125 years after the founding of Fabbrica Italiana Automobili Torino (Italian automobile factory in Turin), July 11th 1899, several worlds seem to have changed, more than just one; so much so that “Fiat” today is a brand, part of a large group, but its role through the short century, for Italy as for several other countries, has been as the role of an economic, political and, perhaps above all, cultural centre. It was the protagonist of mass Italian motorization after World War II with models such as the 500 and 600; before that, it had been the symbol of the modern condition, of 20th century Fordist industry – with its Lingotto plant that connecting it to Ford, where an enthusiastic Le Corbusier had his photo taken – then of its decline and transformation – with the Mirafiori plant but once again with the Lingotto, totally re-functionalised by Renzo Piano in two decades.

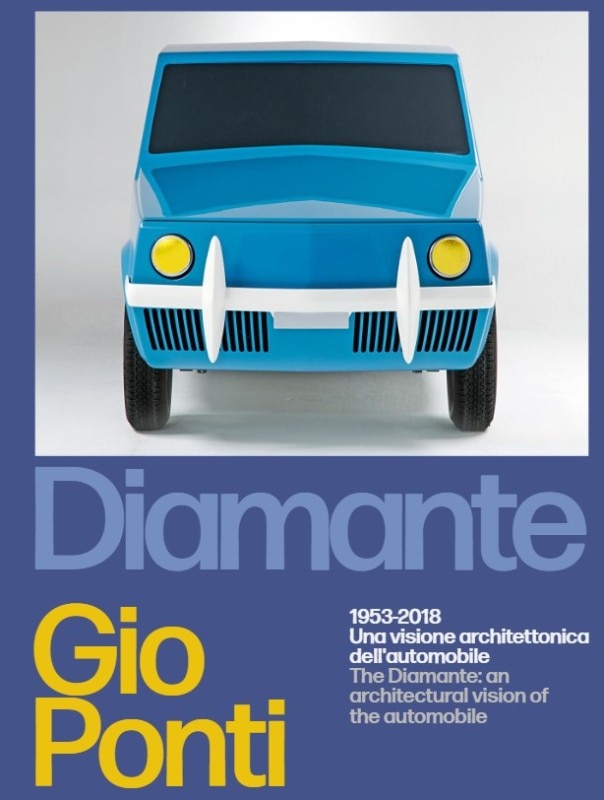

A long part of this road was also walked by Domus, which, as it turned 90 in 2018, had the chance to encounter all the know-how and design culture inherited from Fiat over more than a century, on the occasion of a true “cold case”. In partnership with Centro Stile and the Heritage division of what was by then Fiat Chrysler Automobiles – under the guidance of Roberto Giolito, designer of such milestones as the Multipla and the new 500 – the first 1:1 model of the Diamante, a “inhabitable” car that Gio Ponti had conceived in 1953, was made for the Grand Basel exhibition. A first, larger proposal was based on the Alfa Romeo 1900, but a smaller one had also been proposed to Fiat. However, time and priorities led in other directions, and the Diamante remained on paper. This is how Giolito recounted in October 2018, on Domus 1028, the “postponed” genesis of a model where all the enthusiasm of designing and making had once again been expressed, as it had been done for decades before.

An automotive breakaway

From Gio Ponti's drawings and notes, a life-size model of the Diamante was born, constructed in full respect of the spirit of the 1950s.

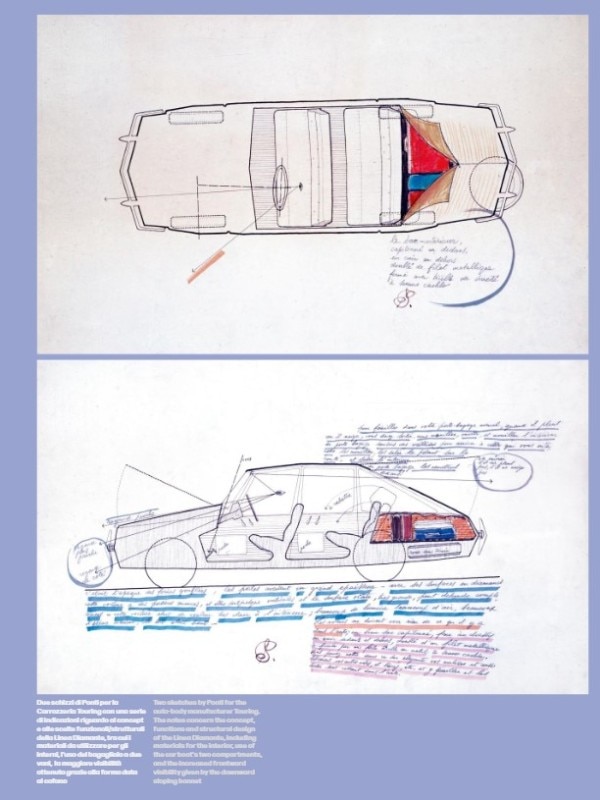

Gio Ponti imagined and designed an automobile from the users’ point of view. His study is not the umpteenth remake of a limited edition. Rather it is a set (or better, the envelope) of ideas aimed at improving the habitability and usability of the automobile. Ponti’s pragmatic approach is never self-referential, but aims to solve problems while avoiding certain conventions that were inadmissible to him, which he analysed by observing the fleet of cars on the road at the time.

The strong sense of newness of the diamond line is concentrated in the sides. They are slim and the windows less inclined than usual. Ponti creates a very low beltline (where the windscreen and windows meet the lower section) and reshapes the proportions of the side windows from horizontal to vertical. He eliminates the “shoulder” on the beltline, which on many cars back then bent outward at the base of the side windows to give an impression of robustness and protect against blows from the side. Doing so gave Ponti the possibility of cutting the doors and other moving parts in such a way as to create an unusual graphic composition. The eye follows the dividing lines traced on the almost flat surfaces much like it does when looking at a Mondrian painting.

The proportions are thus appreciated instead of being upstaged by light caressing the volumes, as seen in the automobile models that he considers “swollen”. The bonnet of the Diamante slopes downward, increasing visibility from the driver’s seat. Beneath a horizontal spine running over the middle of the doors, the car’s sides slant inward as they descend toward the ground. The entire bonnet is cut out of the body by a perimetral horizontal line, involving a small portion of the mudguards. This makes it one of the first enveloping bonnets in history, at least on paper – 20 years ahead of the Fiat 127 and the Saab 99.

The Diamante proposal is a coherent, organic, narratable whole – a modern automobile. It presents itself with the openness and generosity infused in the concept by a great designer.

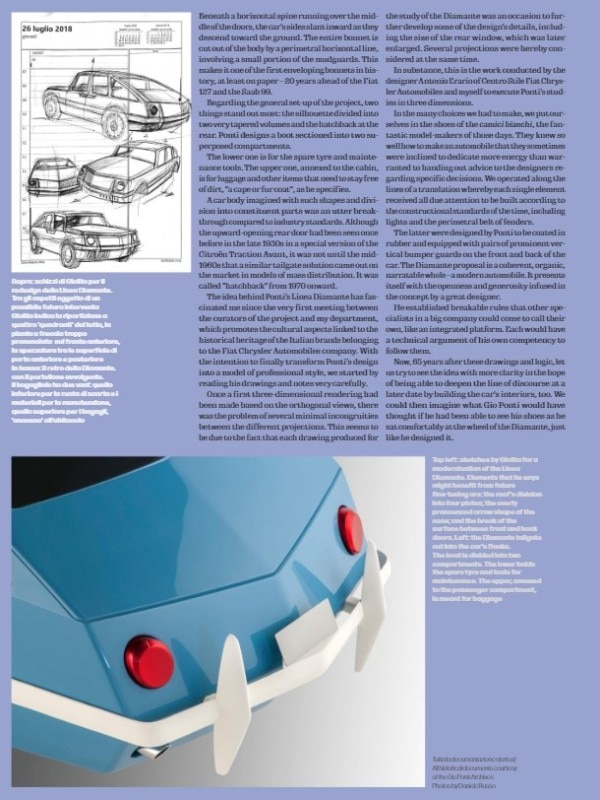

Regarding the general set-up of the project, two things stand out most: the silhouette divided into two very tapered volumes and the hatchback at the rear. Ponti designs a boot sectioned into two superposed compartments.

The lower one is for the spare tyre and maintenance tools. The upper one, annexed to the cabin, is for luggage and other items that need to stay free of dirt, “a cape or fur coat”, as he specifies.

A car body imagined with such shapes and division into constituent parts was an utter breakthrough compared to industry standards. Although the upward-opening rear door had been seen once before in the late 1930s in a special version of the Citroën Traction Avant, it was not until the mid-1960s that a similar tailgate solution came out on the market in models of mass distribution. It was called “hatchback” from 1970 onward.

The idea behind Ponti’s Linea Diamante has fascinated me since the very first meeting between the curators of the project and my department, which promotes the cultural aspects linked to the historical heritage of the Italian brands belonging to the Fiat Chrysler Automobiles company. With the intention to finally transform Ponti’s design into a model of professional style, we started by reading his drawings and notes very carefully.

Once a first three-dimensional rendering had been made based on the orthogonal views, there was the problem of several minimal incongruities between the different projections. This seems to be due to the fact that each drawing produced for the study of the Diamante was an occasion to further develop some of the design’s details, including the size of the rear window, which was later enlarged. Several projections were hereby considered at the same time.

In substance, this is the work conducted by the designer Antonio Erario of Centro Stile Fiat Chrysler Automobiles and myself to execute Ponti’s studies in three dimensions. In the many choices we had to make, we put ourselves in the shoes of the camici bianchi, the fantastic model-makers of those days. They knew so well how to make an automobile that they sometimes were inclined to dedicate more energy than warranted to handing out advice to the designers regarding specific decisions. We operated along the lines of a translation whereby each single element received all due attention to be built according to the constructional standards of the time, including lights and the perimetral belt of fenders.

The latter were designed by Ponti to be coated in rubber and equipped with pairs of prominent vertical bumper guards on the front and back of the car. The Diamante proposal is a coherent, organic, narratable whole – a modern automobile. It presents itself with the openness and generosity infused in the concept by a great designer.

He established breakable rules that other specialists in a big company could come to call their own, like an integrated platform. Each would have a technical argument of his own competency to follow them.

Now, 65 years after these drawings and logic, let us try to see the idea with more clarity in the hope of being able to deepen the line of discourse at a later date by building the car's interiors, too. We could then imagine what Gio Ponti would have thought if he had been able to see his shoes as he sat comfortably at the wheel of the Diamante, just like he designed it.