After a manifesto project like the fire station on the Vitra campus – a deconstructivist landmark on a par with other contemporary works by Libeskind or Coop Himmelblau – Zaha Hadid was now the shining star of an era, the early 2000s, in which all reference designers had to be stars, star-architects. Her mark would become synonymous with a style and an approach to architecture based on the dialectics between sign and context, yet destined to give new meaning to the places where it was traced. The pavilion for the Regional Garden Exhibition, later codified as LF1, represents an expansion of Hadid’s research scope, on a much larger scale, working with the shape of the landscape and the “artificial nature” around: Domus published it 25 years ago, in July 1999, on issue 817.

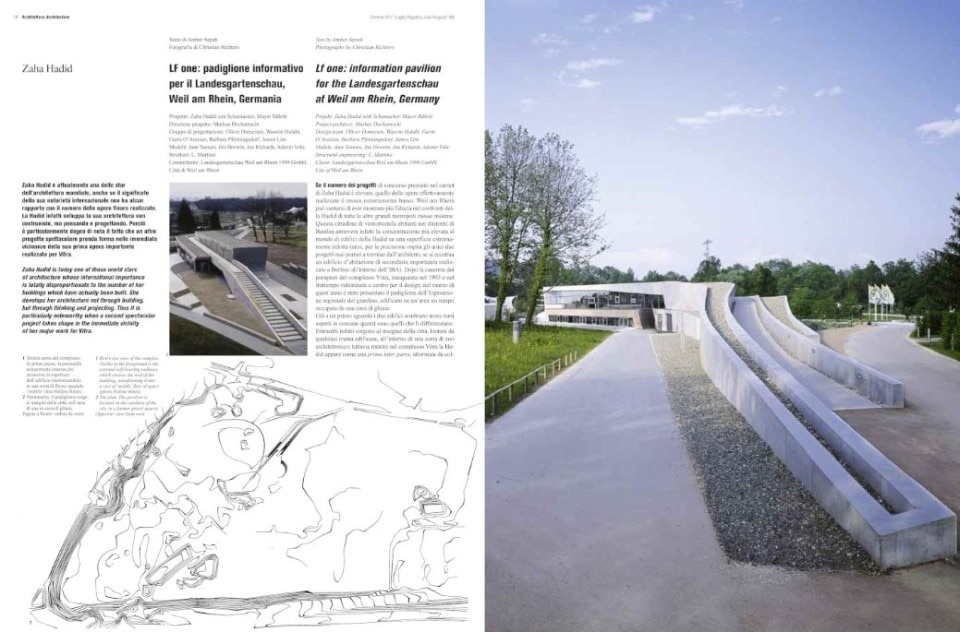

LF One: information pavilion for the Landesgartenschau at Weil Am Rhein, Germany

The number of award-winning competition entries in Zaha Hadid’s list of works is large, the number of buildings actually constructed, by contrast, notoriously small. Weil am Rhein can now boast of having shown Hadid more courage than all the major cities combined

This town of 28,000 inhabitants on the outskirts of Basle now has a higher concentration of Hadid buildings than anywhere else on Earth; to be precise, the only two of her designs ever actually built, apart from one insignificant apartment house in Berlin under the auspices of the IBA. Following the Fire Station in the Vitra complex, built in 1993 and since converted into a Design Center, the Regional Garden Show Pavilion, on the site of a former gravel pit, was handed over to the clients in March this year.

Not only at first sight do the two buildings appear to have as many common as they do contrasting features. In the one case as in the other, they are on the edge of town, well away from any ordinary building development, in a kind of architectural zoo. However, while in Vitra Hadid, surrounded by the works of such illustrious colleagues as Tadao Ando, Frank Gehry and Nicholas Grimshaw, comes across as prima inter pares, the Information Pavilion stands in the middle of a cabinet of curiosities including not only a medieval half-timbered house imported from Alsace, and a bulbous white tent, but also a rusty cement mixer dating from gravel-pit days and a Fun Bath on the edge of the Garden Show site.

Hadid’s building is unmistakable, though, maintaining its aloofness from its surroundings to assert with lofty ease its sovereignty over this land of architectural oddities.

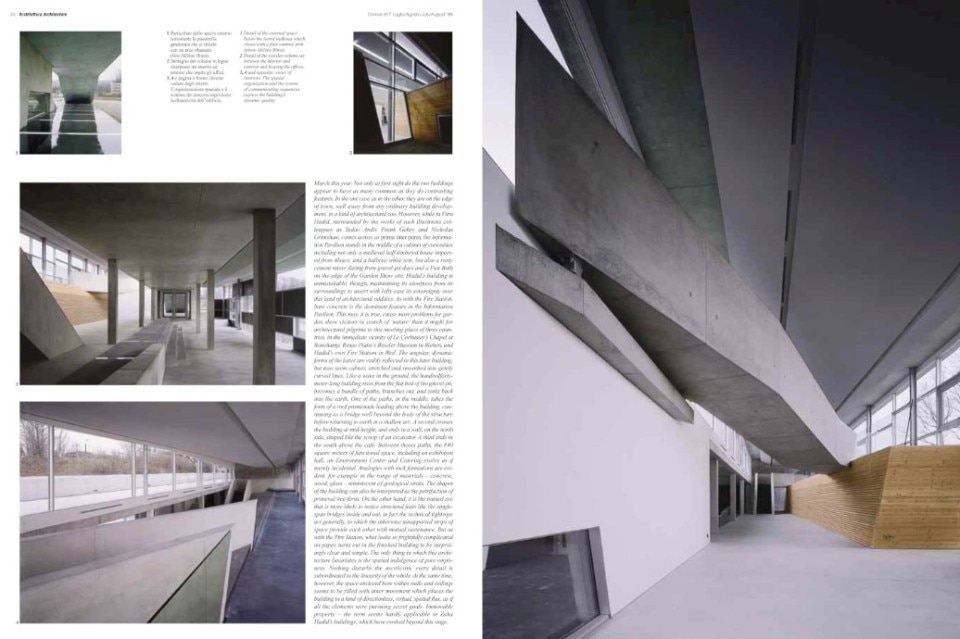

As with the Fire Station, bare concrete is the dominant feature in the Information Pavilion. This may, it is true, cause more problems for garden show visitors in search of ‘nature’ than it might for architectural pilgrims to this meeting-place of three countries, in the immediate vicinity of Le Corbusier’s Chapel at Ronchamp, Renzo Piano’s Beyeler Museum in Riehen, and Hadid’s own Fire Station in Weil.

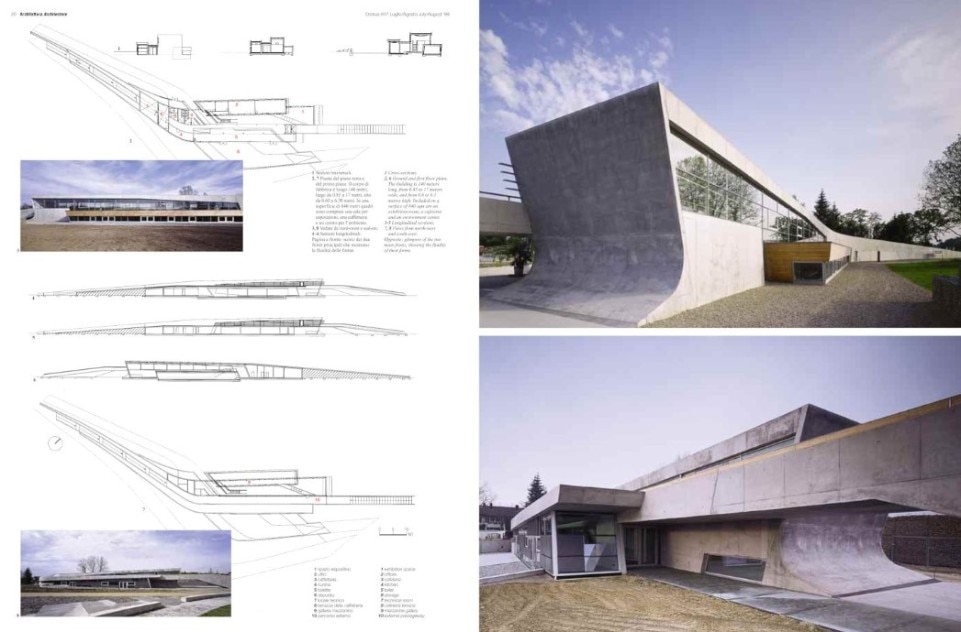

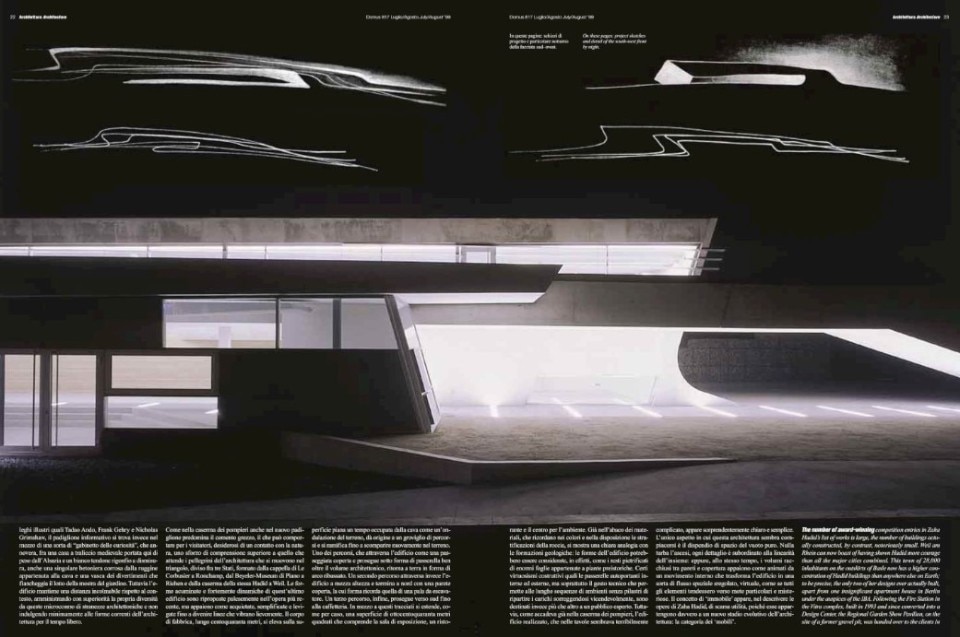

The angular, dynamic forms of the latter are visibly reflected in this later building, but now seem calmer, stretched and smoothed into gently curved lines. Like a wave in the ground, the hundredforty-meter-long building rises from the flat bed of the gravel pit, becomes a bundle of paths, branches out, and sinks back into the earth.

One of the paths, in the middle, takes the form of a roof promenade leading above the building, continuing as a bridge well beyond the body of the structure before returning to earth in a shallow arc. A second crosses the building at mid-height, and ends in a wall, on the north side, shaped like the scoop of an excavator. A third ends in the south above the café. Between theses paths, the 840 square meters of functional space, including an exhibition hall, an Environment Center and Catering evolve as if merely incidental

Analogies with rock formations are evident, for example in the range of materials – concrete, wood, glass – reminiscent of geological strata. The shapes of the building can also be interpreted as the petrifaction of primeval tree-ferns. On the other hand, it is the trained eye that is more likely to notice structural feats like the single-span bridges inside and out, in fact the technical tightrope act generally, in which the otherwise unsupported strips of space provide each other with mutual sustenance.

But as with the Fire Station, what looks so frightfully complicated on paper, turns out in the finished building to be surprisingly clear and simple. The only thing in which this architecture luxuriates is the spatial indulgence of pure emptiness. Nothing disturbs the asceticism, every detail is subordinated to the linearity of the whole. At the same time, however, the space enclosed here within walls and ceilings seems to be filled with inner movement which places the building in a kind of directionless, virtual, spatial flux, as if all the elements were pursuing secret goals. Immovable property – the term seems hardly applicable to Zaha Hadid’s buildings, which have evolved beyond this stage.

Opening image: Photo from Wikimedia Commons