About ‘Design Criminals’

A text by Sam Jacob:

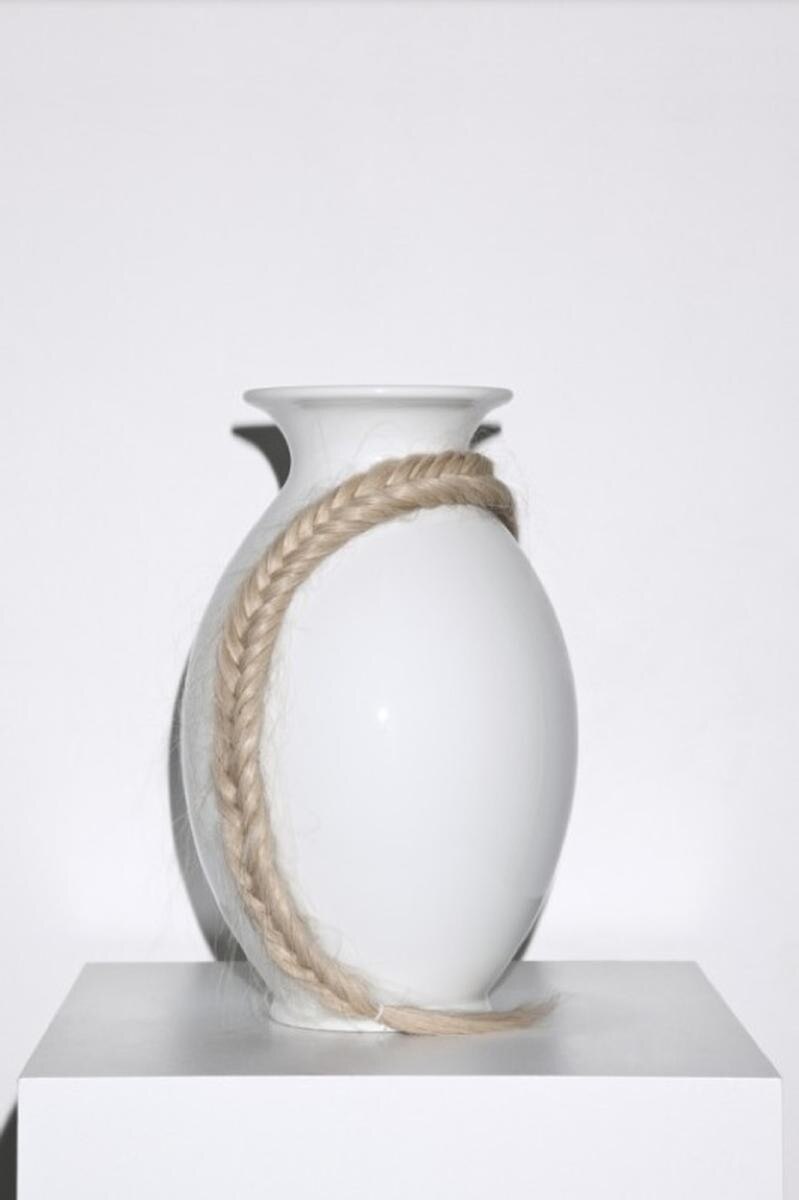

There are certain things that are beyond the normal canon of design activity. These are things that you won’t see in design magazines or museums. Things that are so ingrained in everyday experience that they don’t necessarily register as design acts. But they are things that nevertheless display their own aesthetic, material and formal frameworks in ways that make them fully fledged design subcultures. These vernacular forms of design might include such things as cake decoration, tattoos, hairdressing and flower arranging – the kinds of things that we might make ourselves or have made for us, the kinds of things ingrained in everyday activities and rituals. They might not stand in any grand traditions but that doesn’t stop them being important sites of cultural expression. These are a kind of design that operate at the intersection of the intimate with the public, in the space between us and the world around us. They are devices that can be expressions of sentiments like love, ways of constructing identity or means of projecting our desires into the world. Despite their often-slight form, they can carry with them intense forms of social meaning articulating a sense of ourselves and signifying our presence in the world. These forms of design activity seem to operate under different terms to those of ‘high’ design. We might ask what it is that makes these approaches distinct from one another? Why the approaches of product, furniture, graphics and architecture differ from these everyday forms of design? And we might also ask: What might high design be able to learn from these other sources? These everyday forms of design are often decorative and ornamental – ideas which have troubled high design since Adolf Loos’s extraordinary essay Ornament and Crime. Loos characterised the use of ornament in the age of industrial production as wasteful and morally wrong. It was, Loos argued, a way of disguising the essence of an object. By removing ornament, design could instead reveal its truths. But truth is always slippery – and even more so when addressed though the language of things. The project of Design Criminals is to question and explore the ways in which vernacular design cultures might themselves be able to address various kinds of truth. Because they position design as an activity that operates socially as well as within its own material and craft techniques, we might argue that they address a different register of truth to that which Loos (and, subsequently high design traditions of the twentieth century) sought. Indeed, we might also argue that drawing on the ‘degenerate’ and ‘criminal’ aspects of a wider culture of objects is a way of re-stating Loosian demands upon design. Design Criminals asks questions about designs role as a social act. The collaborations engage high design with different sets of techniques and materials, with unfamiliar sites and with scenarios that challenge their normal autonomous relationship to the everyday. By occupying a position between traditional definitions of high and low, between the special and the ordinary, it seeks to ask questions about the intimate moralities, revolutions and truths that surround us. In another Loosian phrase, Design Criminals explores the potential of the decorative and ornamental to deliver ‘new joy into the world’

Vanità Living: The Mirror Revolution at Salone del Mobile

Vanità Living unveils "Ercole" and "Flirt" at Salone del Mobile 2025, innovative mirrors for personalized lighting based on “Ghost Mirror” technology. The Aviano company, focused on sustainability and safety, reaffirms its leadership in the design furniture sector.