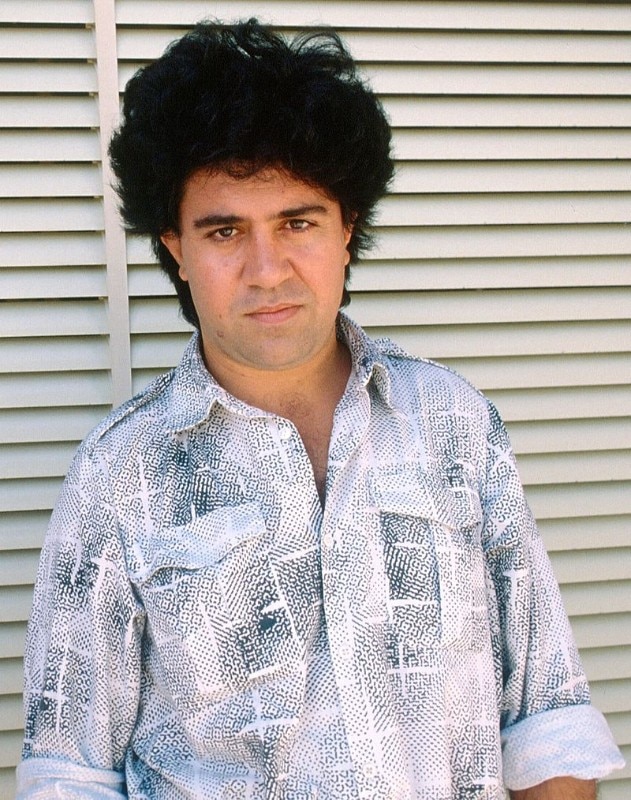

Before Pedro Almodóvar, there was no one in Spain – and perhaps in the world – who could connect the underground movida cultures that surged after Francoism with a mainstream audience. With Pepi, Luci, Bom and the Other Girls on the Heap, his debut feature, Almodóvar began using commercial genres – particularly comedy, but also thrillers and detective stories – to explore other people, other genders, and other sexualities that had been suppressed by the dictatorship and confined to punk subcultures at the time.

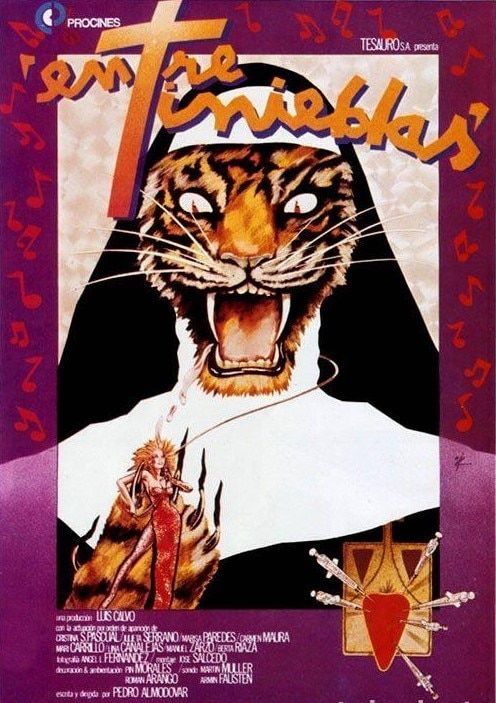

That’s where he came from – or rather, before that, he came from the deeply Catholic world, raised (or misraised, as he would admit) by ignorant priests. No one ever taught him how to make films. His early work was rough, filled with distortions and rawness, but there was an energy to it that can’t be taught. His third feature, Dark Habits, tells the story of a nightclub singer who seeks refuge in a convent of increasingly eccentric and transgressive nuns. His fourth, What Have I Done to Deserve This?, is a brilliant satire about a repressed housewife freed by new friendships and a young girl with telekinetic powers. These films are full of grotesque commercialism, sex, and vulgarity – and they are hilarious.

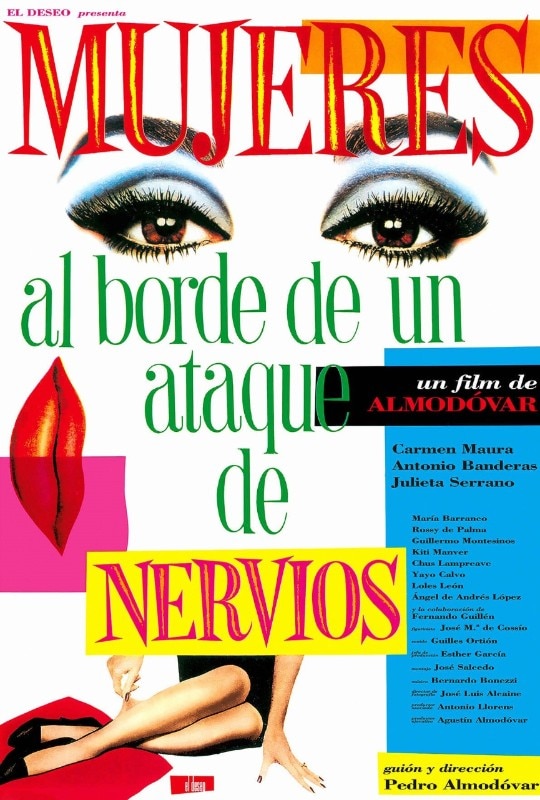

By 1988, with Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown – his seventh film – it was clear that Almodóvar had honed his skills as a director. He had developed an aesthetic of vivid colors, fluid camera movements, and rich references to painting, theater, and literature, all of which are still his trademarks. This is his most fully realized comedy, with a nod to Jean Cocteau’s The Human Voice, blending drama and laughter in a way that radiates femininity. Women – liberated from the male gaze – showcase their femininity, laughing and crying over what he calls “women’s stuff.” It’s a manifesto of sorts.

Almodóvar populated his films with unconventional physiques and faces, as well as country women, grandmothers, mothers, daughters, and free-spirited girlfriends – people who were rarely given depth on screen.

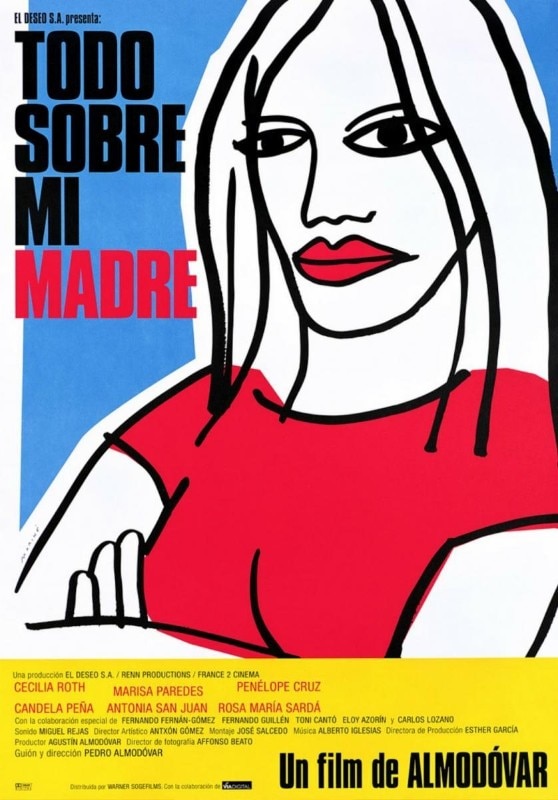

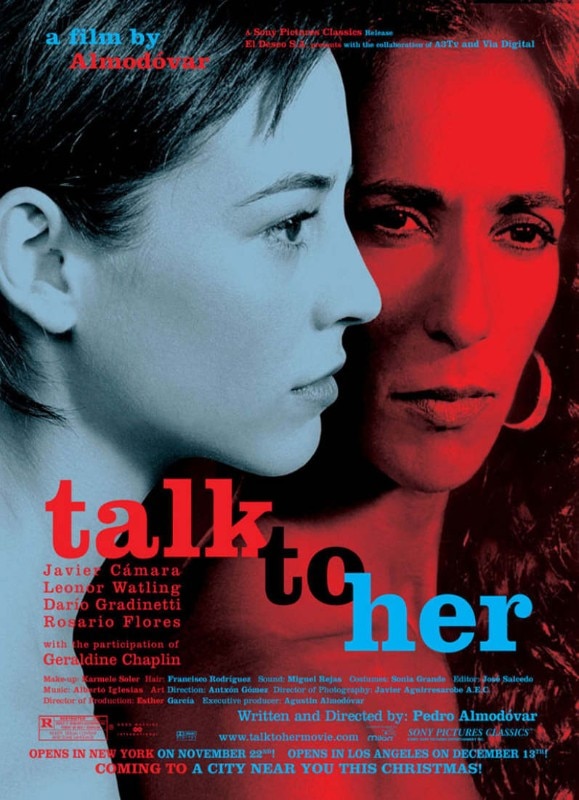

The 1990s were his years of commercial success. With films like Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! – the story of a stalker who kidnaps a woman so she’ll fall in love with him (and of course she does… it is Antonio Banderas, after all) – and melodramas like High Heels, The Flower of My Secret, and Live Flesh, Almodóvar cemented his place among the greatest living directors. This era culminated in All About My Mother, the sum of everything he had become as an artist. His next film, Talk to Her, would only solidify his standing. By then, he didn’t need to make people laugh anymore – he had mastered making them cry.

For the first time, these wildly successful films brought homosexuality into the mainstream – gay characters weren’t relegated to the background but instead engaged in explicit sex on screen (something previously unseen in commercial cinema). His films also featured transsexual characters – played by trans actors – who explained the challenges of surgery and the struggle to reshape one’s body. Almodóvar populated his films with unconventional physiques and faces (Rossy De Palma could only have become an actress in an Almodóvar film), as well as country women, grandmothers, mothers, daughters, and free-spirited girlfriends – people who were rarely given depth on screen. Almodóvar's great achievement as a filmmaker was developing a style, a sensibility, and a touch that brought taboo subjects – homosexual desire, transsexual experiences, unconventional obsessions – into the homes and conversations of conservative audiences (in Talk to Her, he even depicts the rape of a corpse). He introduced viewers to this new world, all while wrapping these provocative themes in the package of romantic melodrama.

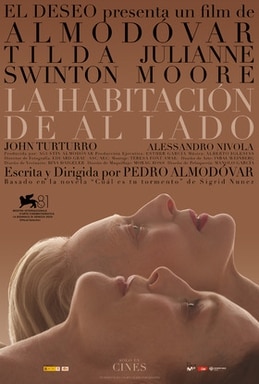

In the 2000s, his momentum seemed to slow. Almodóvar faced physical challenges, and his films became slower and more repetitive. But recently, Pain and Glory reignited his passion for storytelling, tapping into new ideas and fresh taboos: aging, death, and the end of everything. One of the most vital and exuberant filmmakers now grapples with decay and mortality, reflecting on it all with extraordinary sensitivity, optimism, and a lust for life. He injects his signature color and joy into the contemplation of death. His latest film, The Room Next Door, which premiered in Venice, is a story about euthanasia and coming to terms with the world’s end due to climate change. It’s a bleak and desolate premise, but, as always with Almodóvar, it’s infused with vitality and passion. Even the taboo of losing a loved one is transformed into an extraordinary scene that blends Bauhaus with Edward Hopper – a painting come to life in the most beautiful moment of the film. For Almodóvar, the passing of life isn't a defeat, but rather, a triumph in the transition. Only he could pull this off.