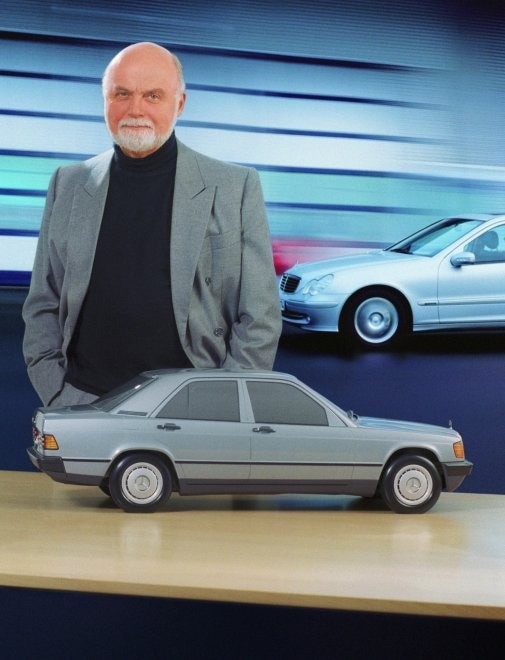

A luminous striated band, parading in the dark with slow solemnity, or with more startling speed: few images have managed, in the history of car design, to coincide so firmly with the very identity of a brand. And this is what Friuli-born Bruno Sacco has done with Mercedes: having become head of design for the Stuttgart-based company in 1975, after more than 15 years working in the style division together with Paul Bracq – who had penned icons such as the 280 SL “Pagoda” – Sacco has redefined the visual identity of the Mercedes range, imprinting it with a unique uniformity of language capable of evolving over the years. The ribbed rear lights, the wide fronts and the taut, rational lines: in 25 years of Sacco's direction, world would find them on models that would soon become legendary, such as the SL spider (R129), the S-class flagship, and the 190 (W201) that revolutionized automotive references of 1980s middle classes. It was precisely in March 1986 that Sacco, himself not prone to any design celebrity behavior, met Domus for a conversation where identity and continuity would be discussed: we published this exchange on issue 670.

Conversing with Bruno Sacco

If we are to retrace an ideal path of design through Mercedes products since 1953 we must begin with the connection between continuity and renewal, between quotation from the past and projection into the future. We shall pause in particular to consider the identification of archetypal elements in Mercedes design.

It is impossible not to mention the Mercedes mock radiator, or the familiar star. Aside from these immediate features however, I’d like to stress certain other intrinsic design characteristics that distinguish the various models. Consider, for example, the entire lateral profile, with the peculiar line of its doors and windows. To go back to the radiator, this is undoubtedly a major marketing high light. But it is also an arguable one. I would be a strange designer if I suddenly abolished it. Nevertheless I shall question it every time a new model is designed. Not through an automatic dislike - common to al designers for anything that can’t be changed - but to allow an alternative course to be kept open all the time.

An important step in that direction was taken with the SEC model in 1981. Traditionally linked to the saloons, this should have mounted the mock radiator, whereas actually it has the smaller nose of a sports car. If we were to sum up these episodes in a concept, what it would boil down to would be a tendency to approach the new in the light of the whole history of Mercedes design. I like to describe this attitude as “looking back without anger”.Sarei uno strano designer se volessi di colpo abolirlo; tuttavia, lo rimetterò in discussione ogni qualvolta avrà inizio la progettazione di un nuovo modello, non per un aprioristico fastidio - comune a tutti i progettisti - per ciò che non si può cambiare, ma perché rimanga sempre aperta la possibilità di una strada alternativa. Un passo significativo in tale direzione è stato mosso con il modello Sec del 1981 che, tradizionalmente legato alle berline, avrebbe dovuto montare il finto radiatore, mentre adotta il musetto delle vetture sportive. Se volessimo generalizzare questi episodi in un concetto ne risulterebbe la tendenza a costruire il nuovo tenendo presente l’intera storia del design Mercedes. Mi piace definire questo atteggiamento: “uno sguardo all’indietro senza rabbia”.

The designer’s “signature” is a very recent aspect of the auto industry. At Mercedes, however, the policy is one of identification between designers and the company...

In effect, the “signed” car phenomenon has been unknown at Mercedes up till now - and I believe it will stay that way! In my opinion, too much emphasis on original design shows the lack of a solid previous image. This has always been my line when answering people who ask me why we never accepted outside proposals and contributions. It just wouldn’t be possible. A designer’s hand can always be recognized. What’s more, the individual designer seldom manages to understand the intrinsic qualities of the product which he has been asked to design, or to “dress”. At Mercedes we try instead to look at the question as a set of interdependent functions. Our design is justified in the display of function.

Actually, I wonder whether this message is generally received and whether the consumer does really recognize the functions inherent in each detail. So being innovative does not necessarily mean inventing something absolutely new. Design is not stylism. In general, we have to recognize unfortunately that there is now a marked sameness of image in the car industry. This is not due, as people generally believe, or at least not completely, to basic technical processes. Even the wind tunnel, although it curbs the designer’s freedom a little, does not really limit the design. The tunnel simply tells us whether the car is aerodynamically good. A purely functionalistic outlook falls apart as soon as two different concepts of form both prove valid after checking. So you see, our position can be defined as one of “extended functionalism”, which means remembering that design also has to do with “sensual” factors. In other words we can accept that certain general rules are by now valid for projection. One of these is certainly the wedge shape. For clearly aerodynamic reasons, in fact lines with a marked horizontal progress do not seem to make sense any more. That however, is as far as functional restraints go. The designer’s research continues into the definition of a new form. The lucky thing about Mercedes is that unlike many car makers or individual car designers, the likelihood of having to work on more than one project per year has never arisen. To conclude, I do not believe, at any rate as far as we are concerned, that any real uniformization of the automobile-object will occur.

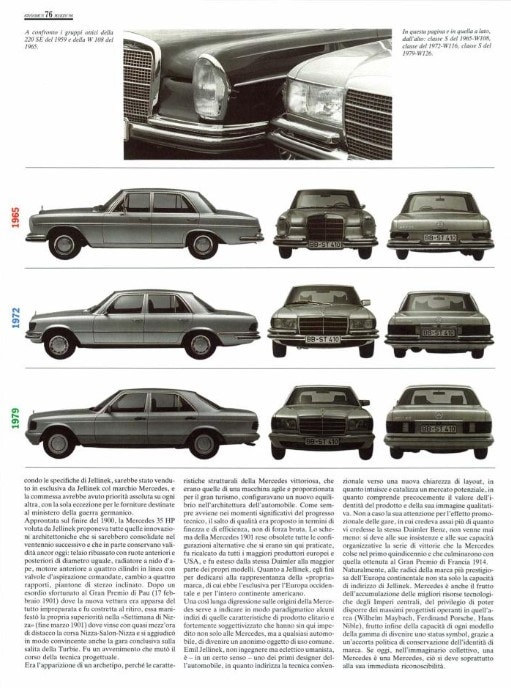

The Mercedes-Benz design philosophy avoids the abrupt demarcation lines which from one day to the next can make a previous model out-of-date.

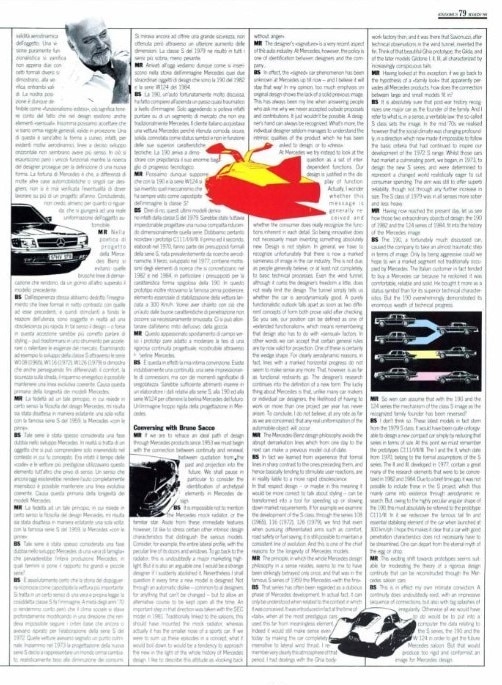

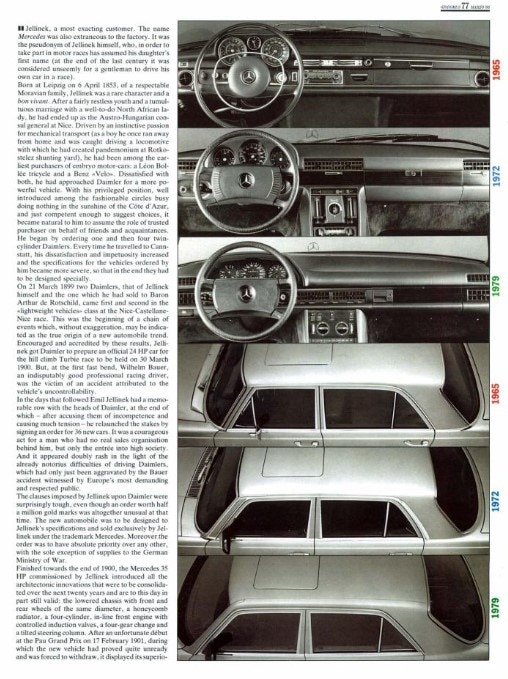

In fact we learned from experience that formal lines in sharp contrast to the ones preceding them, and hence basically tending to stimulate user reactions, are in reality liable to a more rapid obsolescence. In that respect design - or maybe in this meaning it would be more correct to talk about styling - can be transformed into a tool for speeding up or slowing down market requirements. If for example we examine the development of the S class, through the series 108 (1965), 116 (1972), 126 (1979), we find that even when pursuing differentiated aims such as comfort, road safety or fuel saving it is still possible to maintain a consistent line of evolution. And this is one of the chief reasons for the longevity of Mercedes models.

The principle, in which the whole Mercedes design philosophy in a sense resides, seems to me to have been strikingly betrayed only once, and that was in the famous S series of 1959 the Mercedes “with the fins”.

That series has often been regarded as a dubious phase of Mercedes development In actual fact, it can only be understood when related to the context in which it was conceived. It was introduced in fact at the time of “tails”, when all the most prestigious cars used this far from meaningless element. Indeed it would still make sense even today: by making the car completely insensitive to lateral wind thrust. I remember very clearly the atmosphere of that period. I had dealings with the Ghia body work factory then, and it was there that Savonuzzi, after technical observations in the wind tunnel, invented the fin. Think of that beautiful Ghia prototype, the Gilda, and of the later models Gildone I, II, III, all characterized by increasingly conspicuous tails.

Having looked at this exception, if we go back to the hypothesis of a “family look” that apparently per vades all Mercedes products, how does the connection between large and small models fit in?

It is absolutely sure that post-war history recognizes one major car as the founder of the family. And I refer to what is, in a sense, a veritable law: the so-called S class sets the image. In the mid-’70s we realised however that the social climate was changing profoundly, in a direction which now made it impossible to follow the basic criteria that had continued to inspire our development of the 1972 S range. Whilst those cars had market a culminating point, we began, in 1973, to design the new S series, and were determined to represent a changed world realistically eager to cut consumer spending. The aim was still to offer superb reliability, though not through any further increase in size. The S class of 1979 was in all senses more sober and less heavy.

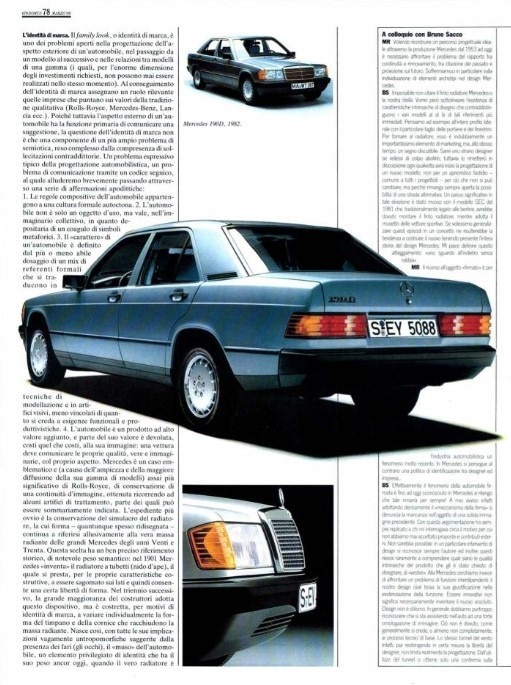

Having now reached the present day, let us see how those two extraordinary objects of design, the 190 of 1982 and the 124 series of 1984, fit into the history of the Mercedes image.

The 190, a fortunately much discussed car, caused the company to take an almost traumatic step in terms of image. Only by being aggressive could we hope to win a market segment not traditionally occupied by Mercedes. The Italian customer in fact tended to buy a Mercedes car because he reckoned it was comfortable, reliable and solid. He bought it more as a status symbol than for its superior technical characteristics. But the 190 overwhelmingly demonstrated its enormous wealth of technical progress.

So when can assume that with the 190 and the 124 series the mechanism of the class S image as the recognized family founder has been reversed?

I don’t think so. These latest models in fact stem from the 1979 S class. It would have been quite unforgivable to design a new compact car simply by reducing that series in terms of size. At this point we must remember the prototypes C111/I/II/III. The I and the II, which date from 1970, belong to the formal assumptions of the S series. The II and III, developed in 1977, contain a great many of the research elements that were to be concretized in 1982 and 1984. Due to a brief time gap, it was not possible to include these in the S project which thus mainly came into existence through aerodynamic re search. But owing to the highly peculiar angular shape of the 190, this must absolutely be referred to the prototype Clll/lll. In it we rediscover the famous tail fin and essential stabilizing element of the car when launched at 300 km/ph. I hope this makes it clear that a car with good penetration characteristics does not necessarily have to be streamlined. One can depart from the eternal myth of the egg or drop.

This exciting shift towards prototypes seems suitable for moderating the theory of a rigorous design continuity that can be reconstructed through the Mercedes saloon cars.

This is in effect my own intimate conviction. A continuity does undoubtedly exist, with an impressive sequence of connections, but also with big splashes of irregularity. Otherwise all we would have to do would be to put into a computer the data relating to the S series, the 190 and the W124 in order to get the future Mercedes saloon. But that would produce too rigid and conformist an image for Mercedes design.