At the end of the 1970s, the vast quadrant created by the clearance of the former slaughterhouses, in a north-eastern part of pre-gentrification Paris that was still an area of delicate balances, if not open social tension, became the first and most intense field of confrontation between two visions of the city: that of the newly elected president, François Mitterrand, and that of his predecessor. The 1982 competition for the Parc de la Villette was a key event in both the Grands Projets, with which Mitterrand transformed the landscape of the city, and the history of contemporary architecture. One of the candidate projects, proposed by Rem Koolhaas, is almost more famous than the winner itself for its scope as a theoretical manifesto; still, what was to be built over the course of a decade, completed in 1999 with the construction of the last fiery red sculptural building, the last foil to punctuate a complex and layered project, is a park born from a spatial structure conceived by Bernard Tschumi and developed as a choral reflection, further conceptualised by the contributions of philosopher Jacques Derrida, designed for the participation of Dan Flavin, Rebecca Horn, Gaetano Pesce, and completed by interventions at all possible scales, signed by names such as Jean Nouvel and Philippe Starck.

Above all, it is a place that would breathe a fresh, not hostile, air into an area of the city where cultural hybridization could become a resource, as François Chaslin remarked when he visited it with Domus, and told us in July 1999, on issue 817.

Parc de la Villette, Paris

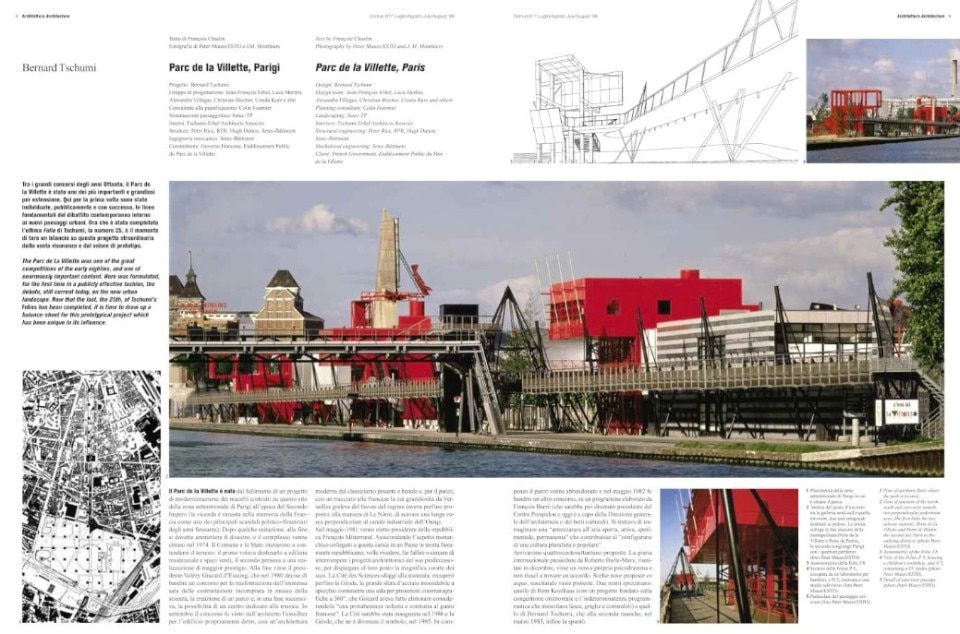

The Parc de La Villette was one of the great competitions of the early eighties, and one of enormously important content. Here was formulated, for the first time in a publicly effective fashion, the debate, still current today, on the new urban landscape. Now that the last, the 25th, of Tschumi’s Folies has been completed, it is time to draw up a balance-sheet for this prototypical project which has been unique in its influence.

There ensued a tug-of-war between the City Council and the State over what to do with the property. The former wanted it earmarked for public housing and parkland, the latter had grander schemes in mind. In the end President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing got his way. In 1980 he decided to announce a competition for the transformation of the immense, unfinished bargaining hall into a science museum, for the creation of a park and, at a later stage, of a music center.

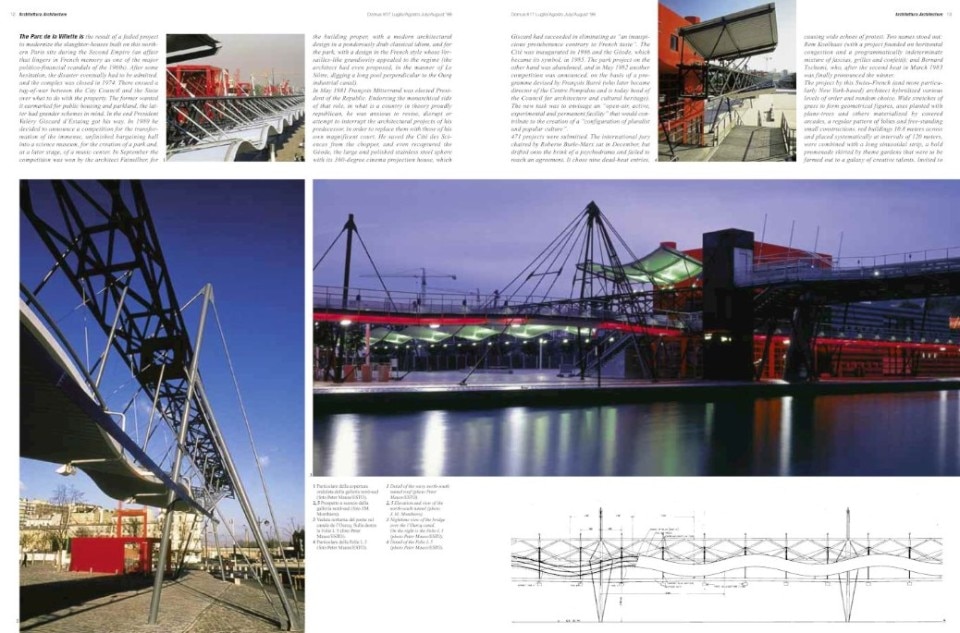

In September the competition was won by the architect Fainsilber, for the building proper, with a modern architectural design in a ponderously drab classical idiom, and for the park, with a design in the French style whose Versailles-like grandiosity appealed to the regime (the architect had even proposed, in the manner of Le Nôtre, digging a long pool perpendicular to the Ourq industrial canal). In May 1981 François Mitterrand was elected President of the Republic.

Endorsing the monarchical side of that role, in what is a country in theory proudly republican, he was anxious to revise, disrupt or attempt to interrupt the architectural projects of his predecessor, in order to replace them with those of his own magnificent court. He saved the Cité des Sciences from the chopper, and even recaptured the Géode, the large and polished stainless steel sphere with its 360-degree cinema projection house, which Giscard had succeeded in eliminating as “an inauspicious protuberance contrary to French taste”. The Cité was inaugurated in 1986 and the Géode, which became its symbol, in 1985.

The park project on the other hand was abandoned, and in May 1982 another competition was announced, on the basis of a programme devised by François Barré (who later became director of the Centre Pompidou and is today head of the Council for architecture and cultural heritage). The new task was to envisage an “open-air, active, experimental and permanent facility” that would contribute to the creation of a “configuration of pluralist and popular culture”.

471 projects were submitted. The international jury chaired by Roberto Burle-Marx sat in December, but drifted onto the brink of a psychodrama and failed to reach an agreement. It chose nine dead-heat entries, causing wide echoes of protest. Two names stood out: Rem Koolhaas (with a project founded on horizontal congestion and a programmatically indeterminate mixture of fascias, grilles and confetti); and Bernard Tschumi, who, after the second heat in March 1983 was finally pronounced the winner.

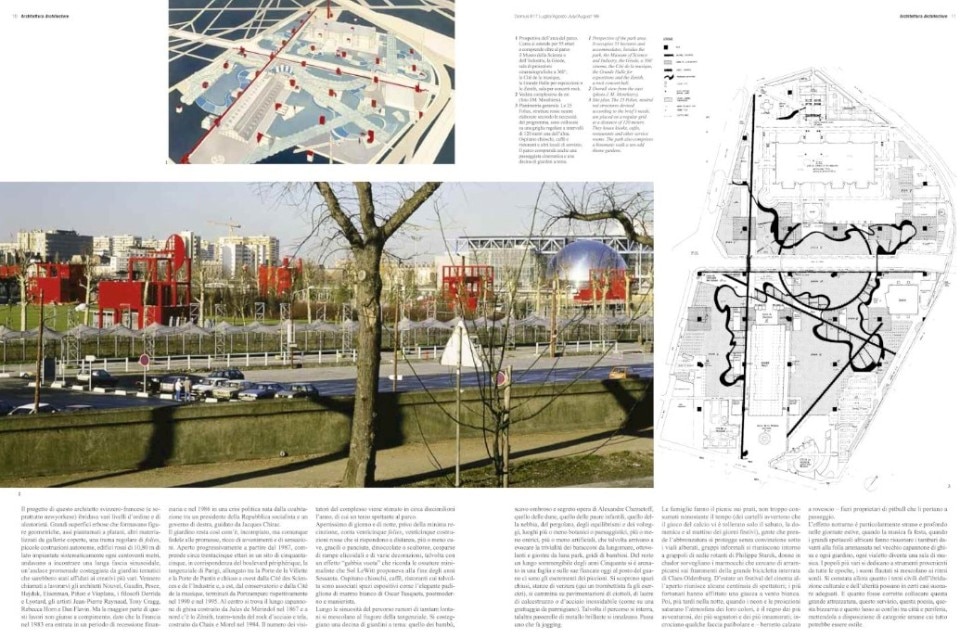

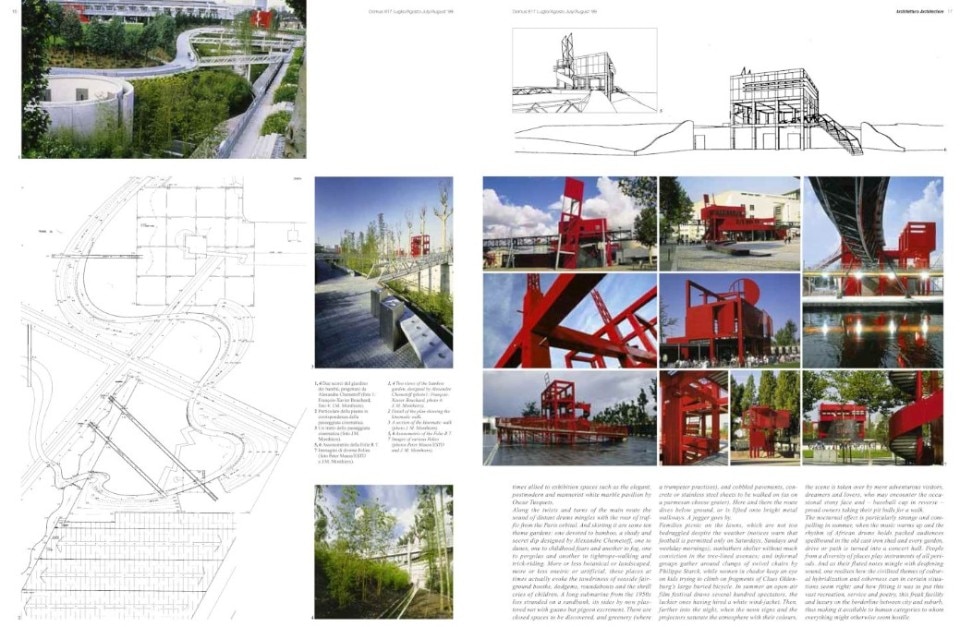

The project by this Swiss-French (and more particularly New York-based) architect hybridized various levels of order and random choice. Wide stretches of grass to form geometrical figures, axes planted with plane-trees and others materialized by covered arcades, a regular pattern of folies and free-standing small constructions, red buildings 10.8 meters across and placed systematically at intervals of 120 meters, were combined with a long sinusoidal strip, a bold promenade skirted by theme gardens that were to be farmed out to a galaxy of creative talents.

471 projects were submitted. The international jury drifted onto the brink of a psychodrama and failed to reach an agreement. It chose nine dead-heat entries, causing wide echoes of protest. Two names stood out: Rem Koolhaas and Bernard Tschumi, who, after the second heat in March 1983 was finally pronounced the winner.

Invited to work on these were the architects Nouvel, Gaudin, Pesce, Hejduk, Eisenman, Piñon and Viaplana, the philosophers Derrida and Lyotard, the artists Jean-Pierre Raynaud, Tony Cragg, Rebecca Horn and Dan Flavin. But most of these projects were not carried through, because in 1983 France went into recession and in 1986 into a political crisis, triggered by the cohabitation of a socialist president of the Republic with a right-wing government under Jacques Chirac.

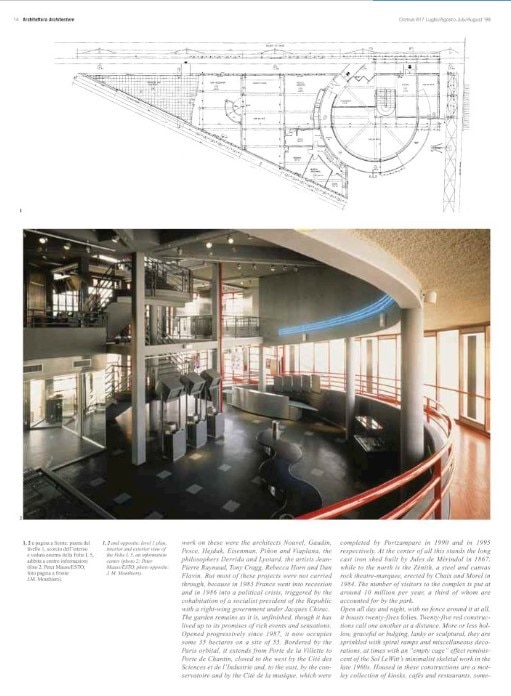

The garden remains as it is, unfinished, though it has lived up to its promises of rich events and sensations. Opened progressively since 1987, it now occupies some 35 hectares on a site of 55. Bordered by the Paris orbital, it extends from Porte de la Villette to Porte de Chantin, closed to the west by the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie and, to the east, by the conservatoire and by the Cité de la musique, which were completed by Portzamparc in 1990 and in 1995 respectively.

At the center of all this stands the long cast iron shed built by Jules de Mérindol in 1867, while to the north is the Zénith, a steel and canvas rock theatre-marquee, erected by Chaix and Morel in 1984. The number of visitors to the complex is put at around 10 million per year, a third of whom are accounted for by the park.

Open all day and night, with no fence around it at all, it boasts twenty-fives folies. Twenty-five red constructions call one another at a distance. More or less hollow, graceful or bulging, lanky or sculptural, they are sprinkled with spiral ramps and miscellaneous decorations, at times with an “empty cage” effect reminiscent of the Sol LeWitt’s minimalist skeletal work in the late 1960s. Housed in these constructions are a motley collection of kiosks, cafés and restaurants, some-times allied to exhibition spaces such as the elegant, postmodern and mannerist white marble pavilion by Oscar Tusquets.

The project by this Swiss-French (and more particularly New York-based) architect hybridized various levels of order and random choice.

Along the twists and turns of the main route the sound of distant drums mingles with the roar of traffic from the Paris orbital. And skirting it are some ten theme gardens: one devoted to bamboo, a shady and secret dip designed by Alexandre Chemetoff, one to dunes, one to childhood fears and another to fog, one to pergolas and another to tightrope-walking and trick-riding. More or less botanical or landscaped, more or less oneiric or artificial, these places at times actually evoke the tawdriness of seaside fairground booths, dodgems, roundabouts and the shrill cries of children.

A long submarine from the 1950s lies stranded on a sandbank, its sides by now plastered not with guano but pigeon excrement. There are closed spaces to be discovered, and greenery (where a trumpeter practises), and cobbled pavements, concrete or stainless steel sheets to be walked on (as on a parmesan cheese grater). Here and there the route dives below ground, or is lifted onto bright metal walkways. A jogger goes by.

Families picnic on the lawns, which are not too bedraggled despite the weather (notices warn that football is permitted only on Saturdays, Sundays and weekday mornings); sunbathers shelter without much conviction in the tree-lined avenues; and informal groups gather around clumps of swivel chairs by Philippe Starck, while women in chador keep an eye on kids trying to climb on fragments of Claes Oldenburg’s large buried bicycle. In summer an open-air film festival draws several hundred spectators, the luckier ones having hired a white wind-jacket.

Then, further into the night, when the neon signs and the projectors saturate the atmosphere with their colours, the scene is taken over by more adventurous visitors, dreamers and lovers, who may encounter the occasional stony face and – baseball cap in reverse – proud owners taking their pit bulls for a walk. The nocturnal effect is particularly strange and compelling in summer, when the music warms up and the rhythm of African drums holds packed audiences spellbound in the old cast iron shed and every garden, drive or path is turned into a concert hall. People from a diversity of places play instruments of all periods.

And as their fluted notes mingle with deafening sound, one realises how the civilised themes of cultural hybridization and otherness can in certain situations seem right; and how fitting it was to put this vast recreation, service and poetry, this freak facility and luxury on the borderline between city and suburb, thus making it available to human categories to whom everything might otherwise seem hostile.