The end of the year, a time for evaluations. And an excellent opportunity to be surprised by what has happened in the last twelve months. Between great confirmations and unexpected results, that’s what happens when you look at the list of articles published on the Domus website that you, dear readers (or as it is often said in the digital context, “users”), have liked most here (increasingly through direct access to the homepages) or on our ever-expanding digital platforms, on our social media, or in one of our newsletters, to which you can subscribe here.

This shortlist of articles is dominated by “collections,” or articles that bring together several examples of the same type. And there is something for everyone, from infrastructures (train stations), to the dense archive piece on the 50 most important houses ever published in Domus in its almost 100-year history, to fashion (sneakers), to abandonment, almost in a nostalgic leap towards the 90s, to the weird (weirdest skyscrapers), a category that dominates in every field of knowledge and entertainment.

There is, of course, Brutalism, which has gone from a niche phenomenon to a ubiquitous social media trend. But there’s also room for films, which always perform well at Domus thanks to the affinity between cinema, design and architecture, for gossip, which is popular everywhere, and for our series “a casa di” (at home with), here with the Italian writer Nicola Lagioia, the most read this year.

Finally, a bridge to the future: we decided to add three pieces of content created for social media and not for the website, namely three reels that we published on our TikTok and Instagram, projecting ourselves already into a year in which our digital presence will be even more pervasive and less and less tied to the idea of being a mere “digital conversion” of a paper magazine into digital.

Because they said the future would be in the digital world, but that future is already the present.

01

50 architecture to know: homes around the world and in history

View gallery

View gallery

“Everything is Architecture”, wrote Hans Hollein in 1968, at the height of the radical and international design movements. In the past, architecture was an art exclusively reserved for public buildings, monuments and aristocratic palaces, so the simple houses were hardly ever involved in the projects that have made the history of architecture, even though it is common knowledge that there also exists, especially for this archetype, an “architecture without architects”, as Giuseppe Pagano and Bernard Rudofsky taught us. Read more

02

15 architectural icons that no longer exist

View gallery

View gallery

Joseph Paxton, Crystal Palace, London, Great Britain (1851-1936)

Built as part of the 1851 London World's Exhibition to highlight the qualities of emerging technologies in glass and steel, the Pavilion was originally installed in Hyde Park, before being moved to another part of the town. Destroyed by fire in 1936, it inspired many other buildings that made lightness and transparency a plus in spite of the bulky architecture of the past.

Photo by Philippe Henry Delamotte on wikimedia commons

Joseph Paxton, Crystal Palace, London, Great Britain (1851-1936)

Photo on wikimediacommons

Victor Horta, La Maison du Peuple, Brussels, Belgium (1896 -1965)

The Art Nouveau complex, commissioned by the Belgian Workers’ Party, was distributed over four floors in an irregular plot and was characterised by maximum functionality and ornamental sobriety (unlike other Horta's achievements). The building was demolished in 1965 and replaced by a skyscraper, not without controversy at what was considered an architectural crime.

Photo on wikimedia commons

Ernest Flag, Singer Building, New York, USA (1899-1969)

The 187m, 47-storey building that housed the headquarters of the Singer Manufacturing Company, a famous sewing machine manufacturer, was in the years following its construction the tallest building in the world and a strongly recognised landmark in Manhattan. Community efforts to have it recognised as a historical landmark were useless: it was demolished in the late 1960s and replaced by the current One Liberty Plaza.

Photo by Jack E. Boucher on wikidata

McKim, Mead & White, Pennsylvania Station, New York, USA (1910-1963)

The Beaux Arts style building, originally a hub in early 20th century New York and a community landmark, was demolished in 1963 due to declining rail transit flows. In its place there is Madison Square Garden and the current version of Penn Station.

Photo on wikimedia commons

McKim, Mead & White, Pennsylvania Station, New York, USA (1910-1963)

Photo on wikimedia commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, Japan (1923-1967)

The complex was designed by the master of organic architecture, here still influenced by the Mayan revivalism that he was also experimenting with in the same years in Ennis House in Los Angeles. Having survived earthquakes, the timeworn building was demolished in 1963 to make way for the third version of the hotel.

Photo on wikimedia commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, Japan (1923-1967)

Photo by Roger W on CreativeCommons

Le Corbusier, Esprit Nouveau Pavilion, Paris, France 1925

The Pavilion, conceived for the 1925 International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Paris, was a full-scale prototype of a standardised dwelling composed of mass-produced elements, which aimed to promote the benefits of efficient and inexpensive technologies to meet housing demand and the need for quality housing in cities. It was widely opposed by the organisers of the event who tried to conceal it because of the disruptive, revolutionary message and explicit disavowal of Art Deco that the Expo represented. Decades after it was dismantled, a faithful copy was reconstructed in 1977 in Bologna, which now houses an exhibition venue.

Photo on wikimedia commons

Minoru Yamasaki, Pruitt-Igoe, Saint Louis, USA (1955-1974)

The large social housing project was conceived to meet the city's pressing housing need in the post-war years. In the period immediately following its construction, living conditions in the complex slowly began to decline into deep socio-economic and environmental degradation. The demolition of the 33 mammoth buildings took place between 1972 and 1974 and was accompanied by an intense debate on public social housing policies that regarded the housing complex as an obvious symbol of national failure. The demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe was one of the first demolitions of modern architectural buildings and was described by architectural theorist and historian Charles Jencks as "the day modern architecture died".

Photo United States Geological Survey – United States Geological Survey from Wikipedia

Richard Neutra, Gettysburg Cyclorama, Gettysburg, Pensylvania, USA (1958-2013)

Designed by one of the pioneers of Californian modernism, the visitor centre at the site of the Battle of Pickett's Charge during the American Civil War in 1863 housed an 1883 cyclorama by Paul Philippoteaux and an observation deck. Due to high maintenance and restoration costs, the building was demolished despite public protests and the fact that it was considered a site of outstanding historical and architectural importance.

Photo by Acroterion on wikimedia commons

Richard Neutra, Gettyburg Cyclorama, Gettysburg, Pensylvania, USA (1958-2013)

Photo by Jack Boucher on wikimedia commons

Angelo Bianchetti, Autogrill Pavesi, Montepulciano, Siena, Italy (1967-2021)

In the era of the economic boom in which Italy looked to the future with optimism and freedom sped by on four wheels, in the footsteps of the American way of life, the Pavesi bridge-type autogrill between the Bettolle-Valdichiana and Chiusi-ChiancianoTerme tollbooths was a point of reference for tourists, holidaymakers and commuters who savoured a moment of relaxation here. Autostrade per l’Italia is replacing it with two turrets, more functional, less poetic. A memory of a somewhat naive and happily dreamy past that is unlikely to return

Photo on wikimedia commons

Miguel Fisac, Laboratorios Jorba, Madrid, Spain (1970-1999)

The building on the outskirts of Madrid was an example of the balance between lightness and materiality: the articulation of the floors, staggered 45 degrees apart, suggested the image of an Asian temple (the building was commonly referred to as 'the Pagoda') while the virtuosic use of rough concrete with traces of wooden formwork winked at Brutalism. Not recognised as a historical asset to be protected, it was demolished in 1999 to make way for a new tertiary building.

Photo on wikimedia commons

Kisho Kurokawa, Nakagin Capsule Tower Building, Tokyo, Japan (1972-2022)

This mixed-use (residential and tertiary) complex is considered one of the most representative examples of the Japanese Metabolist movement, which saw the city and society as living organisms in continuous growth and transformation, to whose needs only technology could provide concrete answers. The intervention consisted of two interconnected towers containing 140 prefabricated, independent capsules, each replaceable every 25 years. Severely degraded over the years, it was demolished due to the high costs for its renovation.

Photo by Scarletgreen on CreativeCommons

Kisho Kurokawa, Nakagin Capsule Tower Building, Tokyo, Japan (1972-2022)

Photo by Ncole458 on CreativeCommons

Alison & Peter Smithson, Robin Hood Gardens, London, UK (1972-2017)

The mammoth precast concrete complex consisted of two buildings (10 and 7 storeys, totalling 213 flats). Conceived as a manifesto of progressive social housing in opposition to the rigidity of the Modern Movement, the Smithsons' project developed the theme of collective housing in close connection with that of public space (from the vast central open space to the distributive paths at height) as an essential hub of community life and sociability. Although authoritative voices were raised to prevent its dismantling due to its advanced state of decay, the work was demolished: on the occasion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London exhibited a fragment of a façade of the complex in the Pavilion of Applied Arts.

Photo by Stevecadman on wikimedia commons

Alison & Peter Smithson, Robin Hood Gardens, London, UK (1972-2017)

Photo by Stephen Richards on wikimedia commons

Bertrand Goldberg, Prentice Women's Hospital and Maternity Center, Chicago, USA (1973-2013)

The Brutalist complex was characterised by a 9-storey concrete quatrefoil tower with oval windows, cantilevered over a 5-storey rectangular body. Used as a maternity centre, with medical stations in the central core and patient wards in the four lobes, the complex curvilinear structure entered building history through the use of early computer-aided design techniques. The building was razed in 2013 when the owners, Northwestern University, needed to locate new medical research facilities in the area.

Photo by Umbugbene on wikipedia

Minoru Yamasaki, World Trade Center, New York, USA (1973-2001)

At 417m and 415m high, the twin towers were the tallest buildings in the world when they opened. The complex, built with the aim of revitalising Lower Manhattan, was inspired by the 1939 New York World's Fair exhibition, called the World Trade Center, based on an idea of global peace pursued through trade (a vision difficult to realise and drastically disregarded by history). The story of their destruction, due to the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001, is sadly well known.

Photo by pingnews.com on CreativeCommons

OMA, Netherlands Dance Theatre, The Hague, The Netherlands (1987-2015)

The complex in the centre of The Hague, in a rapidly changing area, housed not only the dance theatre designed by OMA, but also a concert hall and a hotel by other designers. The theatre was divided into three parallel programmatic zones: the stage area and the 1,001-seat auditorium; the central area with the rehearsal studios; the area of the offices, dressing rooms and dancers' common rooms. The theatre had a structure of steel beams and girders, using metal cladding with sheet rock covered with stucco, marble and gold foil. The roof had a self-supporting structure of a double layer of trapezoid folded sheet steel.

Photo by Rory Hyde on Flickr

Joseph Paxton, Crystal Palace, London, Great Britain (1851-1936)

Built as part of the 1851 London World's Exhibition to highlight the qualities of emerging technologies in glass and steel, the Pavilion was originally installed in Hyde Park, before being moved to another part of the town. Destroyed by fire in 1936, it inspired many other buildings that made lightness and transparency a plus in spite of the bulky architecture of the past.

Photo by Philippe Henry Delamotte on wikimedia commons

Joseph Paxton, Crystal Palace, London, Great Britain (1851-1936)

Photo on wikimediacommons

Victor Horta, La Maison du Peuple, Brussels, Belgium (1896 -1965)

The Art Nouveau complex, commissioned by the Belgian Workers’ Party, was distributed over four floors in an irregular plot and was characterised by maximum functionality and ornamental sobriety (unlike other Horta's achievements). The building was demolished in 1965 and replaced by a skyscraper, not without controversy at what was considered an architectural crime.

Photo on wikimedia commons

Ernest Flag, Singer Building, New York, USA (1899-1969)

The 187m, 47-storey building that housed the headquarters of the Singer Manufacturing Company, a famous sewing machine manufacturer, was in the years following its construction the tallest building in the world and a strongly recognised landmark in Manhattan. Community efforts to have it recognised as a historical landmark were useless: it was demolished in the late 1960s and replaced by the current One Liberty Plaza.

Photo by Jack E. Boucher on wikidata

McKim, Mead & White, Pennsylvania Station, New York, USA (1910-1963)

The Beaux Arts style building, originally a hub in early 20th century New York and a community landmark, was demolished in 1963 due to declining rail transit flows. In its place there is Madison Square Garden and the current version of Penn Station.

Photo on wikimedia commons

McKim, Mead & White, Pennsylvania Station, New York, USA (1910-1963)

Photo on wikimedia commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, Japan (1923-1967)

The complex was designed by the master of organic architecture, here still influenced by the Mayan revivalism that he was also experimenting with in the same years in Ennis House in Los Angeles. Having survived earthquakes, the timeworn building was demolished in 1963 to make way for the third version of the hotel.

Photo on wikimedia commons

Frank Lloyd Wright, Imperial Hotel, Tokyo, Japan (1923-1967)

Photo by Roger W on CreativeCommons

Le Corbusier, Esprit Nouveau Pavilion, Paris, France 1925

The Pavilion, conceived for the 1925 International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Paris, was a full-scale prototype of a standardised dwelling composed of mass-produced elements, which aimed to promote the benefits of efficient and inexpensive technologies to meet housing demand and the need for quality housing in cities. It was widely opposed by the organisers of the event who tried to conceal it because of the disruptive, revolutionary message and explicit disavowal of Art Deco that the Expo represented. Decades after it was dismantled, a faithful copy was reconstructed in 1977 in Bologna, which now houses an exhibition venue.

Photo on wikimedia commons

Minoru Yamasaki, Pruitt-Igoe, Saint Louis, USA (1955-1974)

The large social housing project was conceived to meet the city's pressing housing need in the post-war years. In the period immediately following its construction, living conditions in the complex slowly began to decline into deep socio-economic and environmental degradation. The demolition of the 33 mammoth buildings took place between 1972 and 1974 and was accompanied by an intense debate on public social housing policies that regarded the housing complex as an obvious symbol of national failure. The demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe was one of the first demolitions of modern architectural buildings and was described by architectural theorist and historian Charles Jencks as "the day modern architecture died".

Photo United States Geological Survey – United States Geological Survey from Wikipedia

Richard Neutra, Gettysburg Cyclorama, Gettysburg, Pensylvania, USA (1958-2013)

Designed by one of the pioneers of Californian modernism, the visitor centre at the site of the Battle of Pickett's Charge during the American Civil War in 1863 housed an 1883 cyclorama by Paul Philippoteaux and an observation deck. Due to high maintenance and restoration costs, the building was demolished despite public protests and the fact that it was considered a site of outstanding historical and architectural importance.

Photo by Acroterion on wikimedia commons

Richard Neutra, Gettyburg Cyclorama, Gettysburg, Pensylvania, USA (1958-2013)

Photo by Jack Boucher on wikimedia commons

Angelo Bianchetti, Autogrill Pavesi, Montepulciano, Siena, Italy (1967-2021)

In the era of the economic boom in which Italy looked to the future with optimism and freedom sped by on four wheels, in the footsteps of the American way of life, the Pavesi bridge-type autogrill between the Bettolle-Valdichiana and Chiusi-ChiancianoTerme tollbooths was a point of reference for tourists, holidaymakers and commuters who savoured a moment of relaxation here. Autostrade per l’Italia is replacing it with two turrets, more functional, less poetic. A memory of a somewhat naive and happily dreamy past that is unlikely to return

Photo on wikimedia commons

Miguel Fisac, Laboratorios Jorba, Madrid, Spain (1970-1999)

The building on the outskirts of Madrid was an example of the balance between lightness and materiality: the articulation of the floors, staggered 45 degrees apart, suggested the image of an Asian temple (the building was commonly referred to as 'the Pagoda') while the virtuosic use of rough concrete with traces of wooden formwork winked at Brutalism. Not recognised as a historical asset to be protected, it was demolished in 1999 to make way for a new tertiary building.

Photo on wikimedia commons

Kisho Kurokawa, Nakagin Capsule Tower Building, Tokyo, Japan (1972-2022)

This mixed-use (residential and tertiary) complex is considered one of the most representative examples of the Japanese Metabolist movement, which saw the city and society as living organisms in continuous growth and transformation, to whose needs only technology could provide concrete answers. The intervention consisted of two interconnected towers containing 140 prefabricated, independent capsules, each replaceable every 25 years. Severely degraded over the years, it was demolished due to the high costs for its renovation.

Photo by Scarletgreen on CreativeCommons

Kisho Kurokawa, Nakagin Capsule Tower Building, Tokyo, Japan (1972-2022)

Photo by Ncole458 on CreativeCommons

Alison & Peter Smithson, Robin Hood Gardens, London, UK (1972-2017)

The mammoth precast concrete complex consisted of two buildings (10 and 7 storeys, totalling 213 flats). Conceived as a manifesto of progressive social housing in opposition to the rigidity of the Modern Movement, the Smithsons' project developed the theme of collective housing in close connection with that of public space (from the vast central open space to the distributive paths at height) as an essential hub of community life and sociability. Although authoritative voices were raised to prevent its dismantling due to its advanced state of decay, the work was demolished: on the occasion of the 16th International Architecture Exhibition, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London exhibited a fragment of a façade of the complex in the Pavilion of Applied Arts.

Photo by Stevecadman on wikimedia commons

Alison & Peter Smithson, Robin Hood Gardens, London, UK (1972-2017)

Photo by Stephen Richards on wikimedia commons

Bertrand Goldberg, Prentice Women's Hospital and Maternity Center, Chicago, USA (1973-2013)

The Brutalist complex was characterised by a 9-storey concrete quatrefoil tower with oval windows, cantilevered over a 5-storey rectangular body. Used as a maternity centre, with medical stations in the central core and patient wards in the four lobes, the complex curvilinear structure entered building history through the use of early computer-aided design techniques. The building was razed in 2013 when the owners, Northwestern University, needed to locate new medical research facilities in the area.

Photo by Umbugbene on wikipedia

Minoru Yamasaki, World Trade Center, New York, USA (1973-2001)

At 417m and 415m high, the twin towers were the tallest buildings in the world when they opened. The complex, built with the aim of revitalising Lower Manhattan, was inspired by the 1939 New York World's Fair exhibition, called the World Trade Center, based on an idea of global peace pursued through trade (a vision difficult to realise and drastically disregarded by history). The story of their destruction, due to the terrorist attack of 11 September 2001, is sadly well known.

Photo by pingnews.com on CreativeCommons

OMA, Netherlands Dance Theatre, The Hague, The Netherlands (1987-2015)

The complex in the centre of The Hague, in a rapidly changing area, housed not only the dance theatre designed by OMA, but also a concert hall and a hotel by other designers. The theatre was divided into three parallel programmatic zones: the stage area and the 1,001-seat auditorium; the central area with the rehearsal studios; the area of the offices, dressing rooms and dancers' common rooms. The theatre had a structure of steel beams and girders, using metal cladding with sheet rock covered with stucco, marble and gold foil. The roof had a self-supporting structure of a double layer of trapezoid folded sheet steel.

Photo by Rory Hyde on Flickr

If sometimes wrecking balls and explosive mines are greeted with relief by those who perceive in a specific built work a disfigurement to urban decorum or human dignity (just think of the vituperated Vele in Scampia), it also happens that the destruction of an architecture takes place with deep regret beyond the Kantian aesthetic judgement of the “beautiful” or other subjectivistic evaluative parameters. Read more

03

15 works of public art that became the symbol of a city

View gallery

View gallery

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Statue of Liberty, New York, USA 1886

Donated by the French to celebrate American independence, the 93 m high Statue of Liberty has dominated the entire bay of Manhattan since 1886. Since the days when it appeared, for many migrants, as the first 'face' of the United States of America, the iconic monument has become not only the symbol of the city but also of the possibility of realising one's dreams.

Photo Liviob from Wordpress

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Statue of Liberty, New York, USA 1886

Photo cisko66 from Wordpress

Paul Landowski, Heitor da Silva Costa, Gheorghe Leonida, Albert Irenée Caquot, Christ the Redeemer, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 1931

The 38 m high soapstone statue rising from the top of Corcovado is par excellence 'the' symbol of Rio de Janeiro and the entire country: it depicts Jesus Christ with outstretched arms embracing the entire city in an ideal gesture, redeeming humanity.

Photo UNWomen gallery from Wordpress

Paul Landowski, Heitor da Silva Costa, Gheorghe Leonida, Albert Irenée Caquot, Christ the Redeemer, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 1931

Photo David Berkowitz from Wordpress

Lim Nang Seng, Merlion, Singapore, 1972

Located in the bustling Merlion Park, the 8.6m high sculpture spitting water represents the Merlion, a mythical creature with the head of a lion and the body of a fish regarded as the mascot and national symbol of Singapore. A little further away is a second 2m-high statue depicting a puppy (also of a Merlion, of course).

Photo Fad3away from Wordpress

Luis Barragán, Mathias Goeritz, Torres de Satélite, Naucalpan de Juárez, Mexico 1958

The five prismatic concrete towers of varying heights (up to 52 m) and flamboyant colours are an effective synthesis of architecture and sculpture: originally conceived as a fountain at the gates of Ciudad Satélite, on the outskirts of Mexico City, even today these 'needles' stuck in the sky are a powerful territorial landmark.

Photo Octavio Alonso Maya from Wordpress

Luis Barragán, Mathias Goeritz, Torres de Satélite, Naucalpan de Juárez, Mexico 1958

Photo Christian Gonzáles Verón from Wordpress

Robert Indiana, LOVE, Philadelphia, USA 1976

In the park dedicated to John Fitzgerald Kennedy in the heart of Philadelphia, the bright red, winking sculpture was designed to celebrate the birth of the United States of America in the site of their founding and the spirit of the 'city of brotherly love'.

Photo Trustypics from Wordpress

Eduardo Chillida, El Peine del Viento, San Sebastián, Spain 1977

At the extreme western tip of the Bahia de la Concha, there is one of Chillida's best-known compositions and strongly representative of the city: El Peine del Viento, a sculptural ensemble composed of pink granite terraces and three rusty iron elements set on the rocks, intended as one with the wind, water and waves. On very windy days, the air passes through a system of tubes emitting a magical, surreal sound.

Photo Babalooba from Wordpress

Eduardo Chillida, El Peine del Viento, San Sebastián, Spain 1977

Photo Burdellet from Wordpress

Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle, Fontaine des Automates, Paris, France 1983

Located in the Igor Stravinsky Square near the Centre Georges Pompidou, the joyful fountain consisting of a 580 m2 basin and 16 colourful aluminium sculptures that move thanks to water jets is a pleasant attraction for adults and children alike.

Photo Art_inthecity from Wordpress

Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle, Fontaine des Automates, Paris, France 1983

Photo Art_inthecity from Wordpress

Jeff Koons, Puppy, Bilbao, Spain 1997

Coherently with Koons' expressive language, the monumental West Highland terrier puppy situated in front of the Guggenheim Museum and covered with petunias, marigolds and begonias on a stainless steel structure makes kitsch an effective marketing tool. As well as of Bilbao, it is a symbol of 'love, warmth and happiness', according to the artist.

Photo Andymag from Wordpress

Alvar Gullichsen, Posanka, Turku, Finland 1999

The statue, located near the campus area of the University of Turku and the Turku Student Village, is a hybrid between a marzipan pig ('possu') and a rubber duck ('ankka'): every winter, tradition dictates that the statue is given a Santa Claus hat and, on Walpurgis Night, a student cap to playfully celebrate the return of spring and the (goliardic?) spirit of the place.

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Needle, thread and knot, Milan 2000

As part of the redevelopment of Cadorna Station and the surrounding square designed by Gae Aulenti in 1997, the sculpture is intended as a monument celebrating Milan: an allusion to the colours of the metro lines, the shapes of the city's coat of arms, and the 'sartorial' and creative tools from which the 'fashion capital' originates.

Photo Corno.fulgur75 from Wordpress

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Needle, thread and knot, Milan 2000

Photo Rémy de Valenciennes from Wordpres

Anish Kapoor, Cloud Gate, Chicago, USA 2006

Located in the middle of the AT&T Plaza in Millennium Park, the bean-shaped sculpture clad in 168 stainless steel plates, with no externally visible welds, is inspired by the fluid consistency of mercury: the reflective surface distorts the city skyline and multiplies the play of reflections, capturing the attention and curiosity of those passing under and around it.

Photo Vincent Desjardins from Wordpress

Maurizio Cattelan, L.O.V.E., Milan, Italy 2010

Photo www.ralfsteinberger.com from Wordpress

Edoardo Tresoldi, Opera, Reggio Calabria, Italy 2020

The permanent installation on the promenade of Reggio Calabria, which can be lived-in and is completely usable by citizens and visitors, is characterised by a macroscopic wire mesh structure and is a tribute to the contemplative relationship between the individual and the landscape, here evoked through a classical architectural language and material transparencies.

Anish Kapoor, Sculpture in the Monte S. Angelo metro, Naples, Italy 2022

The gigantic sculpture in the form of an inverted steel funnel located at the exit of the Monte Sant' Angelo station completes the installation conceived about twenty years ago by Kapoor and consisting of another work positioned at the main entrance. The artist's intention is to create a work of art that is not only contemplative but can be actively experienced by passing through it and living it.

Urban sculptures, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (Henry Moore, large Spindle Piece)

Thanks to the far-sighted vision of its administrators, between the 1970s and 1980s Jeddah activated a process of urban development with contemporary art at its centre: more than 600 sculptures, conceived by the world's greatest artists - including Arnaldo Pomodoro, Henry Moore, Alexander Calder,... - were placed in squares, streets and roundabouts with the aim of evoking a sense of wonder and putting the spotlight on the city as a place of cultural and artistic innovation.

Henry Moore, Large Spindle Piece, 1968

Urban sculptures, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Arnaldo Pomodoro, Rotating First Section n.3, 1975

Peeing statues, Brussels, Belgium

The three 'peeing statues' - Manneken Pis (1619), his little sister Jeanneke Pis (1985) and the little dog Het Zinneke (1998) - form an iconic monument of the city. The works, placed at the vertices of an imaginary triangle in the historic centre, refer to an expressive imagery - that of the urinating figure - that evokes the concepts of fantasy, innocence and bravado and, in this case, also the city's welcoming values and its capacity for interchange and integration.

Manneken-Pis, 1619. Photo Marco Crupi Visual Artist from Wordpress

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Statue of Liberty, New York, USA 1886

Donated by the French to celebrate American independence, the 93 m high Statue of Liberty has dominated the entire bay of Manhattan since 1886. Since the days when it appeared, for many migrants, as the first 'face' of the United States of America, the iconic monument has become not only the symbol of the city but also of the possibility of realising one's dreams.

Photo Liviob from Wordpress

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Statue of Liberty, New York, USA 1886

Photo cisko66 from Wordpress

Paul Landowski, Heitor da Silva Costa, Gheorghe Leonida, Albert Irenée Caquot, Christ the Redeemer, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 1931

The 38 m high soapstone statue rising from the top of Corcovado is par excellence 'the' symbol of Rio de Janeiro and the entire country: it depicts Jesus Christ with outstretched arms embracing the entire city in an ideal gesture, redeeming humanity.

Photo UNWomen gallery from Wordpress

Paul Landowski, Heitor da Silva Costa, Gheorghe Leonida, Albert Irenée Caquot, Christ the Redeemer, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 1931

Photo David Berkowitz from Wordpress

Lim Nang Seng, Merlion, Singapore, 1972

Located in the bustling Merlion Park, the 8.6m high sculpture spitting water represents the Merlion, a mythical creature with the head of a lion and the body of a fish regarded as the mascot and national symbol of Singapore. A little further away is a second 2m-high statue depicting a puppy (also of a Merlion, of course).

Photo Fad3away from Wordpress

Luis Barragán, Mathias Goeritz, Torres de Satélite, Naucalpan de Juárez, Mexico 1958

The five prismatic concrete towers of varying heights (up to 52 m) and flamboyant colours are an effective synthesis of architecture and sculpture: originally conceived as a fountain at the gates of Ciudad Satélite, on the outskirts of Mexico City, even today these 'needles' stuck in the sky are a powerful territorial landmark.

Photo Octavio Alonso Maya from Wordpress

Luis Barragán, Mathias Goeritz, Torres de Satélite, Naucalpan de Juárez, Mexico 1958

Photo Christian Gonzáles Verón from Wordpress

Robert Indiana, LOVE, Philadelphia, USA 1976

In the park dedicated to John Fitzgerald Kennedy in the heart of Philadelphia, the bright red, winking sculpture was designed to celebrate the birth of the United States of America in the site of their founding and the spirit of the 'city of brotherly love'.

Photo Trustypics from Wordpress

Eduardo Chillida, El Peine del Viento, San Sebastián, Spain 1977

At the extreme western tip of the Bahia de la Concha, there is one of Chillida's best-known compositions and strongly representative of the city: El Peine del Viento, a sculptural ensemble composed of pink granite terraces and three rusty iron elements set on the rocks, intended as one with the wind, water and waves. On very windy days, the air passes through a system of tubes emitting a magical, surreal sound.

Photo Babalooba from Wordpress

Eduardo Chillida, El Peine del Viento, San Sebastián, Spain 1977

Photo Burdellet from Wordpress

Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle, Fontaine des Automates, Paris, France 1983

Located in the Igor Stravinsky Square near the Centre Georges Pompidou, the joyful fountain consisting of a 580 m2 basin and 16 colourful aluminium sculptures that move thanks to water jets is a pleasant attraction for adults and children alike.

Photo Art_inthecity from Wordpress

Jean Tinguely, Niki de Saint Phalle, Fontaine des Automates, Paris, France 1983

Photo Art_inthecity from Wordpress

Jeff Koons, Puppy, Bilbao, Spain 1997

Coherently with Koons' expressive language, the monumental West Highland terrier puppy situated in front of the Guggenheim Museum and covered with petunias, marigolds and begonias on a stainless steel structure makes kitsch an effective marketing tool. As well as of Bilbao, it is a symbol of 'love, warmth and happiness', according to the artist.

Photo Andymag from Wordpress

Alvar Gullichsen, Posanka, Turku, Finland 1999

The statue, located near the campus area of the University of Turku and the Turku Student Village, is a hybrid between a marzipan pig ('possu') and a rubber duck ('ankka'): every winter, tradition dictates that the statue is given a Santa Claus hat and, on Walpurgis Night, a student cap to playfully celebrate the return of spring and the (goliardic?) spirit of the place.

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Needle, thread and knot, Milan 2000

As part of the redevelopment of Cadorna Station and the surrounding square designed by Gae Aulenti in 1997, the sculpture is intended as a monument celebrating Milan: an allusion to the colours of the metro lines, the shapes of the city's coat of arms, and the 'sartorial' and creative tools from which the 'fashion capital' originates.

Photo Corno.fulgur75 from Wordpress

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Needle, thread and knot, Milan 2000

Photo Rémy de Valenciennes from Wordpres

Anish Kapoor, Cloud Gate, Chicago, USA 2006

Located in the middle of the AT&T Plaza in Millennium Park, the bean-shaped sculpture clad in 168 stainless steel plates, with no externally visible welds, is inspired by the fluid consistency of mercury: the reflective surface distorts the city skyline and multiplies the play of reflections, capturing the attention and curiosity of those passing under and around it.

Photo Vincent Desjardins from Wordpress

Maurizio Cattelan, L.O.V.E., Milan, Italy 2010

Photo www.ralfsteinberger.com from Wordpress

Edoardo Tresoldi, Opera, Reggio Calabria, Italy 2020

The permanent installation on the promenade of Reggio Calabria, which can be lived-in and is completely usable by citizens and visitors, is characterised by a macroscopic wire mesh structure and is a tribute to the contemplative relationship between the individual and the landscape, here evoked through a classical architectural language and material transparencies.

Anish Kapoor, Sculpture in the Monte S. Angelo metro, Naples, Italy 2022

The gigantic sculpture in the form of an inverted steel funnel located at the exit of the Monte Sant' Angelo station completes the installation conceived about twenty years ago by Kapoor and consisting of another work positioned at the main entrance. The artist's intention is to create a work of art that is not only contemplative but can be actively experienced by passing through it and living it.

Urban sculptures, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (Henry Moore, large Spindle Piece)

Thanks to the far-sighted vision of its administrators, between the 1970s and 1980s Jeddah activated a process of urban development with contemporary art at its centre: more than 600 sculptures, conceived by the world's greatest artists - including Arnaldo Pomodoro, Henry Moore, Alexander Calder,... - were placed in squares, streets and roundabouts with the aim of evoking a sense of wonder and putting the spotlight on the city as a place of cultural and artistic innovation.

Henry Moore, Large Spindle Piece, 1968

Urban sculptures, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Arnaldo Pomodoro, Rotating First Section n.3, 1975

Peeing statues, Brussels, Belgium

The three 'peeing statues' - Manneken Pis (1619), his little sister Jeanneke Pis (1985) and the little dog Het Zinneke (1998) - form an iconic monument of the city. The works, placed at the vertices of an imaginary triangle in the historic centre, refer to an expressive imagery - that of the urinating figure - that evokes the concepts of fantasy, innocence and bravado and, in this case, also the city's welcoming values and its capacity for interchange and integration.

Manneken-Pis, 1619. Photo Marco Crupi Visual Artist from Wordpress

Over the centuries, public art has mainly been identified with the 'monument', understood as a hagiographic tool. But from the 20th century onwards, celebratory ambitions were abandoned in favour of more general communicative objectives linked to the context of reference. Read more

04

Brutalism in Italy, 20 architectures you should know

View gallery

View gallery

Vittoriano Viganò, Marchiondi Institute, Baggio, Milan 1957

The complex, considered a masterpiece of Brutalist architecture at an international level and today in a state of decay, is composed of four main buildings oriented along an east-west axis and immersed in a park, which house the different functional areas: offices and management, a boarding school for students, the teachers' building and a school. The plan-volume layout is characterised by a rigorous modular scansion, emphasised by the exposed concrete structure with constant pitch. Particularly innovative is the choice made by the architect, in agreement with the Institute's educators, to abolish the traditional dormitories in favour of duplex accommodation.

Photo by Alberto Trentanni from Flickr

Antonio Guacci, Marian Sanctuary of Monte Grisa, Trieste 1965

Situated at an altitude of 330 m on Monte Grisa, the sanctuary is nicknamed the 'cheese' by the people of Trieste due to its triangular shape. The complex, from which there is a spectacular view of the city, is characterised by two overlapping churches and an imposing structure in exposed reinforced concrete.

Foto di Andreas Manessinger da CreativeCommons

Enrico Castiglioni and Carlo Fontana, Cipriano Facchinetti State Institute of Higher Education, Castellanza, Varese 1965

"This building introduced into school construction - perhaps for the first time in Italy - the identification of architecture with the structure, in this case very complex in the vaulting system": this is how Castiglioni described his work, considered by Pevsner to be one of the best examples of Brutalist architecture and, according to the critics, not without references to the expressionism of Poelzig and Mendelsohn (from the dramatisation of forms to the design of the openings). The complex consists of two in-line volumes - one of which is arched in plan and façade - of three storeys above ground, arranged on a block marked by a sequence of curvilinear prefabricated reinforced concrete sheds containing the common functions. The façade is punctuated by shaped partitions and iron-window panes that curve plastically towards the top.

Photo by Roberto Conte

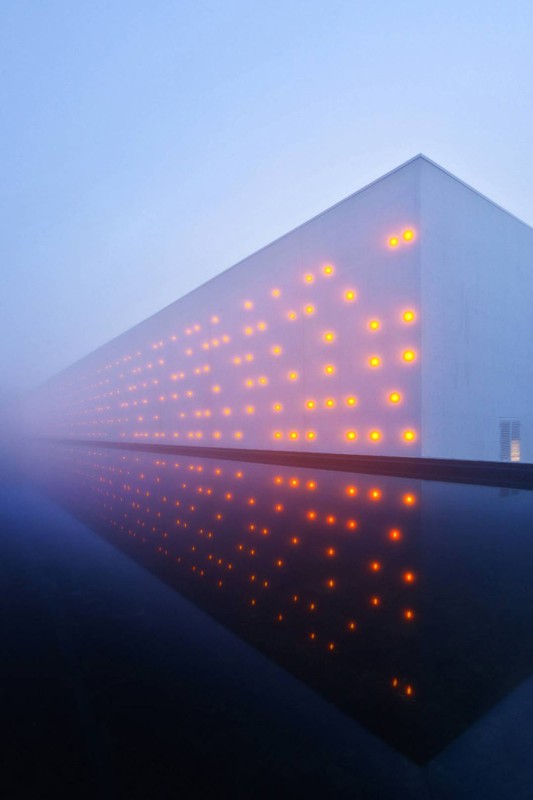

Arrigo Arrighetti, S. Giovanni Bono Church, Milan 1968

The church fits into its context by openly detaching itself from the surrounding residential buildings, thanks to its marked upward movement. The front, doubled in the image reflected by the pool in front of it, is formed by a single elongated concrete triangle pierced by coloured windows, and is reminiscent on one side of Gothic spires and on the other suggests the idea of a tent pitched in the neighbourhood. The structure consists of reinforced concrete walls with steel beams supporting a porcelain aluminium sheet roof. Next to the church there are the parish buildings and clergy residences, distributed in a semicircle around a garden.

Photo by CesareFerrari on AdobeStock

Giuseppe Perugini, Uga De Plaisant and Raynaldo Perugini, Experimental House, Fregene, Rome 1969

Reducing the so-called Casa Albero to a simple summer residence would be reductive, because the work designed by a family of architects (father, mother and son) for themselves is not just a beach house but an example of experimentation with a new architectural language in the field of housing. The work was conceived “in progress” in order to be continuously transformed, while maintaining a constant dialogue with nature. The complex consists of three buildings of different types: the house, with a repeatable modular structure made of raw concrete, glass and red steel; the ball, a 5-metre diameter sphere conceived as an external appendage to the house; the three cubes, cubic spatial modules interspersed with semi-modules containing the services, bedroom, living room and kitchen, in less than 40 square metres.

Photo by fotographicrome from AdobeStock

Francesco Berarducci, villa in via Colli della Farnesina 144, Rome 1969

The building overlooking a hill in the Monte Mario urban park is characterised by an exposed concrete structural grid composed of C-shaped pillars and beams defining the general layout and the proportional ratio of elevations. Opaque envelope portions establish a dialogue with the glazing on the main façades. The work was a backdrop for some scenes of Elio Petri's film "Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto".

Photo by CABW on wikipedia

Vinicio Vecchi, R-North Complex, Modena 1970

Located in the area north of the railway that since the war has become the site of expansion of industrial and commercial activities of the city, the multipurpose complex was created to accommodate, in addition to services and commercial activities, mini-apartments for workers of the Livestock Market. The monolithic building, characterized by a marked horizontality accentuated by the alternation of reinforced concrete floors with those of dark brick plaster, soon became a "black hole" of degradation and crime. Starting from the beginning of 2000, the complex has been the object of a regeneration intervention aimed not only to heal the physical degradation but also to face the deep-rooted social conflicts of the area: the project has provided for the dimensional revision of the lodgings to guarantee a better usability, the settlement of cultural and educational associations, the requalification of the external public spaces.

Photo by Quel palazzo che vedi dal ponte, Fotografo 1, Collettivo MaBo

Bank of Italy, Catania 1970

The building is characterised by a volume with a strong monumental impact, symbolising the institutional character of the construction The front is made entirely of concrete and is animated on the various levels in a dramatic play of light and shadow, through the tight rhythm of the exposed structure of concrete pillars and beams: expanded on the first two levels, where cyclopean pillars mark out the portico; tight on the next two floors; marked by projections and recesses on the upper levels.

Carlo Graffi, Sergio Musmeci, Villa Gontero, Cumiana, Turin 1971

The house for a Piedmontese cement entrepreneur is a passionate homage to concrete, cast in wooden formwork in beams and slabs and used in Vibramac cement blocks in the shells. The stepped progression of the volume, supported in the central part by a circular reinforced concrete structure enclosing an iron spiral staircase, creates a playful contrast between the gravity of the masses and their casual detachment from the ground. The brightly coloured windows and doorframes cast lively brushstrokes on the rough, grey elevations.

Photo by Roberto Conte

Sir Basil Spence, British Embassy Headquarters, Rome 1971

The building reconciles the designer's Anglo-Saxon brutalism with the historical context of Michelangelo's Porta Pia: the complex is characterised by reinforced concrete volumes clad with travertine panels that seek a dialogue with the colour scheme of the Aurelian walls and alternate with glass surfaces with dark bronze aluminium frames.

Photo by blackcat on wikipedia

Piero Sartogo, Headquarters of the Ordine dei Medici in Via Giovanni Battista de Rossi, Rome 1972

The building stands out with its provocative and disruptive character in the Nomentano neighbourhood, contrasting with the composed uniformity of the surrounding twentieth-century villas and buildings. The building, characterised by a sequence of overlapping and projecting volumes, evokes the image of a tree spreading its branches into the sky. On the outside, the structure reveals the internal functional division: the cubic basement with two underground levels, visible from the street, with the auditorium and library, the garage, the archives and the printing shop; the ground floor with the entrance hall and the large hall, recognisable by the full-height glazing on two floors; the first floor with the meeting room, cantilevered from the entrance; the two upper floors, housing offices, marked by a continuous metal strip that emphasises the change of function.

Domus 521, April 1973

Saverio Busiri Vici, Villa Ronconi, Rome 1973

The building is a manifesto of the purest Brutalism, recognizable in the virtuosic and plastic use of concrete, in the rough surfaces marked by the wooden formwork and in the dramatic and vibrant articulation of the structural masses, in a tight dialectic between light and dark. Now overwhelmingly transfigured in spirit, the memory of the original architecture remains and, with it, the nostalgia for a design vision that knew how to look to the essence without betraying architectural quality and refinement.

Courtesy Saverio Busiri Vici Architetto

Marco Zanuso and Pietro Crescini, Residence Porta Nuova (Gioiaotto), Milan 1973

The multifunction complex originally named Residence Porta Nuova is a representative sign of the architectural activity of the 1970s in Milan and strongly established in the city's historical memory. The reinforced concrete structure is marked by a pronounced horizontal scanning where precast concrete stringcourses delimit continuous steel and glass curtain walls. Park associati studio recently carried out a retrofitting project that interpreted the original language with philological correctness, without sacrificing meticulous attention to contemporary detail. Gioiaotto was the first LEED Platinum-certified building in Milan.

Photo by Andrea Martiradonna

Amedeo Albertini, Congress Centre Piedmont Region, Turin 1973

The Regional government congress center, formerly Federagrario e centro incontri CRT, was an imposing 8-storey building intended for offices and congress hall, composed of two symmetrical blocks with a tripartite front: a transparent basement slightly set back from the façade, a vertical development of the front designed by the contrast between the concrete stringcourses and the ribbon windows, and a glazed, set-back top. The conspicuous reinforced concrete structure with gigantic beams supported by cylindrical pillars is reminiscent of some of Kenzo Tange's renowned megastructures. In 2021 it was sold to a group of private investors and today it has been demolished to leave stage to a new building.

Giancarlo De Carlo, Matteotti District, Terni 1969 - 1975

The district, commissioned by the Terni Acciaierie company to replace the previous workers' village in order to increase the density of housing in the area, and only partially realized, is composed of four three-storey concrete buildings, with articulated stepped volumes housing 240 apartments, common terraces and roof gardens. The intervention has been the subject of a historically relevant participatory design process that involved designers, developers and residents, called to express their voice, including the need for public and private green spaces, places for social life and separation between vehicle and pedestrian flows.

Photo by Sailko from wikimedia commons

Carlo Aymonino, Aldo Rossi, Monte Armiata, Milan, 1967-1974

The "red dinosaur", so defined for the cyclopean structure, the unusual shape and the color of the facades, is a residential complex in the Gallaratese district conceived as a utopian micro-city idialoguing with Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation in Marseilles. The work includes five buildings of different heights grouped around central common spaces of aggregation (an amphitheater and two smaller squares) and numerous pedestrian paths that highlight the search for a dialectical relationship between living space and public space.

Photo by Gunnar Klack on wikipedia

Mario Forentino (design team leader), Corviale, Rome, 1975 - 1984

Corviale is the neighborhood-symbol of the degradation of the capital's suburbs. The complex, extending its cyclopic dimensions to a territorial scale (it is called "il Serpentone", “The Snake”), hosts about 4500 inhabitants and is composed of three buildings: the monumental main slab – a single 986-meter-long body on nine floors – a second lower volume, parallel to the first, and a third body rotated 45°. Franco Purini said that "Fiorentino had a conception of living as a heroic movement and that he wanted his mammoth housing machine to be a kind of community that would regulate itself by making collective interests prevail over individual ones". Unfortunately, this idealistic vision has not been supported by the facts but Corviale – despite all social problems still existing – is still a place of life and an interesting case study not only in architectural but also socio-economical terms.

Photo by Umberto Rotundo from wikipedia

Studio Celli-Tognon, residential housing complex in Rozzol Melara (Il Quadrilatero), Trieste 1982

With its cyclopean dimensions, the complex in Rozzol Melara strongly characterises the urban landscape of the city. Conceived as a semi-independent settlement system equipped with all basic services and infrastructures, rather than as a simple residential building, the project consists of two L-shaped bodies, one twice as tall as the other, grouped around a central courtyard and connected by a system of covered walkways and collective services. The building, made entirely of exposed reinforced concrete, appears compact and unified by a certain monumentality, emphasised by the rhythm of the macroscopic pillars with a 15-metre pitch that define overscaled arcades.

Photo by Dage - Looking for Europe on CreativeCommons

Michel Andrault, Pierre Parat, Madonna delle Lacrime Basilica and Sanctuary, Syracuse, Sicily 1994

The Basilica and Sanctuary of Madonna delle Lacrime (the Virgin of Tears), considered to be the largest pilgrimage church in Sicily, is the result of a design competition launched in 1957, intending to represent the importance for devotees of a miraculous event that happened four years before. The sculptural complex with a circular layout is divided into two levels – the basilica at the top and the crypt below – and is crowned by a conical concrete roof, 103 m high, surmounted by a bronze statue of the Virgin Mary.

Photo by Simone Tinella on wikipedia

Aldo D'Amore, Fabio Basile, Palace of Culture, Messina 1977-2009

The complex is characterised by a salmon-pink concrete body in the shape of a truncated, inverted pyramid with a rectangular base, housing the municipal offices, placed on top of a glazed volume that includes exhibition rooms and a theatre.

Photo by kasper2006 on wikipedia

Vittoriano Viganò, Marchiondi Institute, Baggio, Milan 1957

The complex, considered a masterpiece of Brutalist architecture at an international level and today in a state of decay, is composed of four main buildings oriented along an east-west axis and immersed in a park, which house the different functional areas: offices and management, a boarding school for students, the teachers' building and a school. The plan-volume layout is characterised by a rigorous modular scansion, emphasised by the exposed concrete structure with constant pitch. Particularly innovative is the choice made by the architect, in agreement with the Institute's educators, to abolish the traditional dormitories in favour of duplex accommodation.

Photo by Alberto Trentanni from Flickr

Antonio Guacci, Marian Sanctuary of Monte Grisa, Trieste 1965

Situated at an altitude of 330 m on Monte Grisa, the sanctuary is nicknamed the 'cheese' by the people of Trieste due to its triangular shape. The complex, from which there is a spectacular view of the city, is characterised by two overlapping churches and an imposing structure in exposed reinforced concrete.

Foto di Andreas Manessinger da CreativeCommons

Enrico Castiglioni and Carlo Fontana, Cipriano Facchinetti State Institute of Higher Education, Castellanza, Varese 1965

"This building introduced into school construction - perhaps for the first time in Italy - the identification of architecture with the structure, in this case very complex in the vaulting system": this is how Castiglioni described his work, considered by Pevsner to be one of the best examples of Brutalist architecture and, according to the critics, not without references to the expressionism of Poelzig and Mendelsohn (from the dramatisation of forms to the design of the openings). The complex consists of two in-line volumes - one of which is arched in plan and façade - of three storeys above ground, arranged on a block marked by a sequence of curvilinear prefabricated reinforced concrete sheds containing the common functions. The façade is punctuated by shaped partitions and iron-window panes that curve plastically towards the top.

Photo by Roberto Conte

Arrigo Arrighetti, S. Giovanni Bono Church, Milan 1968

The church fits into its context by openly detaching itself from the surrounding residential buildings, thanks to its marked upward movement. The front, doubled in the image reflected by the pool in front of it, is formed by a single elongated concrete triangle pierced by coloured windows, and is reminiscent on one side of Gothic spires and on the other suggests the idea of a tent pitched in the neighbourhood. The structure consists of reinforced concrete walls with steel beams supporting a porcelain aluminium sheet roof. Next to the church there are the parish buildings and clergy residences, distributed in a semicircle around a garden.

Photo by CesareFerrari on AdobeStock

Giuseppe Perugini, Uga De Plaisant and Raynaldo Perugini, Experimental House, Fregene, Rome 1969

Reducing the so-called Casa Albero to a simple summer residence would be reductive, because the work designed by a family of architects (father, mother and son) for themselves is not just a beach house but an example of experimentation with a new architectural language in the field of housing. The work was conceived “in progress” in order to be continuously transformed, while maintaining a constant dialogue with nature. The complex consists of three buildings of different types: the house, with a repeatable modular structure made of raw concrete, glass and red steel; the ball, a 5-metre diameter sphere conceived as an external appendage to the house; the three cubes, cubic spatial modules interspersed with semi-modules containing the services, bedroom, living room and kitchen, in less than 40 square metres.

Photo by fotographicrome from AdobeStock

Francesco Berarducci, villa in via Colli della Farnesina 144, Rome 1969

The building overlooking a hill in the Monte Mario urban park is characterised by an exposed concrete structural grid composed of C-shaped pillars and beams defining the general layout and the proportional ratio of elevations. Opaque envelope portions establish a dialogue with the glazing on the main façades. The work was a backdrop for some scenes of Elio Petri's film "Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto".

Photo by CABW on wikipedia

Vinicio Vecchi, R-North Complex, Modena 1970

Located in the area north of the railway that since the war has become the site of expansion of industrial and commercial activities of the city, the multipurpose complex was created to accommodate, in addition to services and commercial activities, mini-apartments for workers of the Livestock Market. The monolithic building, characterized by a marked horizontality accentuated by the alternation of reinforced concrete floors with those of dark brick plaster, soon became a "black hole" of degradation and crime. Starting from the beginning of 2000, the complex has been the object of a regeneration intervention aimed not only to heal the physical degradation but also to face the deep-rooted social conflicts of the area: the project has provided for the dimensional revision of the lodgings to guarantee a better usability, the settlement of cultural and educational associations, the requalification of the external public spaces.

Photo by Quel palazzo che vedi dal ponte, Fotografo 1, Collettivo MaBo

Bank of Italy, Catania 1970

The building is characterised by a volume with a strong monumental impact, symbolising the institutional character of the construction The front is made entirely of concrete and is animated on the various levels in a dramatic play of light and shadow, through the tight rhythm of the exposed structure of concrete pillars and beams: expanded on the first two levels, where cyclopean pillars mark out the portico; tight on the next two floors; marked by projections and recesses on the upper levels.

Carlo Graffi, Sergio Musmeci, Villa Gontero, Cumiana, Turin 1971

The house for a Piedmontese cement entrepreneur is a passionate homage to concrete, cast in wooden formwork in beams and slabs and used in Vibramac cement blocks in the shells. The stepped progression of the volume, supported in the central part by a circular reinforced concrete structure enclosing an iron spiral staircase, creates a playful contrast between the gravity of the masses and their casual detachment from the ground. The brightly coloured windows and doorframes cast lively brushstrokes on the rough, grey elevations.

Photo by Roberto Conte

Sir Basil Spence, British Embassy Headquarters, Rome 1971

The building reconciles the designer's Anglo-Saxon brutalism with the historical context of Michelangelo's Porta Pia: the complex is characterised by reinforced concrete volumes clad with travertine panels that seek a dialogue with the colour scheme of the Aurelian walls and alternate with glass surfaces with dark bronze aluminium frames.

Photo by blackcat on wikipedia

Piero Sartogo, Headquarters of the Ordine dei Medici in Via Giovanni Battista de Rossi, Rome 1972

The building stands out with its provocative and disruptive character in the Nomentano neighbourhood, contrasting with the composed uniformity of the surrounding twentieth-century villas and buildings. The building, characterised by a sequence of overlapping and projecting volumes, evokes the image of a tree spreading its branches into the sky. On the outside, the structure reveals the internal functional division: the cubic basement with two underground levels, visible from the street, with the auditorium and library, the garage, the archives and the printing shop; the ground floor with the entrance hall and the large hall, recognisable by the full-height glazing on two floors; the first floor with the meeting room, cantilevered from the entrance; the two upper floors, housing offices, marked by a continuous metal strip that emphasises the change of function.

Domus 521, April 1973

Saverio Busiri Vici, Villa Ronconi, Rome 1973

The building is a manifesto of the purest Brutalism, recognizable in the virtuosic and plastic use of concrete, in the rough surfaces marked by the wooden formwork and in the dramatic and vibrant articulation of the structural masses, in a tight dialectic between light and dark. Now overwhelmingly transfigured in spirit, the memory of the original architecture remains and, with it, the nostalgia for a design vision that knew how to look to the essence without betraying architectural quality and refinement.

Courtesy Saverio Busiri Vici Architetto

Marco Zanuso and Pietro Crescini, Residence Porta Nuova (Gioiaotto), Milan 1973

The multifunction complex originally named Residence Porta Nuova is a representative sign of the architectural activity of the 1970s in Milan and strongly established in the city's historical memory. The reinforced concrete structure is marked by a pronounced horizontal scanning where precast concrete stringcourses delimit continuous steel and glass curtain walls. Park associati studio recently carried out a retrofitting project that interpreted the original language with philological correctness, without sacrificing meticulous attention to contemporary detail. Gioiaotto was the first LEED Platinum-certified building in Milan.

Photo by Andrea Martiradonna

Amedeo Albertini, Congress Centre Piedmont Region, Turin 1973

The Regional government congress center, formerly Federagrario e centro incontri CRT, was an imposing 8-storey building intended for offices and congress hall, composed of two symmetrical blocks with a tripartite front: a transparent basement slightly set back from the façade, a vertical development of the front designed by the contrast between the concrete stringcourses and the ribbon windows, and a glazed, set-back top. The conspicuous reinforced concrete structure with gigantic beams supported by cylindrical pillars is reminiscent of some of Kenzo Tange's renowned megastructures. In 2021 it was sold to a group of private investors and today it has been demolished to leave stage to a new building.

Giancarlo De Carlo, Matteotti District, Terni 1969 - 1975

The district, commissioned by the Terni Acciaierie company to replace the previous workers' village in order to increase the density of housing in the area, and only partially realized, is composed of four three-storey concrete buildings, with articulated stepped volumes housing 240 apartments, common terraces and roof gardens. The intervention has been the subject of a historically relevant participatory design process that involved designers, developers and residents, called to express their voice, including the need for public and private green spaces, places for social life and separation between vehicle and pedestrian flows.

Photo by Sailko from wikimedia commons

Carlo Aymonino, Aldo Rossi, Monte Armiata, Milan, 1967-1974

The "red dinosaur", so defined for the cyclopean structure, the unusual shape and the color of the facades, is a residential complex in the Gallaratese district conceived as a utopian micro-city idialoguing with Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation in Marseilles. The work includes five buildings of different heights grouped around central common spaces of aggregation (an amphitheater and two smaller squares) and numerous pedestrian paths that highlight the search for a dialectical relationship between living space and public space.

Photo by Gunnar Klack on wikipedia

Mario Forentino (design team leader), Corviale, Rome, 1975 - 1984

Corviale is the neighborhood-symbol of the degradation of the capital's suburbs. The complex, extending its cyclopic dimensions to a territorial scale (it is called "il Serpentone", “The Snake”), hosts about 4500 inhabitants and is composed of three buildings: the monumental main slab – a single 986-meter-long body on nine floors – a second lower volume, parallel to the first, and a third body rotated 45°. Franco Purini said that "Fiorentino had a conception of living as a heroic movement and that he wanted his mammoth housing machine to be a kind of community that would regulate itself by making collective interests prevail over individual ones". Unfortunately, this idealistic vision has not been supported by the facts but Corviale – despite all social problems still existing – is still a place of life and an interesting case study not only in architectural but also socio-economical terms.

Photo by Umberto Rotundo from wikipedia

Studio Celli-Tognon, residential housing complex in Rozzol Melara (Il Quadrilatero), Trieste 1982

With its cyclopean dimensions, the complex in Rozzol Melara strongly characterises the urban landscape of the city. Conceived as a semi-independent settlement system equipped with all basic services and infrastructures, rather than as a simple residential building, the project consists of two L-shaped bodies, one twice as tall as the other, grouped around a central courtyard and connected by a system of covered walkways and collective services. The building, made entirely of exposed reinforced concrete, appears compact and unified by a certain monumentality, emphasised by the rhythm of the macroscopic pillars with a 15-metre pitch that define overscaled arcades.

Photo by Dage - Looking for Europe on CreativeCommons

Michel Andrault, Pierre Parat, Madonna delle Lacrime Basilica and Sanctuary, Syracuse, Sicily 1994

The Basilica and Sanctuary of Madonna delle Lacrime (the Virgin of Tears), considered to be the largest pilgrimage church in Sicily, is the result of a design competition launched in 1957, intending to represent the importance for devotees of a miraculous event that happened four years before. The sculptural complex with a circular layout is divided into two levels – the basilica at the top and the crypt below – and is crowned by a conical concrete roof, 103 m high, surmounted by a bronze statue of the Virgin Mary.

Photo by Simone Tinella on wikipedia

Aldo D'Amore, Fabio Basile, Palace of Culture, Messina 1977-2009

The complex is characterised by a salmon-pink concrete body in the shape of a truncated, inverted pyramid with a rectangular base, housing the municipal offices, placed on top of a glazed volume that includes exhibition rooms and a theatre.

Photo by kasper2006 on wikipedia

As Domus has already recounted, Brutalism developed from the 1950s onward, a time when architectural theory was reformulating the lexicon of building to cope with the needs of a society wounded by war and ready to start again. The result is an architecture that seeks to free itself from the rigidities of the Modern Movement, stripped down to the bone and unashamedly anti-hedonistic, privileging ethics over aesthetics and characterised by a straightforward functionalism, hierarchical structure and plasticity of volumes. Read more

05

Abandoned architecture in Italy: 10 buildings now disused, but not to be forgotten

View gallery

View gallery

Giuseppe Sommaruga, Grand Hotel Campo dei Fiori, Varese, Italy 1912

The feather in the cap of Varese's Belle Époque, the luxurious, late-liberty vacation complex has not withstood the changing times: from hotel, to hospital, then back to hotel again, it was closed in 1968. The gloomy and eerie atmosphere of the place, emphasised by the ravages of time, in 2016 prompted director Luca Guadagnino to set here his version of Dario Argento's famous “Suspiria”.

Photo Julius Barclay from Wikipedia

Giuseppe Sommaruga, Grand Hotel Campo dei Fiori, Varese, Italy 1912

Photo Julius Barclay from Wikipedia

Giuseppe Sommaruga, Grand Hotel Campo dei Fiori, Varese, Italy 1912

Photo Julius Barclay from Wikipedia

Luigi Cosenza, Mercato ittico, Naples, Italy 1935

The fish market in Naples is one of the major examples of the work of Luigi Cosenza, a leading figure in the Neapolitan architectural scene in the first half of the 1900s. Adhering to the principles of Rationalism, the first example in Naples, the covered market consists of a large main trading room and a series of ancillary trading spaces organized along the perimeter. The impressive barrel vault rests on iron reticular arches while the vertical heads of the building and its wide slits are closed by Saint-Gobain glass-cement, in one of the first applications in southern Italy. Although the market is restricted and subject to recovery projects, with reclamation works in progress, recent chronicles report illegal occupation acts.

Archivio Luigi Cosenza_Archivio di Stato di Napoli, Pizzofalcone

Luigi Cosenza, Mercato ittico, Naples, Italy 1935.

Archivio Luigi Cosenza_Archivio di Stato di Napoli, Pizzofalcone

Luigi Cosenza, Mercato ittico, Naples, Italy 1935.

Archivio Luigi Cosenza_Archivio di Stato di Napoli, Pizzofalcone

Renzo Zavanella, Villa dei direttori dello zuccherificio, Sermide (Mantua), Italy 1939

This work by Renzo Zavanella is a refined example of early Rationalism, expressed in the volumetric composition and the definition of the construction details. It was designed between 1931 and 1932 as a residence for the directors of an industrial complex and is characterized by some avant-garde solutions in relation to the typology of the interior spaces, such as the double-height living room and the arrangement of niches to house the built-in wardrobes, and to the technology used, like the insertion of an air gap between the two reinforced concrete walls that form the closures. Studies are still underway for the recovery of this precious architectural testimony.

Photo by Davide Galli Atelier

Renzo Zavanella, Villa dei direttori dello zuccherificio, Sermide (Mantua), Italy 1939

Photo by Davide Galli Atelier

Renzo Zavanella, Villa dei direttori dello zuccherificio, Sermide (Mantua), Italy 1939

Photo by Davide Galli Atelier

Renzo Zavanella, Villa dei direttori dello zuccherificio, Sermide (Mantua), Italy 1939

Photo by Davide Galli Atelier

Mario Loreti, Colonia Varese, Cervia (Ravenna), Italy 1939

Inaugurated with the name of the hierarch Costanzo Ciano, this colony could accommodate up to 800 children. The complex is part of a green area of approximately 60,000 square meters with a planimetric scheme based on rigid symmetry. The central body was used for distribution, while the side pavilions were for dormitories and service spaces. During the war, the building was occupied by the Germans and later fell underused until it was definitively abandoned. Between the 70s and 80s Marcello Aliprandi and Pupi Avati used the Varese colony as a set for the films La ragazza di latta and Zeder.

Foto by Roberto Conte

Alberto Galardi, Istituto Marxer, Loranzè (Torino), Italy 1962

The Marxer Institute is a rare example of brutalist architecture in Italy, commissioned by Adriano Olivetti to house production and research in the pharmacological field for the homonymous company. The complex is divided into two main volumes, which housed offices, research laboratories, and the production plant, and an existing building with the canteen and other functions. From the end of the seventies, the socio-economic transformations led to several changes of ownership and progressive underuse along with degradation processes fueled by the action of time and by acts of vandalism.

Photo by Roberto Conte

Alberto Galardi, Istituto Marxer, Loranzè (Torino), Italy 1962

Domus 394, September 1962

Giuseppe Davanzo, Foro Boario, Padova, Italy 1968

The Foro Boario was created to host livestock trading, exchange, and exhibition. The structural conception based on the iteration of a horizontal and vertical geometric module generates a large, bright, and airy covered space, whose architectural quality has earned various acknowledgments such as the In/Arch Award in 1969, the interest of the MoMA of New York, and a relatively premature monumental constraint as an element of active qualification and an episode of extremely high emergence in the surrounding urban environment, defined in a totally new way. Once the city's project to establish an international forum collapsed, this cathedral, as it was called by many, fell into disuse and is today at the center of interest of the Lille multinational Leroy Merlin.

Photo by Roberto Conte

Giovanni Giannattasio Ufo Bar, Salerno, Italy, 1970s

The Ufo Bar was a small, today abandoned, nightclub on the coastal road out of Salerno, shortly after the Arechi stadium and near a service station. The building designed by Giovanni Giannattasio has the shape of a spherical cap pierced by small portholes. Two oblique walls mark the entrance and, once crossed the threshold, it seems to enter some Tatooine tavern from Star Wars. Theater of the Salerno nightlife until the end of the 1990s, the Ufo Bar has ceased activity since the authorities affixed the seals after some illegal activities were found upon inspections.

Photo by Roberto Conte

Dante Bini, La Cupola, Sassari, Italy 1970

The dream of a house by the sea on the shores of a wild coast and the meeting with a visionary architect led to the conception and construction of a futuristic building: a sphere in reinforced concrete inextricably integrated into the surrounding marine landscape. The Binishell patent convinces a couple, director Michelangelo Antonioni and the actress Monica Vitti, to rely on Dante Bini to realize their home in Sardinia. The house is built in a single casting of concrete using air pressure. The conclusion of the relationship between Antonioni and Vitti created the conditions for gradually abandoning the structure and the inevitable deterioration.

Domus 1026, July2018

Aldo Rossi e Gianni Braghieri, Stazione di Milano San Cristoforo, Milano, Italy 1983.

The expansion of the San Cristoforo station was commissioned to build a terminal for the transport of private cars along the Milan-Paris line. The construction was never completed due to the client's constant rethinking until the definitive abandonment of the works in 1991. Today we can virtually read the masses of the ruined skeleton and imagine the transit of vehicles in the area in front. The debate on the future of this unfinished building is destined to continue in the years to come in light of the transformation program affecting the Milanese railyards.

Photo by Gerardo Semprebon

Aldo Rossi e Gianni Braghieri, Stazione di Milano San Cristoforo, Milano, Italy 1983.

Photo by Gerardo Semprebon

Aldo Rossi e Gianni Braghieri, Stazione di Milano San Cristoforo, Milano, Italy 1983.

Photo by Gerardo Semprebon

Aldo Rossi e Gianni Braghieri, Stazione di Milano San Cristoforo, Milano, Italy 1983.

Photo by Gerardo Semprebon

Consonno (Lecco), Italy 1960s

It was the early 1960s when the entrepreneur Mario Bagno bought the land in the district of Consonno and razed the few houses abandoned after the crisis in the agricultural sector to build a new Toyland. Focused on the tourism industry, Consonno housed shops, restaurants, sports fields, a dance hall, a luxury hotel, an amusement park, a zoological garden, a medieval castle as an entrance gate, and the notorious minaret. In 1966, the first of two landslides that would have marked the future of this place within ten years, isolated the town, showcasing the consequences of excessive overbuilding and land taking. It was the beginning of a gradual abandonment that turned the themed village into a ghost town.

Photo on Wikicommons

Vico Magistretti, Housing complex at Marina Grande, Arenzano (Genova), Italy 1065

The complex was built as a real estate initiative commissioned by Cemadis S.p.A. acronym of Centro Marittimi di Soggiorno, against the backdrop of the urbanization plan of the Arenzano pine forest. The 300 meters of shops, streets, public spaces, services, car parks, and residences are organized on basements connecting the different coast levels and above-ground blocks organized around courtyards and patios shaped to maintain controlled scalar relationships. Over the years, the residents have gradually abandoned the structure, leaving the public spaces for the use of bathers and passers-by. The presence of several owners with heterogeneous interests has contributed to slowing down the initiatives for functional recovery.

Giuseppe Sommaruga, Grand Hotel Campo dei Fiori, Varese, Italy 1912

The feather in the cap of Varese's Belle Époque, the luxurious, late-liberty vacation complex has not withstood the changing times: from hotel, to hospital, then back to hotel again, it was closed in 1968. The gloomy and eerie atmosphere of the place, emphasised by the ravages of time, in 2016 prompted director Luca Guadagnino to set here his version of Dario Argento's famous “Suspiria”.

Photo Julius Barclay from Wikipedia

Giuseppe Sommaruga, Grand Hotel Campo dei Fiori, Varese, Italy 1912

Photo Julius Barclay from Wikipedia

Giuseppe Sommaruga, Grand Hotel Campo dei Fiori, Varese, Italy 1912

Photo Julius Barclay from Wikipedia

Luigi Cosenza, Mercato ittico, Naples, Italy 1935