In the cultural landscape of architecture, a sequence from a film by Ila Beka and Louise Lemoine has become famous in the last 15 years, where the housekeeper of a contemporary house literally emerges from a portion of the floor raised by a piston. The house is the one that Rem Koolhaas / OMA, together with former Arup Deputy Chairman engineer Cecil Balmond, designed in Floirac, near Bordeaux. It is one of those Koolhaas buildings that became manifestos immediately after his books, with its spatial, formal and – visibly – structural solutions, an instant subject of stories, and multiple revisitations. A story is exactly what Beatriz Colomina and Blanca Lleó crafted to explore and deconstruct the house and its meaning for Domus in January 1999, a storytelling dialogue that appeared on issue 811.

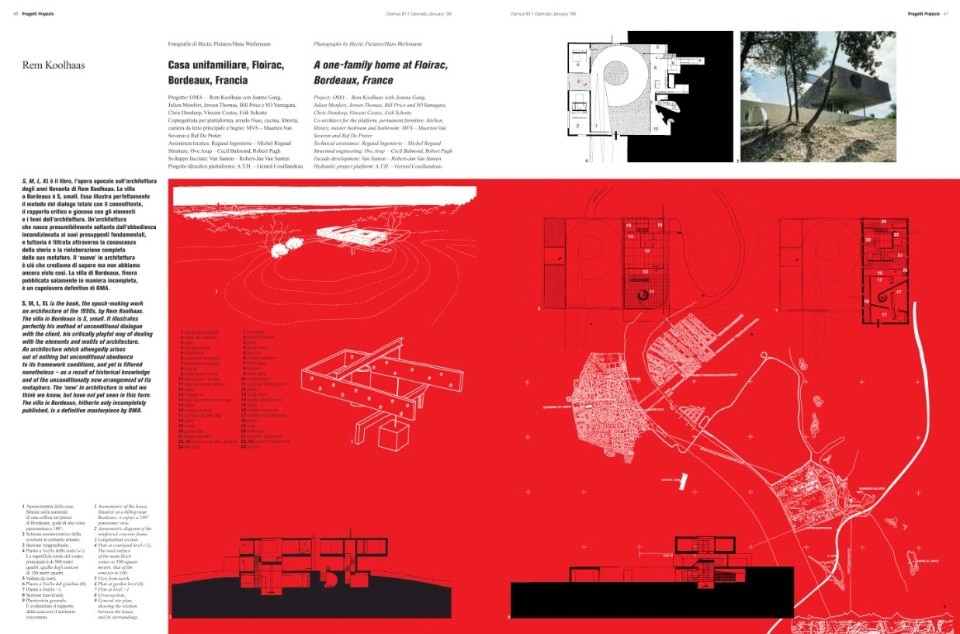

A one-family home at Floirac, Bordeaux, France

S, M, L, XL is the book, the epoch-making work on architecture of the 1990s, by Rem Koolhaas. The villa in Bordeaux is S, small. It illustrates perfectly his method of unconditional dialogue with the client, his critically playful way of dealing with the elements and motifs of architecture. An architecture which allwegedly arises out of nothing but unconditional obedience to its framework conditions, and yet is filtered nonetheless — as a result of historical knowledge and of the unconditionally new arrangement of its metaphors. The ‘new’ in architecture is what we think we know, but have not yet seen in this form. The villa in Bordeaux, hitherto only incompletely published, is a definitive masterpiece by OMA.

“A machine was its heart”, a house in Floirac

Her first serious attempt to see it was in the summer of 1997. They had been invited to a conference in Santander. She had accepted for sentimental reasons. Her mother, as a child, used to spend summers in Santander. She had never been there. She wanted to see it. At the same time, the occasion filled her with ambivalence. It was always like that whenever she had to do something adult in her country. Spain was all right for vacations. From the moment they accepted the invitation, she kept plotting ways in which she could get out of Santander. A side trip, an excursion, something that would take away that feeling of claustrophobia she was almost certain to get. She saw Bordeaux on a map and convinced him that, even if they had only a day and a half to go and come back, nine hundred kilometers to see a house was not that bad. Everything else was against her. ETA had just killed somebody and there were demonstrations everywhere. Traffic through the Basque country collapsed. Now they were stuck. He did not seem to mind: “Santander is so beautiful – you didn’t say it was so beautiful – the food is so good, the wine is so good.” Spain always had this effect on him. It turned him into an hedonist. She thought, one should never agree to do anything in one’s own country

A few months later, she did it again. She had agreed to take part in a conference in Zaragoza. There was no way she could pretend to be on vacation in Zaragoza in November. Even before arriving there, she was plotting ways to get out. Inevitably, she saw Bordeaux on a map. It had by now become an obsession. She convinced Blanca, who was speaking at the same conference, to travel with her. She knew she would be good company. They left the evening after their lectures, skipping the dinner and driving through the night, like fugitives. It was exhilarating, it reminded her of other times. She wanted to go to the frontier but on the way they settled for San Sebastián. “The food is always good,” Blanca said, and then remembered a hotel on the bay she had once been to with a lover many years ago. Anyway, San Sebasti·n is already another country. In the morning they left for Bordeaux after seeing the two slanted cubes of Moneo’s Kursaal under construction. “It has got to be his most radical building,” they agreed. “If only it could be made to look like the model.”

Bordeaux. They checked into Nouvel’s Hotel St. James in Floirac, which was very cool. It had raised beds – like Le Corbusier’s – so that laying on one was like floating in the landscape out of the corner horizontal window that overlooked the long, thin, black pool. They were very excited. They had a coffee and drove up to the house.

It was Sunday afternoon. The owners had visitors. A young boy came to meet them outside the house where they had parked. Only much later they realized she was a girl, the youngest of the couple’s children. The woman was in the courtyard. She was covered in mud as if she had been gardening. They didn’t see any garden. She greeted them in Spanish, invited them in and offered coffee and cake. They went upstairs to meet the man who was in the glass house sitting at the dining table with the visitors. He spoke Spanish. He once had business with the Basque country. He offered them a drink.

They couldn’t sit still very long. The light was so beautiful. It wouldn’t last and Blanca wanted to take pictures. They went outside. Their heads were spinning. They climbed up the hill outside the glass wall to see what was on the other side. Before they knew, they were up to their ankles in mud. It had rained heavily in the days before their visit. She found it amusing that Blanca was so agitated. She had heard her murmuring between shots: “How lucky to be such a good architect!” She had never heard anything like that coming out of an architect’s mouth. And how about herself? Why had she gone through such elaborate plans to see a house under construction? Not that she was not interested in contemporary work. But she never went after it with the same kind of zealousness she reserved for the mythical houses that populated her imagination – as when she blackmailed somebody to take her to the Tugendhat House in Brno after a lecture in Vienna, or to the Curruchet House in La Plata after a lecture in Buenos Aires, or to the Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, after a lecture in Chicago, or to E.1027 in Cap-Martin from Barcelona... She had gotten, without quite realizing it, into the habit of making it a condition every time she had to lecture somewhere even remotely near an object of her desire. It was an incentive that she was sure improved her performance.

She didn’t even intend to write about the house in Floirac. She never wrote about contemporary work. She detested what they called criticism. The pretension that a critic contemporary with a work could interpret it in any meaningful way had become more and more unsustainable. And anyway, she tended to prefer the stories that architects tell to the pedantic language of critics. She wasn’t interested in taking pictures either (although she did, to keep the conversation with Blanca going). She always found more interesting the official shots, the way architects choose to represent their houses. She just wanted to see. But why?

Seduction came through a story, almost a ‘treatment,’ in the film industry sense of the term: “A couple lived in a very old, beautiful house in Bordeaux. Eight years ago, they wanted a new house, something very simple. They were looking at different architects. Then the husband had a car accident. He almost died, but he survived. Now he needs a wheelchair. Two years after the accident, the couple began to think about the house again. Now the new house could liberate the husband from the prison that their old house and the medieval city they lived in had become. ‘Contrary to what you would expect,’ he told the architect, ‘I do not want a simple house. I want a complex house, because the house will define my world.’” She had read the story somewhere. It touched her somehow. She couldn’t tell exactly why. It was as if it fed several of her fantasies, or darkest fears, as movies sometimes do. She wanted to see this movie. She was grateful to have been allowed on the set. She felt like a spy, a voyeur.

‘Contrary to what you would expect,’ he told the architect, ‘I do not want a simple house. I want a complex house, because the house will define my world.’

Upon reflection, she realized this was the way we are always allowed into OMA’s work, through a story. Before there were any buildings, Office for Metropolitan Architecture was launched with a novel, Delirious New York (a series of film clips in Charles Jencks’s reading), and as OMA started to build, Koolhaas (who was a script writer before he studied architecture at the AA) kept feeding us stories. It was always the houses that provoked the best scripts. In Villa dall’Ava, for example, there was the story of the client almost getting arrested in the airport when, while waiting for his architect, he got into a fight with a security guard. Sometimes the scripts were not even about an OMA house, as with The House That Made Mies, a fantasy about the Kröller-Müller House that is Koolhaas’s most intimate story. That was her favorite. Blanca thought that the best was still the one about the floating Moscow pool arriving in Manhattan at the end of Delirious New York. Maybe. But even that fantasy ended up as the roof of a house.

Blanca Lleó: Each one of my shoes weights at least five kilos.

Beatriz Colomina: I have the sensation of carrying half a hill glued to my feet.

This hill is artificial, landscape. It is here to protect the house from the noise of the highway.

An artificial hill on top of a natural one, the one the house sits on, settles in.

And yet, it is curious that in building the house the roles of the hills get reversed. The natural elevation has become human settlement, civilized and cultivated, while the hill placed by the architect seems part of the natural environment. The artificial mound meets the aluminum floor of the living room. As in the Robin Hood Gardens of the Smithsons, the picturesque character of the mound contrasts and reinforces the geometric reason of the architecture.

Is this house a patio or a pavilion? From the ground floor, as you enter, it is a patio house...

Yeah. A binuclear, almost like the ones Breuer proposed in the 1950s... But here, from the top of the hill it is a pavilion in the landscape, like the Farnsworth House or the Eames House.

The Eames House is both patio and pavilion. Alison Smithson said this somewhere...

But here there is not just one patio? There are two. Well, it is actually three. Even four, if we consider the void of the elevator. Three patios separate four houses. One for the couple, one for the children, one for the guests, and one for the custodians.

A patio house which is really many houses and many patios.

This spongy microworld is a reflection of the complex articulations of human lives, their accidents and their bonds.

Hmmmm.

All the patios separate. Only one patio, the void of the elevator, connects, mending the shattered world of its inhabitants.

Have you noticed that they are all in their own worlds?

Yes, they are all like the house.

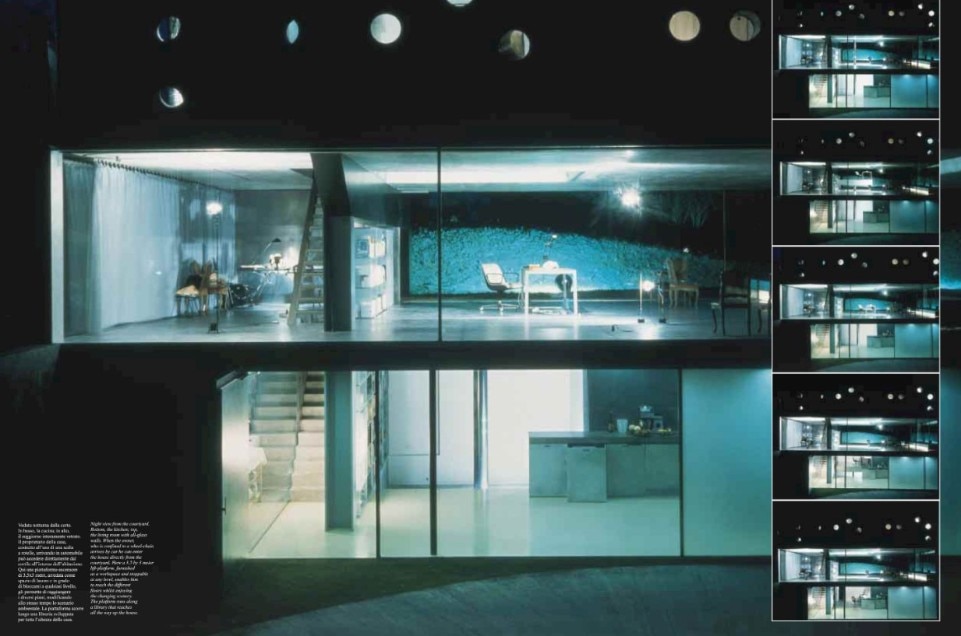

The woman is in the lower house. The young kid is across the patio in the caretakers, house – I can hear her practicing piano. The oldest one is talking with a pal in the outside glass house. The man is in the glass house, with the visitors. Now and then, one of them wanders into the living room, as if to check that everything is still there, and then leaves again... as when the youngest child circled the room asking, from a distance, if Rem spoke Spanish, too, then left.

Or when the woman brought up the coffee and the cake, then left. The house allows everyone to disappear into their worlds. It is as if the cell of Le Corbusier had been made available to all. The structure is quite striking...

...and showy, almost exhibitionist. It seems quite complex. But, in fact, everything is held by two portals and a beam, as if it were a bridge. The structure, as everything in the house, expresses in a complex form, very simple ideas. If you compare this bridge house to the glass house on the hillside of Mies or the bridge house version of the Eames House...

Yes. But the program in those houses is much simpler, really minimal. We are in a completely different world here. In fact, we are in many worlds, many intersecting worlds.

Instead of braced transparency, as with Mies or the Eames, the beambridge here is a perforated box of concrete, rigid and hermetic – the house of dreams that rests on one portal and hangs from the other one.

The structure enters and leaves the house. It is sometimes inside, sometimes outside. It is as if it wanted to extend itself beyond the space...

In each of the long facades, only one of the portals advances while the other one tends to disappear, withdrawing into the interior. This gives the house an air of impossibility, of mysterious instability.

It is the art of the conjurer. He draws your attention with one hand, and with the other one, the one you are not looking at, he does the trick. From the entrance patio, the house seems to hang from a thread. It is so striking the presence of this tense cable, detached from the facade by more than two meters. It is as if the house would come crashing down if one were to cut it.

Or float up like a balloon. No longer secured by its string, the concrete box might just fly away.

The cable appears even thinner when we look at it from the patio of the glass house, against the fat columnstaircase covered with stainless steel, almost a mirror, that completes the portico. They are like Laurel and Hardy. It calls to mind the grotesque images of halls of mirrors in amusement parks.

They were there, amused, watching themselves, alternatively fat and deformed or elongated as Greco figures, when the woman came to ask whether they wanted to see inside. The children and a friend were now playing cards, sitting on the floor of the patio of the glass house. From there they could see that below, at a prudent distance from the house, in the same place where they themselves had parked, there were now several cars and people looking up in the direction of the house as if it were a recently landed spacecraft. It was quite common, the children said. Sunday afternoon entertainment.

The house was full of boxes lying around as if the inhabitants had just moved in. They had been there since September. It didn’t seem to bother them in the slightest. On the contrary, it was as if it suited them that way. The house was beautiful in that state of déshabillé, like the occupants, so attractive without even trying. They thought the house should be photographed like that, with all the boxes, the wrapped paintings on the floor against the walls, mud inside and out, loose cables, unpainted walls, old furniture and new furniture, antiques, all still without a position – everything in process, half way, in the middle, under construction, half-dressed.

The woman showed the house as if it were a contemporary work of art. This shouldn’t be a surprise. Such houses are commissioned to be works of art. But there was something remarkable about her relationship to the work, more like that of a curator, speaking precisely about the work, about every detail, every decision.

She was reminded of Peter Seller’s words upon entering an elevator for the first time in Being There: ‘How long do we have to wait in this little room?’

What color will the walls of the patio be on the inside?

The one with the entrance will be sand color like the color of the stone on the outside, the other will be grey, and the one in the back, almost black.

“Almost black”? The choice of words speaks of a certain complicity between the client and the architect, of a shared sensibility capable of arriving at the last shade of the work.

The intimacy of a partnership, a collaboration.

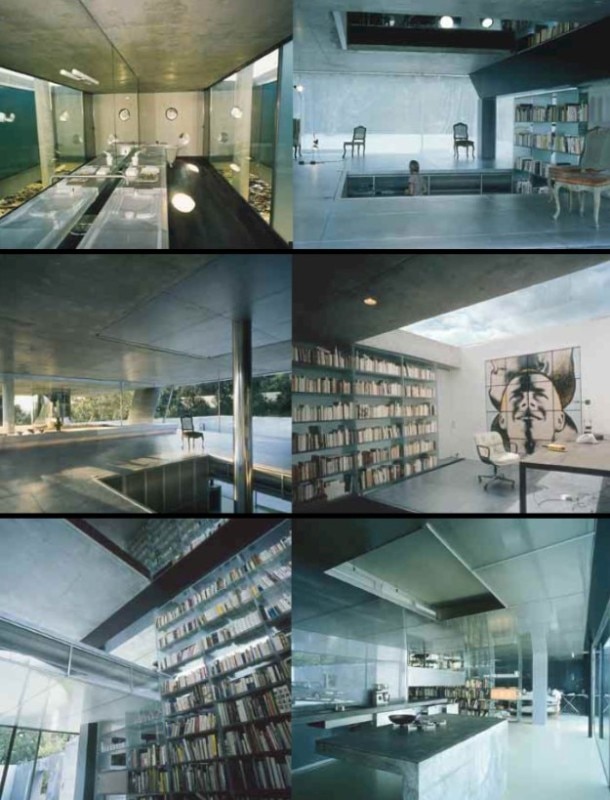

The entrance is a surprise. A sliding glass door, in the narrowest point of the plan, and opening directly onto the stove...

There are two entry doors, in aluminum, in the extremes of the facade: the children’s entrance and the service entrance.

One has the sensation of walking right into the heart of the house. Upon entering, the first thing you see is the shaft of the elevator and the piston.

You enter and you are already there. No intermediate space. No need for it. It is also the logic of the wheelchair. You go from the car to the elevator on wheels. It is a mechanized promenade.

The house has been thought to facilitate everyday life for my husband. The patio is the first room in the house, the entrance to the house is the entrance to the patio. The kitchen, under construction, exposed the trusses of a ceiling not yet in place. A gigantic Aaltian vase held a dazzling bunch of gladiolus. The ceiling of the kitchen was supposed to have been of aluminum plates, like the floor of the living room and like the floor of the platform-elevator.

With the same material for roof and floor you get continuity in section, a free section as Moneo would put it.

But, in the end, the perforated aluminum plates will be replaced with plates of polycarbonate. We ran out of money. Several samples of this material, of considerable size with different textures and thickness, lay around, inside and outside the house. If the free plan liberated the walls from their loadbearing function, the free section liberates the ground. Floors float. The elevator is no longer an enclosed space, a sensory deprivation chamber, where, as Johnson once put it, “all architecture stops.” (She was reminded of Peter Seller’s words upon entering an elevator for the first time in Being There: “How long do we have to wait in this little room?”) The platform-elevator, 3x3.5 meters (almost the 3.5-by-3.5-meter dimensions of Le Corbusier’s Cabanon in Cap Martin), is a room that contains everything the husband needs. It is his house. This room moves up and down, can stop on all levels and anywhere in between. As Rem had put it, “The movement of the elevator changed each time the architecture of the house. A machine was its heart.” The elevator is the most cinematographic space in the house and the most architectural. It dictates a sectional journey through the heart of the house. The elevator returns to its exhilarating beginnings. Giedion wrote about the spatial experience of moving through the Eiffel Tower: “The interpenetration of continuously changing viewpoints creates, in the eye of the spectator, a glimpse into four-dimensional experience.” Old apartment houses in Spain – like those in which she and Blanca had grown up – still have glass elevators furnished with upholstered benches, decorated lamps, and mirrors, like a small waiting room, running through the core of the building, ceilings becoming floors, passing by the viewer as in a suspense movie. And in New York, she once lived on the top floor of a loft building that had a huge manually operated industrial elevator running along the facade with a big horizontal window. As she rode the elevator, she could peak between the floors into the lofts of the building across the street – the details of their life exposed from different angles as she moved up. It was a movie. OMA’s technique of design is cinematic montage. As with the houses of Le Corbusier or Mies, more important than the object is how it frames the landscape in which it sits, how it creates that landscape. Even Mies’s Kröller-Müller House is first of all a landscape. Perhaps the most important thing that OMA is saying is that there are no more objects. Landscape is everything. The role of architecture to point to it, to produce it. In the ground floor of the house the spaces are like caves excavated from the hill.

And this staircase? Seems like an homage to Gaudì.

Or Kiesler.

Yes. The starting point is as amorphous and enveloping. And as you go up, it becomes a cave open to the exterior.

The walls of the cave were wet. After the heavy rain, water had come in through the steps and the walls. A couple of days before Rem had been there to see it.

Why will it be that all the big-name architects – Le Corbusier, Mies, Frank Lloyd Wright – have leaks?

They told the woman a few stories of water in modern architecture. How Madame Savoye had called in Le Corbusier in the middle of the night to her flooded villa and how, without lifting his eyes from the sight, he had asked for a piece of paper, rejected the pencil that was offered, and very deliberately made a boat with the paper and put it on the water, saying something about how beautiful the house looked that way. And how Frank Lloyd Wright, called by an exasperated client because a drip was falling on his chair in the middle of a dinner party, had advised the client to move the chair. They were not sure she appreciated the stories. Water always touches a nerve. Some workers were trying, for the first time, the movement of the platform-elevator with a huge remote control like the ones on an industrial crane. The children and a friend enjoyed the novelty, checking the operations of the remote with the expertise of the push-button generation. Spoke with one and the other as she directed the mise-en-scène of this singular domestic stage. The great three-story wall that will be accessible from the platform and hold books, artwork, and wine was not there yet. They went up the stairs and entered the glass house. It is totally transparent. Half air, half glass. Void and solid melt. Interior and exterior no longer are opposed. The membrane of enclosure and the structure disappear, dematerialize. On the outside of the glass house, looking at the perfectly smooth ceiling, they discovered a precise cartography of fine lines that run in parallel, separate, or form a helicoidal figure around the spiral staircase. Those are the electrified guides along which the canvases of our collection will move from the inside to the outside.

It seems like a very festive thing to do, to get the canvases out.

Like hanging the linens. A new development of the architecture of the curtain, of the mask, that can be seen in so many of OMA’s projects. A massive double glazed motorized sliding door, eight and a half meters long, travels eleven meters along the north side of the glass house. The framing is concealed within the floor and ceiling to produce a sense of complete transparency. Was it an echo of the Tugendhat House, where a huge window sinks into the basement with the help of a motor? At ground level, a flush surface provides unrestricted wheelchair access to the outside. It is as if the wheelchair erases the line between inside and outside, when it erases the distinction between machine and house. The ambiguity between inside and outside is a constant play. When the big window is open and the canvases hang outside, the outside room will become an inside and, vice versa, the interior will be the natural extension of the hill. To go from there to the children’s rooms one has to take the spiral staircase. In the middle of all this fluidity and efficiency, access is suddenly restricted. The wheelchair cannot enter the most private territory of the children without help. The four-sided children’s house has been divided in three, and each room is different. The dynamism of the plan is a whirlwind originating in the spiral. This accelerated centrifugal movement contrasts with the centered stability of the neighboring house where the parents live. The play between static and dynamic is also reflected in the different character of the portal frames. In all the rooms, each wall is different: one is grey, another is wood, and the third one seems to be graffiti. The grey wall becomes darker in each subsequent room.

The ideal client of modern architecture, the culmination of a century of research, is a wheelchair-bound body, mechanized in its movements, fully connected to cyberspace. The free section extends seamlessly into the Internet.

The closet is just a slit of natural light in the roof and a bar to hang the clothes. The play of colors of the clothes of the middle child – purple, fuchsia, pistachio, violet, yellow, orange – makes of this noncloset an art work. The small, round windows, cut through the thick walls at different heights and angles to focus on limited views, give the rooms an air of rest.

Rem wanted the upper house to be very closed, and under it, the living room to be very open to the natural environment. Each window has been thought according to the height of who sleeps in that room and according to where they are looking from: from the bed, from the work table, from the shower... They also take into account the movements in the room and what surrounds the house: Bordeaux, the hill, the entrance patio, a tree...

I keep thinking about Ronchamp or the studio-house of Melnikov... There is a building in La Guardia airport, a round tower of concave walls pierced with round windows...

These holes seem to be made a posteriori, excavated from the concrete wall. But it is not so. To make the formwork, they already needed a very precise calculation of the where and how of each one of them.

There is certainly nothing casual about the placement of these holes. I have seen drawings tracing the lines of sight of users of different heights (children, adults) lying down, sitting, and standing. The single universal eye of Le Corbusier’s standing men at one meter seventy five centimeters from the ground has been replaced by a multiplicity of eyes. Children’s eyes, chairbound eyes, etc.

There are three types of holes. The first type, at eye level, provides glimpses of the horizon. (The floating concrete box an ocean liner whose portholes frame a horizon – wasn’t there something about the portholes in an ocean liner framing a horizon to prevent sea sickness?) The second type frames views of the surrounding landscape, pictures, with a similar status to those hanging on walls. And, according to OMA, the third type, are “anticlaustrophobic holes framing the nearest piece of the ground.” If the fenêtre-en-longueur separated middle ground from foreground and background, eliminating the sense of perspectival depth of the porte-fenêtre, the Swiss cheese windows in Floirac separate background, middle ground, and foreground, presenting them as isolated fragments, as if there had been an explosion. Here are multiple eyes, multiple identities, children, women, invalids.

Since the children are still growing, or at least two of them, they will feel the room in constant change until they stop growing. Their height will change what they see through the windows. The smallest child will be like Alice in Wonderland. The window will be lower every day and in a few years she will have to crouch to look outside. On the other hand, she will only be able to look out from other windows when years have passed. As she grows, she will have a new vision.

I don’t remember the big pivoting circular window in the room of the middle child in the drawings.

How did they get the beds and the rest of the furniture up here? Through the spiral staircase? Or is this the reason for this window?

What wood is this? It smells of cedar.

It is a very common, industrial wood. Rem is interested in solving with great-quality materials the essential parts: the structure, the carpentry, the enclosures, but the cladding materials are very normal.

Simple materials, incredibly good finishes... I am not talking about details but about the last layer of skin. Not the joints but the surface. There are no details, that’s the point. The joints are hardly there.

And the floor, also grey. It seems very well done. What is it, linoleum? It extends seamlessly across the whole plan, even to the shower.

It is made with a mortar of polished resins. No seams, no details, no distractions... all you see is the continuity of the ground. It was dark when they left. The visitors had already gone. And the man was working at a desk in the space designed to be the woman’s study. Facing the hill through the glass wall and the screen of his computer, connected through the Internet, the telephone, the fax... he was the very figure of contemporary life. In electronic space all bodies move with the same freedom. Looking up from there into his bedroom, they saw for the first time the exercise equipment, which was probably part of his rehabilitation program. They had not been in the couple’s rooms. But from there it looked like everybody’s bedroom, crammed with exercise equipment. The gym-houses of the twenties and thirties came to mind. But also Manhattan apartments. And suddenly they realized what was so compelling about the house. The condition of the husband was an extreme case of the contemporary body. An army of chiropractors, physiotherapists, acupuncturists, laser surgeons, orthopedists, masseurs, and a million contraptions – special chairs, pillows, mattresses, back stretchers – had been developed to treat the back. As a chiropractor once told her when she was in pain: “It is a miracle that we walk. We were not designed to do that.” The ideal client of modern architecture, the culmination of a century of research, is a wheelchair-bound body, mechanized in its movements, fully connected to cyberspace. The free section extends seamlessly into the Internet.

“This house,” he told them as they were leaving, “has been my liberation.”