by Alessandro Scarano

In a small amphitheater overlooking the June sun-drenched street that separates Barcelona’s historic Fira Montjuic from the nearby Pavelló Italià, a group of people gathers. They bear witness to the presentation of new AI-powered musical instruments (Waive Studio) and virtually created artists with the launch of a new tech-sharing platform supported by the Dutch government, Open Culture Tech. Meanwhile, on the lower level, the spacious project area hosts London-based 3D artist Dan Hoopert, who presents his generative experimental projects related to images and sounds.

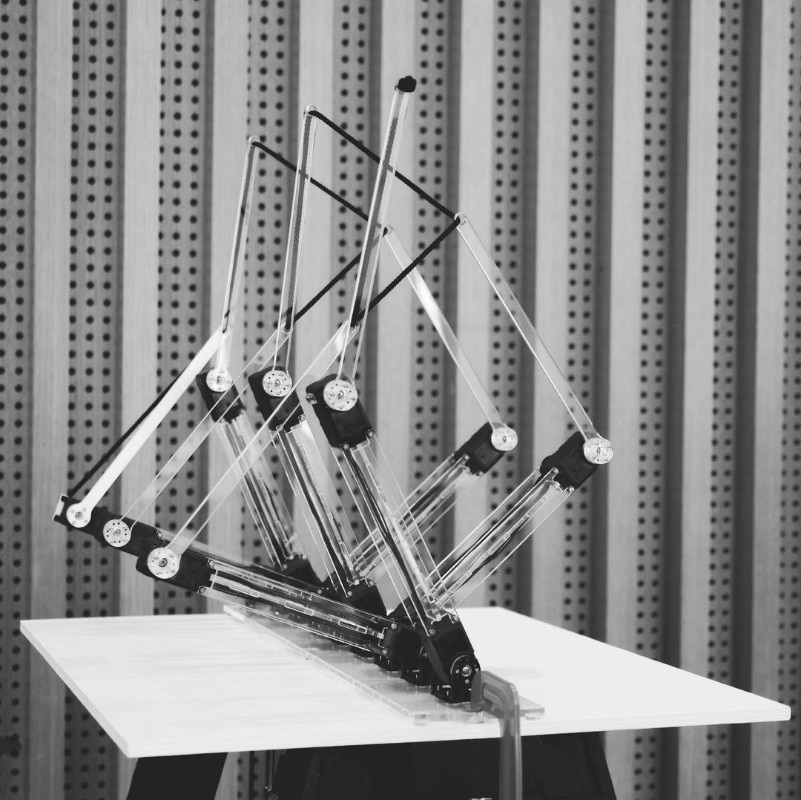

On the opposite side of the room is Weirdcore and Aphex Twin’s “black box”, beckoning viewers into a universe of augmented reality wonders with a simple frame of their cell phones. The space is abuzz with presentations of projects, ranging from student works, including the captivating Other Matter, to explorations of machine typography by Japanese designer Yuichiro Katsumoto at the Barcelona Supercomputing Center. Among the highlights is Enakd, an interface that translates brain waves through a helmet to create visuals and poems. There is also a dedicated section that showcases synthesizers, while in a side room twelve VR projects from the Realities program await exploration through a visor. On the upper floors, talks, panels, and even shows intertwine with the daytime program of Sónar, the renowned international festival of “Music, Creativity & Technology”, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary.

This section, known as +D, has been in existence for approximately a decade, ever since Sónar, renowned as Europe’s most popular electronic and experimental music festival, relocated its daytime activities to the historic Fira Montjuic. To comprehend its evolution, we need to take a step back, Antonia Folguera, the curator of the last seven editions of +D tells Domus.

Sónar was originally established in 1994 at the CCCB cultural center, situated in the vibrant melting pot of Barcelona’s Raval neighborhood, alongside the notable cultural and museum institution, MACBA. From its inception, Sónar not only catered to the public but also engaged professionals in the industry. This segment, initially named Sónar Pro, steadily grew and expanded to include artistic installations and film programming, eventually focusing on virtual reality. Folguera explains, “It was an opportunity to explore what was then known as ‘electronic culture’ – a niche and avant-garde movement”.

Sónar +D now encompasses the shared realm of science, technology, art, and music. Throughout the years, it has explored recurring themes, such as this year’s prominent focus on artificial intelligence. “Given the rise of Midjourney and chatGPT, it was a natural choice”, comments the curator. However, machine learning and deep learning have been subjects of extensive discussion in previous years as well.

In her conversation with Domus, Folguera opens three Pandora’s boxes. Firstly, she unveils the hidden facets of Barcelona, going beyond the iconic postcards of Gaudi and the bustling Rambla, the June 2 weekends at Primavera Sound, and the retirees constantly streaming from Easyjets to the Sagrada Familia. Barcelona is a city of innovation, nurturing startups, hosting the world’s most relevant mobile trade show (the MWC), and housing the cutting-edge Centro Nacional de Supercomputación. Secondly, she delves into the significance of cultural programming within a music festival. She emphasizes that a music festival without meaningful cultural elements and that doesn’t engage audiences with art, creativity, and music feels lifeless and becomes an end unto itself. Lastly, Folguera highlights the ease of discussing this year’s most relevant theme at Sónar, compared to the pompous and fragmented Design Week in Milan. In Milan, the occasional experiments in AI creativity were overshadowed by the overwhelming grandeur of the mega-event, where countless tables and chairs obscured the view, hindering the focus on present, future, and urgent matters.

The beauty of mistakes

View gallery

View gallery

In a year dominated by discussions surrounding Artificial Intelligence and its increasing integration into our daily lives, Sónar presents numerous projects that not only utilize AI but also analyze and, at times, criticize it. Pau Garcia, CEO of Domestic Data Streamers – an “info-experience” studio known for their decade-long work in creating digital storytelling projects with refugees, women affected by violence, and exploring memories of the Spanish dictatorship – emphasizes the importance of demystifying AI. While recognizing AI as a valuable tool, Garcia urges caution regarding its potential outcomes. He highlights the risk of AI systems creating standardized norms that can marginalize those who do not conform to these standards.

The significance of complexity in approaching artificial intelligence is reiterated by Joel Gethin Lewis, who is present at Sónar to showcase six distinct projects from Universal Everything. As the interactive creative director of this digital design collective with an impressive track record of collaborations spanning from ZHA to Radiohead, Hyundai to Apple, Gethin Lewis prefers to use terms like “machine learning” or “generative systems” rather than AI. In conversation with Domus, he emphasized the need to avoid falling into binary thinking when reasoning, as computers themselves do not operate in such a manner, he explained.

Sónar’s 30th-anniversary celebration also incorporates the use of AI. Sergio Caballero, co-founder, and co-director of Sónar, has created a project placed within a black cube that condenses thirty years of Sónar’s imagery into a mesmerizing 39-minute looped immersive video installation. Using Artificial Intelligence, Caballero merges Sónar’s past advertising campaigns, which have often been controversial yet impactful, into new sequences, resulting in hybrid and sometimes monstrous figures. These fluid dreams on the screen blend humans and machines, animals and furniture, accompanied by music composed by Fennesz. Large posters featuring these images can be seen throughout the city. “It is in the beauty of these errors that Sónar found the image for its 30th-anniversary edition”, reads the project’s presentation.

Beyond bodies, inside holograms

“You have to find the wrong way to use things, just like scratch artists do with turntables”, Daito Manabe tells Domus. The Japanese artist embodies the essence of Sónar +D as a musician, performer, visual artist, programmer, co-founder of Rhizomatiks, and lecturer at Keio University SFC. At +D, amidst stages where talks and performances coexist, lively dances bring together individuals of various ages and styles, from sixty-year-olds in Euphoria-style makeup to barefoot children dancing in the recesses of the VIP area, and neo-goths twerking alongside new-age kids experiencing their first post-Covid festival, Manabe takes on the dual role of lecturer and performer, delivering a talk on Thursday and a show the following afternoon.

Many stop him for a selfie. When we met on Friday, he had just injured his finger with a knife – an almost paradoxical incident, he explains, for someone who is currently exploring the boundaries of the human body through research. He is working on a sort of brain avatar. As we speak, Manabe’s gaze remains fixed on a point in space that I cannot discern, as if he was looking into the future, not in a metaphorical sense. It is from this precise corpuscle, visible only to him, that he draws remarkable visions, vividly conveyed through his words. In the broken rhythm dictated by the translation, his words are encapsulated in long fragments that speak of future projects and splinters of the past. He reflects on his days as a math student, when he realized that music and video are nothing more than files with different outputs – entities of the same essence. He reminisces about his early experiments with Google’s Deep Dream machine learning in 2015, the music and video performance he presented at Sónar the previous night, and his exploration of the next stage of AI known as Life Intelligence. He also shares his ongoing experiments with electrical pulses on rat brain cells, conducted at the University of Tokyo in the realm of computation. “The body bores me”, he explains, symbolically displaying a band-aid on his injured finger.

View gallery

View gallery

On the contrary, the 120,000 or so attendees at this year’s Sónar are far from bored. Especially when a colossal robotic hand reaches out to them, inviting them to take a selfie, or when floating whales, constellations, and spacesuits reminiscent of Nintendo’s unreleased Metroid series fill the air. These images are part of Holo, the three-dimensional space opera presented by Swedish DJ Eric Prydz, who is making his appearance at Sónar following his debut at Coachella in April. The setting in the vast, crowded halls of the Fira Europa Gran Via during nighttime Sónar creates a truly unique atmosphere. A mass of semi-naked individuals sway to the beats of Prydz’s bpm’s, only to pause abruptly, pull out their phones, and capture the three-dimensional sequences of the show in digital memory. And then they dance again.

For decades, we have eagerly anticipated the emergence of holograms. Even before Apple’s Vision Pro made its debut, luminaries like Burroughs and Bowie discussed holograms in a now-famous interview from the 1970s, in which they practically gave them away as a done deal. Today, we can interpret their significance in a different light: as a testament to the remarkable growth of visual elements in concerts, particularly within the realm of electronic music. Holograms have replaced the coordinated imagery that once made music iconography so influential in the twentieth century, when it resided on physical media, and opening an LP meant immersing oneself in a new world. “But don’t tell the musicians”, chuckles Weirdcore, wearing his trademark cap and Aphex Twin’s new tour T-shirt. Aphex Twin, an electronic music deity whose futuristic sound has captivated audiences for three decades, is a prominent headliner at this year’s Sónar festival. “I curate both the visuals and merchandise”, Weirdcore explains. Together with Black Box Echo who handles the visual components of British duo Bicep’s concerts, he tells in SónarÀgora about the unique and relatively new role of the artist who creates real-time concert visuals on massive screens, using special software that allows for improvisation with materials stored in data centers the size of a pocketbook. These artists are akin to what Duffy was to Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust or Anton Corbijn was to Depeche Mode and U2. “U2 who?” jokes Weirdcore.

Visuals, an increasingly important form of art

The art of visuals has been present for many years, yet it always sounds like something new. “I never know what Richard (Richard D. James, Aphex Twin, Ed.) is going to play”, reveals Weirdcore to Domus. “Perhaps he doesn’t even know himself”, he adds with a smirk. His visuals follow the music, using preset images that are mixed and modulated on the spot. “When I started working with him, I spent a lot of time figuring out what he liked”. It turns out they both like very similar things. During live performances, Weirdcore makes heavy use of the iconic Aphex Twin logo, a powerful symbol created in 1991 by Paul Nicholson that has now permeated mass culture, with several Instagram accounts paying homage to it.

This year marks the 14th year of collaboration with James. But routine doesn’t really exist in their work. “Something has changed on the new tour”, as the musician has flipped the approach to live shows. Rather than progressive crescendos, the performances now consist of alternating waves, incorporating moments of pause and devastating crescendos. “I have to adapt quickly to keep up with them”, explains Weirdcore, describing how he had to redesign sequences to align with the new rhythm. The real face of Richard David James remains hidden behind a grid throughout the live show, while Weirdcore strives to provide him with a shared visual identity. Because not only do we want to hear the music, we also want to see it more and more.

Opening image: Eric Prydz, Holo. Photo by Martini Ariel

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)

.png.foto.rmedium.png)