When he signed the Metabolism Manifesto at the Tokyo World Design Conference in 1960, projecting Japan onto the most radical front of the international architectural discourse, beyond the perimeter of brutalism and future High Tech, Fumihiko Maki already occupied a peculiar position, which he would develop for the rest of a long life. As radical his fellow signatories of the manifesto, Kiyonori Kikutake and Kisho Kurokawa – later author of the Nakagin Capsule Tower – as attentive he was to the forms of aggregation and settlement that came from traditional architecture. A pupil of Kenzo Tange, after an American stint at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, Maki would found his practice Maki & Associates in 1965, with which he would embody decade after decade the outlook of Japanese architecture on global themes and trends; global would also become the dimension of his work, among the many public and private buildings completed in Japan, and the iconic ones completed worldwide, such as the rebuilt Four World Trade Center in New York, which opened in 2013. A lecturer for years, he would then win the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1993, the second Japanese awardee after his mentor Tange.

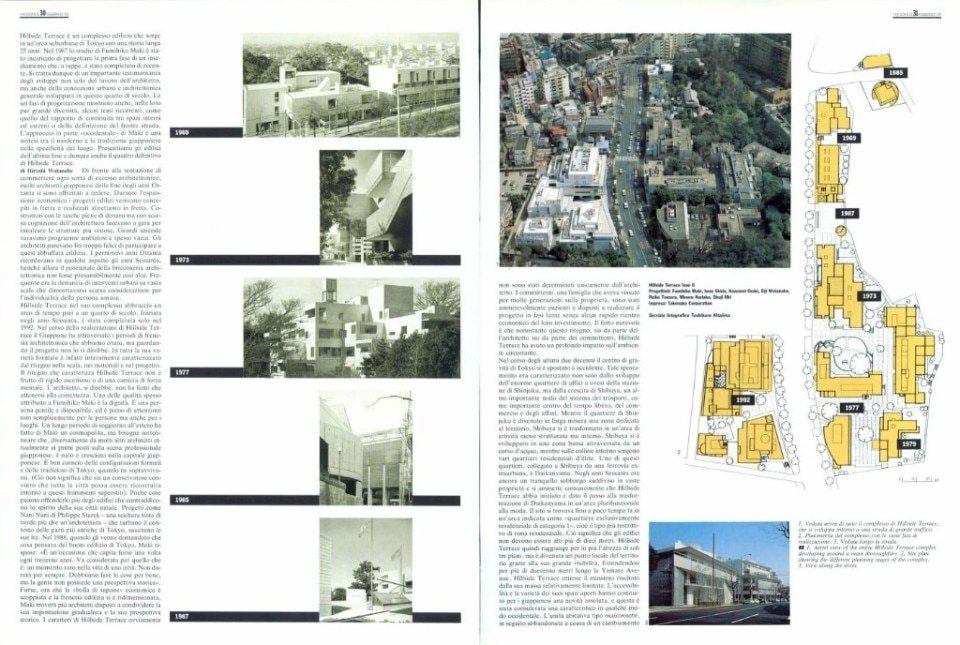

One project in Maki’s career, developed in three phases over three decades since 1962, can better outline the evolution of his language and inspiration in architecture making, up to that combination of technological innovation and local design principles – such as a balance between solid opacity and transparency somewhat critical of the International Style – that had been enriching the architect's practice since the 1960s. Domus published this project, the Hillside Terrace, in the aftermath of its completion, on issue 896 of February 1993.

Hillside Terrace, Tokyo

Hillside Terrace is a housing and commercial complex located in a suburban area of Tokyo, with a 25-year-old history. In 1967 Fumihiko Maki’s office was appointed to design phase 1 of an estate the final phase of which was recently completed. It is thus an important testimony to the developments not only of the architect’s work, but of general urban and architectural concepts developed over the last quarter of a century.

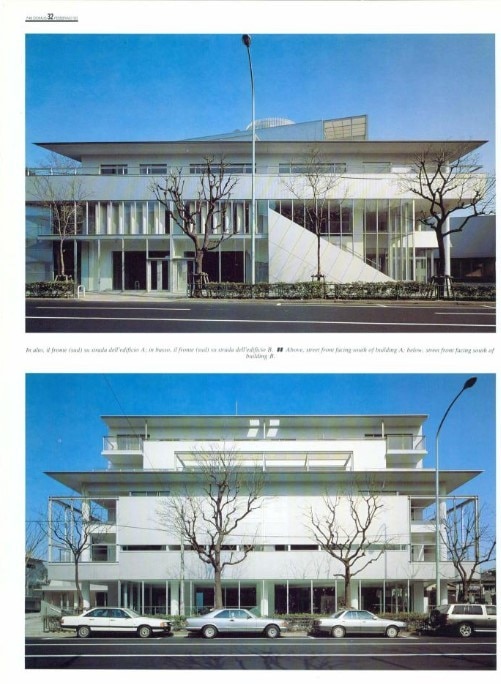

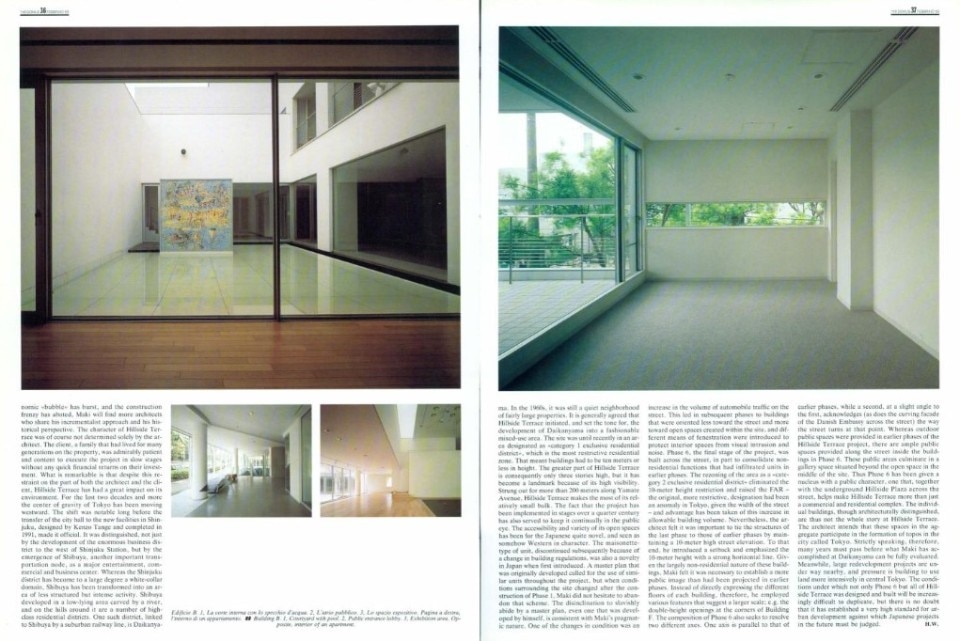

The six design phases, though widely different, show a number of leitmotifs such as a continuity between interior and exterior spaces or the definition of street frontage. Maki’s partly “western” approach is a synthesis of the modern and of Japanese tradition in the specificness of place. Published here are the buildings in the last phase and hence also the final picture of Hillside Terrace.

Faced with the temptation to commit all manner of architectural excess, many Japanese architects in the late 1980s succumbed with alacrity. As the economy expanded, building projects were hastily conceived and as hastily implemented. Developers with money in their pockets but little knowledge of architecture competed in putting up the most eye-catching structures. Large enterprises floated ambitious and often fatuous schemes.

Architects seemed only too happy to participate in this building binge. The go-go 1980s were reminiscent in some ways of the 1960s, though the potential for architectural mischief then was arguably not as great. Large-scale urban intervention demonstrating little consideration of the individual human being was frequently advocated.

Hillside Terrace in its entirety spans a quarter century. Started in the 1960s, it was completed only in 1992. While Hillside Terrace was being built, Japan went through the two above-mentioned periods of architectural immoderation, but one would not know it from looking at the project.

Decorum is one of the qualities often ascribed to Fumihiko Maki. He is urbane and courteous, and he is solicitous about not merely persons but places.

For all its formal variety, it is characterized throughout by restraint in scale, material and design. The restraint that characterizes Hillside Terrace is not the product of a dour asceticism or some mental straightjacket. The architect, one might say, has merely observed the proprieties. Decorum is one of the qualities often ascribed to Fumihiko Maki. He is urbane and courteous, and he is solicitous about not merely persons but places. His long sojourn abroad has made Maki a cosmopolitan, but it should be noted that unlike many other architects currently prominent in the Japanese architectural scene, he was born and raised in the Japanese capital.

He is mindful of Tokyo’s patterns and traditions, where they survive. (That is not to say that he is a conservative who believes that the entire city can be rebuilt around such surviving fragments.) Few things seem to offend him more than buildings that run counter to the spirit of his native city. Projects like Philippe Starck’s Nani Nani - more a green-colored sculpture than architecture - that disturb the context of older parts of Tokyo draw his ire. Asked in 1988 how he felt about the building boom in Tokyo, Maki replied: “It’s a chance that comes along once in maybe 300 years. It has to be seen for what it is: a rare moment in time for a city. It’s not going to last forever. We ought to do things properly, but people don’t have a historical perspective”.

Perhaps now that the economic “bubble” has burst, and the construction frenzy has abated, Maki will find more architects who share his incrementalist approach and his historical perspective. The character of Hillside Terrace was of course not determined solely by the architect. The client, a family that had lived for many generations on the property, was admirably patient and content to execute the project in slow stages without any quick financial returns on their investment. What is remarkable is that despite this restraint on the part of both the architect and the client, Hillside Terrace has had a great impact on its environment.

For the last two decades and more the center of gravity of Tokyo has been moving westward. The shift was notable long before the transfer of the city hall to the new facilities in Shinjuku, designed by Kenzo Tange and completed in 1991, made it official. It was distinguished, not just by the development of the enormous business district to the west of Shinjuku Station, but by the emergence of Shibuya, another important transportation node, as a major entertainment, commercial and business center. Whereas the Shinjuku district has become to a large degree a white-collar domain, Shibuya has been transformed into an area of less structured but intense activity. Shibuya developed in a low-lying area carved by a river, and on the hills around it are a number of high-class residential districts. One such district, linked to Shibuya by a suburban railway line, is Daikanyama.

In the 1960s, it was still a quiet neighborhood of fairly large properties. It is generally agreed that Hillside Terrace initiated, and set the tone for, the development of Daikanyama into a fashionable mixed-use area. The site was until recently in an area designated as «category 1 exclusive residential district», which is the most restrictive residential zone. That meant buildings had to be ten meters or less in height. The greater part of Hillside Terrace is consequently only three stories high, but it has become a landmark because of its high visibility. Strung out for more than 200 meters along Yamate Avenue, Hillside Terrace makes the most of its relatively small bulk. The fact that the project has been implemented in stages over a quarter century has also served to keep it continually in the public eye.

The accessibility and variety of its open spaces has been for the Japanese quite novel, and seen as somehow Western in character. The maisonette-type of unit, discontinued subsequently because of a change in building regulations, was also a novelty in Japan when first introduced. A master plan that was originally developed called for the use of similar units throughout the project, but when conditions surrounding the site changed after the construction of Phase 1, Maki did not hesitate to abandon that scheme.

The disinclination to slavishly abide by a master plan, even one that was developed by himself, is consistent with Maki’s pragmatic nature. One of the changes in condition was an increase in the volume of automobile traffic on the street. This led in subsequent phases to buildings that were oriented less toward the street and more toward open spaces created within the site, and different means of fenestration were introduced to protect interior spaces from visual intrusion and noise.

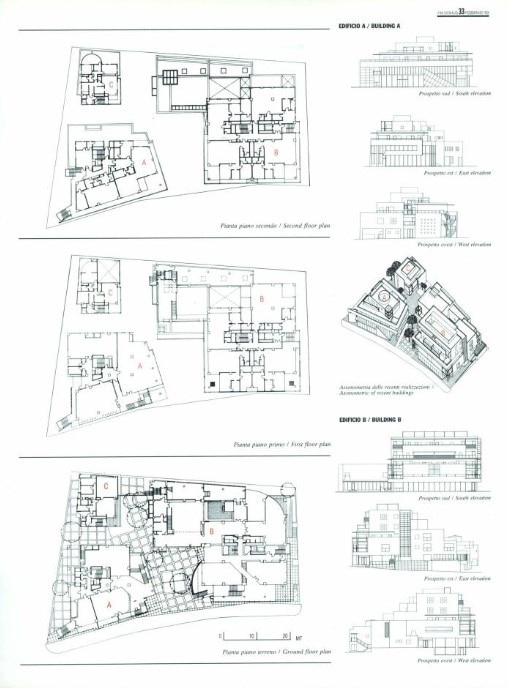

Phase 6, the final stage of the project, was built across the street, in part to consolidate nonresidential functions that had infiltrated units in earlier phases. The rezoning of the area as a “category 2 exclusive residential district” eliminated the 10-meter height restriction and raised the FAR - the original, more restrictive, designation had been an anomaly in Tokyo, given the width of the street - and advantage has been taken of this increase in allowable building volume. Nevertheless, the architect felt it was important to tie the structures of the last phase to those of earlier phases by maintaining a 10-meter high street elevation.

To that end, he introduced a setback and emphasized the 10-meter height with a strong horizontal line. Given the largely non-residential nature of these buildings, Maki felt it was necessary to establish a more public image than had been projected in earlier phases. Instead of directly expressing the different floors of each building, therefore, he employed various features that suggest a larger scale; e.g. the double-height openings at the corners of Building F. The composition of Phase 6 also seeks to resolve two different axes.

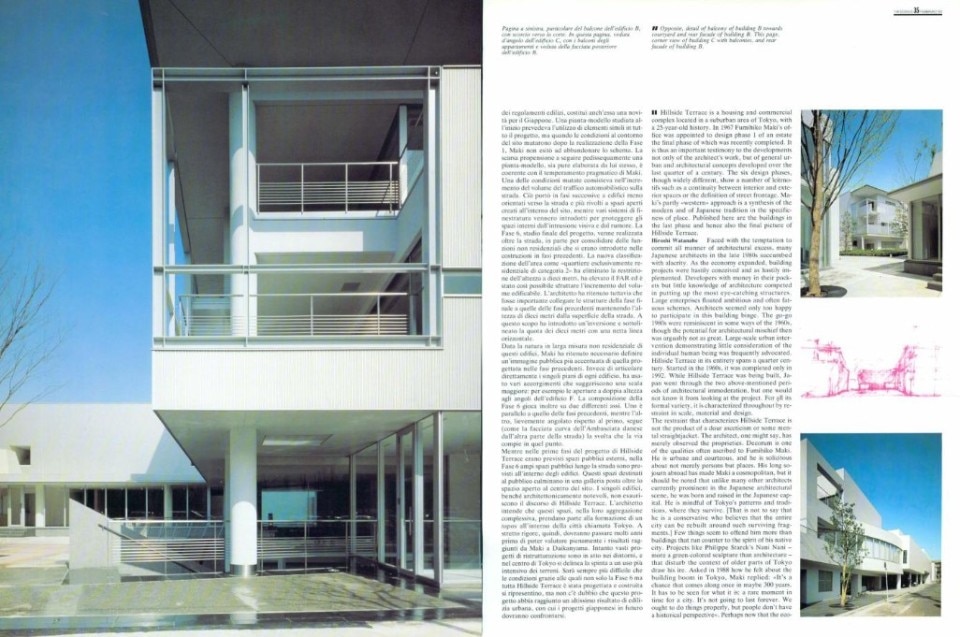

One axis is parallel to that of earlier phases, while a second, at a slight angle to the first, acknowledges (as does the curving facade of the Danish Embassy across the street) the way the street turns at that point. Whereas outdoor public spaces were provided in earlier phases of the Hillside Terrace project, there are ample public spaces provided along the street inside the buildings in Phase 6.

These public areas culminate in a gallery space situated beyond the open space in the middle of the site. Thus Phase 6 has been given a nucleus with a public character, one that, together with the underground Hillside Plaza across the street, helps make Hillside Terrace more than just a commercial and residential complex. The individual buildings, though architecturally distinguished, are thus not the whole story at Hillside Terrace. The architect intends that these spaces in the aggregate participate in the formation of topos in the city called Tokyo. Strictly speaking, therefore, many years must pass before what Maki has accomplished at Daikanyama can be fully evaluated. Meanwhile, large redevelopment projects are under way nearby, and pressure is building to use land more intensively in central Tokyo.

The conditions under which not only Phase 6 but all of Hillside Terrace was designed and built will be increasingly difficult to duplicate, but there is no doubt that it has established a very high standard for urban development against which Japanese projects in the future must be judged.