By the mid-1990s, Jean Nouvel had become a reference figure on the international architectural scene, having associated his name with buildings of major urban importance such as the Opéra in Lyon. The first of this series, which marked the public debut of the architect who would later also become Domus guest editor, was the Institut du Monde Arabe, one of the landmark works in the Grands Projets, the spatial transformation program of 1980s Paris during the Mitterrand presidency. In the following decade, Nouvel returned to the capital for another project that was primarily concerned with urban space: the glass-and-steel volume of the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain, which Domus published in issue 766 of December 1994. This building, too, was destined to become an icon of an era, and is now ready to salute the opening of its successor in the historic centre of Paris, the new headquarters of the Fondation on the rue de Rivoli, near the Louvre.

The new building of Fondation Cartier in Paris

Seven years after completing the Institut du Monde Arabe, the work that rocketed him into the international limelight, the Parisian architect has returned to build in his home city. A large-scale building, it measures up to the traditional urban fabric by using the light tools of absolute modernity.

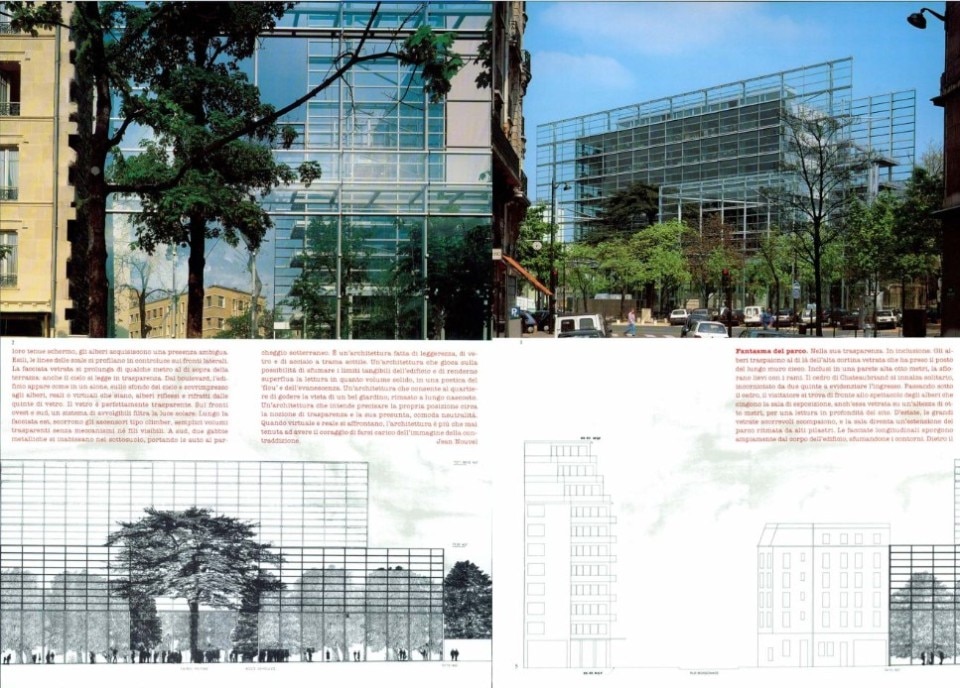

A phantom of the park. In its transparency. In a see-through setting. Appearing behind the high glass curtain wall which now replaces the long blind fence, the trees seem captured in the eight meter panes — their foliage gently brushing against them. The cedar of Chateaubriand rises, solitary, framed between the two screens defining the entrance. The visitor passes beneath the cedar and receives the spectacle of the trees surrounding the glass exhibition hall, also eight meters high, thus fully experiencing the depth of the site.

In summer, the large sliding bays disappear and the hall, now a rhythmical set of tall columns, becomes an extension of the park. The longitudinal facades reach beyond the main structure, while blurring its boundaries. The trees, as if gliding behind them, acquire an ambiguous presence. The thin staircases are silhouetted in the light against the side walls. The glass panes extend beyond the terrace by a few meters. The sky itself is read through this transparency. Seen from the boulevard, the building appears bathed in a halo of light, superimposed against a backdrop of sky and trees, both real or virtual, reflected and refracted by the screens of glass. The glass is clear. The west and south walls filter the light with their rolling blinds. Along the east facade, glide ‘climber’ type elevators, simple transparent volumes, without any apparent controls or cables. To the south, two metal grilles sink into the ground leading cars to the underground parking garage.

It is an architecture all about lightness, glass, and fine steel gridwork. An architecture whose rules consist in blurring the tangible limits of the building and rendering superfluous the reading of solid volumes in a poetry ofhaze and evanescence. An architecture which offers the neighbourhood the pleasure of a beautiful garden which for a long time had been concealed from sight. An architecture which makes clear its position on the notion of transparency and its alleged idle neutrality. When the virtual confronts the real, the architecture must, more than ever, have the courage to assume the image of contradiction.