An international artistic adventure, between revolution and reaction, cosmopolitism and province, constant and ephemeral, ‘sublime’ and whimsical

The Art Nouveau is described through these words by art and architecture critic and historian Lara-Vinca Masini, in her seminal monographic publication from the 1970s.

Revolution: the Art Nouveau season unfolds from the last decade of the 19th century to the early 1910s, in the wake of the European Industrial Revolution, which radically renewed the modes, times and goals of production, even in the artistic field. Reaction: Art Nouveau’s supporters shows a more problematic attitude than an unequivocal, positivist-based faith in the potentials of progress. Rather, against the potentially infinite replication of the industrial object, flattened through its multiplication, they rediscover and bring up to date the know-hows of traditional craftsmanship.

Cosmopolitism: the Art Nouveau crosses the entire European continent, to further spread in North America. International Exhibitions, for instance in Paris in 1900 and in Turin in 1902, are pivotal occasions for the debate and the circulation of models and sensitivities. The movement has different declinations in each national context, as well as a specific denomination: Art Nouveau is mostly used in Belgium and in France, where other options such as Style Guimard and Style 1900 are also common; Jugendstil and Sezessionstil are inherent in the German and in the Austrian contexts respectively; Spain opts for Modernism, and Italy for either Stile Liberty or Stile Floreale. Province: the Art Nouveau is hugely popular also outside of the traditional hotspots of art production, provinces where it often participates in the celebration and the modernization of local identities.

Constant and ephemeral: the Art Nouveau claims that art and life are inseparable, the former affecting each and every aspect of the latter (l’art pour l’art, according to the famous expression popularized by poet Théophile Gautier). All artistic disciplines are concerned, from the most permanent, such as architecture, painting and sculpture, to the most ephemeral, such as furniture design, exhibition design and set design. It is not by chance that the Art Nouveau movement is considered as the forerunner of contemporary industrial design. Within the frame of this synesthetic experience, Giovanna Massobrio and Paolo Portoghesi stress the restored relevance of architecture: “the hierarchy of arts doesn’t proceed from the least conditioned to the most preoccupied with economic and social factors, according to Hegel’s thesis, widely shared by European scholars and artists; rather, it spans from architecture, which is the most comprehensive and synthetic, to the other arts, which provide their different techniques, useful to define space and to make it suitable to various human activities”.

View gallery

View gallery

Giuseppe Sommaruga, Campo dei Fiori Grand Hotel, Varese, 1908-1912. From Domus 506, January 1972

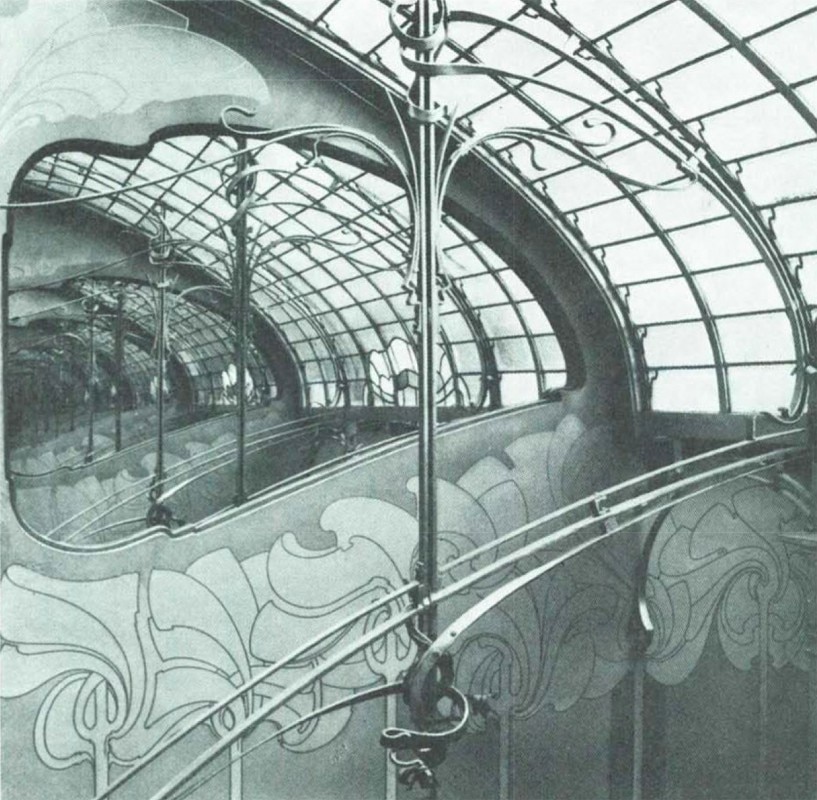

Raimondo D’Aronco, concert marquee, Udine, 1903 (reconstruction). Photo © Elio Ciol. From Domus 633, November 1982

Raimondo D’Aronco, concert marquee, Udine, 1903 (reconstruction). Photo © Elio Ciol. From Domus 633, November 1982

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, 1905-1908. Photo © Rafael Vargas. From Domus 940, October 2010

Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, 1905-1908. From Domus 940, October 2010

Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, 1905-1908. Photo © Oscar Tusquets Blanca. From Domus 940, October 2010

Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, 1905-1908. From Domus 940, October 2010

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Rafael Vargas. From Domus 945, March 2011

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Rafael Vargas. From Domus 945, March 2011

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Rafael Vargas. From Domus 945, March 2011

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow, 1896-1909. Extension by Jean Nouvel, 2014. Photo © Edmund Sumner. From Domus 980, May 2014

Giuseppe Sommaruga, Campo dei Fiori Grand Hotel, Varese, 1908-1912. From Domus 506, January 1972

Raimondo D’Aronco, concert marquee, Udine, 1903 (reconstruction). Photo © Elio Ciol. From Domus 633, November 1982

Raimondo D’Aronco, concert marquee, Udine, 1903 (reconstruction). Photo © Elio Ciol. From Domus 633, November 1982

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Phil Sayer. From Domus 848, May 2002

Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, 1905-1908. Photo © Rafael Vargas. From Domus 940, October 2010

Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, 1905-1908. From Domus 940, October 2010

Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, 1905-1908. Photo © Oscar Tusquets Blanca. From Domus 940, October 2010

Lluís Domènech i Montaner, Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona, 1905-1908. From Domus 940, October 2010

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Rafael Vargas. From Domus 945, March 2011

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Rafael Vargas. From Domus 945, March 2011

Antoni Gaudí, Sagrada Familia, Barcelona, 1882-ongoing. Photo © Rafael Vargas. From Domus 945, March 2011

Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Glasgow School of Art, Glasgow, 1896-1909. Extension by Jean Nouvel, 2014. Photo © Edmund Sumner. From Domus 980, May 2014

Therefore, all through the short-lived and troubled Belle Époque decades, the Art Nouveau builds the landscapes of the new bourgeoisie, which has gotten wealthier and more politically and culturally relevant thanks to the Industrial Revolution. Domestic interiors and urban spaces, with their facilities and infrastructures, adapt to the dominant “taste” (a substantially bourgeois notion). Nature, whose throughout knowledge is ensured by that age’s major scientific advancements, is a constant source of inspiration for a movement which strives for a complete unity between structure and decoration. Sinuous lines and organic volumes draw more or less faithful inspiration from the natural world, both vegetal and animal.

These are the common preconditions that produce a strong thread link connecting the works of Art Nouveau architecture’s leading figures. All of them are variously indebted to the ground breaking experience of the English Arts & Crafts movement, led by William Morris (1834-1896). Amongst them is Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928), from Scotland, who designs the Glasgow School of Art (1896-1909); Hector Guimard (1867-1942), from France, best remembered for the entrances to Paris metro stations (1867-1942), as well as for the Castel Béranger (1898), also in French capital; Henry van de Velde (1863-1957), from Belgium, and his compatriot Victor Horta (1861-1947), the author of a few early Art Nouveau works such as the Maison Tassel (1893), as well as of the impressive and yet destroyed Maison du Peuple (1896-1899), both in Brussels; August Endell (1871-1925), from Germany, who builds the Elvira photo atelier (1896-1897) in Munich. Besides: the promoters of the Catalan Modernism such as Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926), the architect of the Casa Batlò in Barcellona (1904-1906), and of the Sagrada Familia, started in the same city in 1882 and still waiting for its completion; the interpreters of Wien Sezessionstil, including Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867-1908) and Otto Wagner (1841-1918), the author of the Postsparkasse (1904-1906) and of many Wien Stadtbahn’s stations (1895-1900); the protagonists of the Italian Style Liberty such as Pietro Fenoglio (1865-1927, from Turin), Giuseppe Sommaruga (1967-1917, from Milan), Gino Coppedè (1866-1927, from Florence) and Ernesto Basile (1857-1932, from Palermo). American architects from the same generation are also involved, including Louis Henry Sullivan (1856-1924), who designs the Carson Pirie and Scott Company Building in Chicago (1899-1904).

Starting from the early 1910s, the rise of the avant-gardes and later of the Modern Movement, in addition to the different political, economic and social context following the First World War, lead to the ultimate extinction of the Art Nouveau movement. A few decades of significant critical misfortune and forgetfulness follow, when it is simplistically interpreted as a decorative style, and inaccurately generalized as a variation of 19th century eclecticism. Many valuable architectures are either demolished or irreparably altered. Architecture historian Nikolaus Pevsner is the first to contribute to its rehabilitation, through the more acute historiographic interpretation that he gives in his 1936 book Pioneers of Modern Design. From the 1950s, a more widespread reconsidering of the Art Nouveau eventually establishes itself, leading to its full reintegration amongst the movements which made the history of Western architecture in the 20th century.