offered a tale of rebellion and the validation of personal fantasies, traumas, and desires for self-discovery.

Since its initial publication in 1972, The Rose of Versailles – the original title of the 14-volume manga – has achieved global success, spawning an anime series and multiple adaptations, including musicals, films, and an upcoming feature-length animated movie.

Through Lady Oscar, Riyoko Ikeda rewrote the rules of shoujo manga, which traditionally targeted young female audiences. She introduced a heroine with a complex emotional landscape, who shattered stereotypes and expanded the boundaries of what “literature for girls” could be.