The History of Design he wrote in 1985, as well as the study he dedicated to the Italian scene 22 years later, have become cornerstones in the education of anyone approaching the world of design, and the same applies to his Signs of architecture (Segni), which, in addition to being one of his most famous works, also appeared on 1980s Domus in episodes dedicated to Bernini or Palladio. An artist with the Movimento Arte Concreta, a collaborator of Zanuso and then Rogers, a full professor at Università di Napoli Federico II, Renato De Fusco has made a critical approach to history the heart of a long career, also rewarded for its relevance with a Compasso d'Oro in 2008.

On issue 821 of Domus, the last of 1999, he dedicated a deep focus to our magazine as a powerful mirror through which to look at the evolution of culture in art, architecture and design, through turning points and key figures such as Gio Ponti, Edoardo Persico, Alessandro Mendini, Lisa Ponti and the editors and authors who navigated the project throughout a century.

Domus: facts and interpretation

A text on the subject of the “founder of Italian architectural and design journals”, as Domus has been called, could, as I see it, be drafted in two ways. The first on the basis of free associations, memories and a memorizable chronology, so as to get a good general picture of the connection between the Milan publication and its time, especially the fifty years, which remain paramount – of Gio Ponti’s editorship; and the second, by putting down a number of historiographic points of reference, against which to consider facts and ideas illustrated in the magazine, not only in the 1930s, but up till the present.

It is well-known moreover that historiography is approached from today’s angle, and that this has been described as transversal, in other words aimed not so much to illustrate the ‘facts’ as to talk about ideas, to put forward interpretations. Let it be added to this introductory note that Domus and this writer belong almost to the same age group. My interpretation is thus also a witnessed chronicle. In choosing the first of these two courses, I would be obliged to remember that, in general, Domus has stood, within this last century of Italian life, among the most consolidated institutions, and to follow with a list of these – from Fiat to the Corriere della Sera, from the Milan Triennale to the Venice Biennale, and from the design boom – to mention the first that come to mind – plus a large measure of ‘Milaneseness’. And if the periodical may not have enjoyed the same popularity as those institutions, it has certainly not lacked the intention and the potential to do so. A strictly Italian achievement, therefore, Domus has kept abreast of the vicissitudes of three quarters of the twentieth century in all its aspects.

This contextualization would, however, be generic. It is true that a true historical context is the compound of heterogeneous facts contemporary to the event to be studied, but only if strictly pertinent to that event – which is not the case as regards all the items on the above list. I have therefore chosen the second course. This makes the present article not actually a history of Domus, which is to some extent widely known and in other respects still very much to be surveyed in some other place, but rather, a series of reflections that are largely of a historical and methodological kind, concerning the magazine’s activity in more than three quarters of the century now ending. And by activity I mean the ‘facts’ as a whole, whilst by interpretation I mean comment on them. If I were to write a true historical account, the terms of this comparison would be: history and historiography.But the reasons for which I do not propose a historical account are different.

The history of all things can be traced. But in the case of a magazine, especially one open to so many interests as Domus is, its history is merged and confused with the ‘facts’ which, by its institution, it has recorded as they happened in the passing of time. We are talking, therefore, not about history recorded, as it were, ‘live’, but about another history ‘recorded’, ‘documented’, ‘transcribed’, and so forth. Hence the prevalent confusion between the story of the magazine proper and that of the event-works illustrated in it. What, in fact, are the ‘facts’ pertinent to Domus: those relating to the meeting between the architect Gio Ponti and the publisher Gianni Mazzocchi, who in 1928 founded the magazine? the brief interval from 1941 to ‘47 in Ponti’s editorship, filled first by Massimo Bontempelli, Giuseppe Pagano and Melchiorre Bega, then by Guglielmo Ulrich, and after the war by Ernesto N. Rogers? The suspension of publication in 1945? Ponti’s return from 1948 to ‘78, one year before his death? The succession of various editors from Casati to Mendini, from Lisa Ponti to Bellini, from Magnago Lampugnani to Burkhardt, with their various different programmes? Do ‘facts’ consist of the dealings which the magazine has established over the years with institutions, industry and its readers, or should ‘facts’ be considered rather as the works of architecture, art and design differently illustrated according to the alternation of sub-editors, graphic designers and photographers?

Certainly, all this does represent the history of Domus. But in this case its commentary, and its historiography, can only be summary, unless they were to be spread across several different histories, for which there would not be room in the present article. There is therefore a need to concentrate on ‘facts’ of one type – unless these may be seen to fit a single kind of historiographic comment. It might be supposed that the most tangible, communicable and constant kind of ‘facts’ is precisely that of the body of works illustrated by the magazine over the years: works that have their own chronology and which also mark the chronological tastes of their representation. One need only glance at the advertising pages, sometimes not all that dissimilar to those covering the actual works. The latter are what remains the most unvarying in every type of Domus story, be it an article, a book, or a theatrical performance, such as the one recently mounted under the production of Robert Wilson. However those works documented are the same as the ones to be found in other trade journals too. So in what respect is their representation distinguished in the pages of Domus?

Remembering the basic historiographic principle whereby history does not occur without a historiography which recounts and passes it down, and at the same time whereby no historiography can arise without its object, we find that ‘facts’ and interpretations should be distinct but not separate. Instead – and herein lies my greater emphasis on Domus than on other periodicals of its kind – we find paradoxically indistinctness and separateness. In fact, whilst for other types of publication, such as history books and monographic studies of a given architect, a tendency, a city, events and comment are clearly distinguishable, in the case of a magazine they present themselves in a much more confused and problematical way. Meanwhile let us underline, since it has always been its paramount characteristic, the fact that Domus deals with architecture, furniture, artisan and industrial design, the figurative arts and often many other things too that have a bearing upon visual communication. And it is precisely this positive eclecticism which lends complexity to the distinction between the ‘facts’ and their interpretation; to the extent where, as I said, a lack of critical sense induces their separateness – notably between images and text, ideas and words.

However, the fact that the works are the most ‘positive’ documentation of the Domus story is not borne out so much by the manner in which they have been presented, as by a historiographic main point. For, as Argan noted, the history of art “is the only one, among all special histories, which occurs in the presence of events and therefore does not have to evoke, nor to reconstruct or narrate, but only to interpret them [...] However ancient the work of art may be, it is always something happening in the present”.

This coincidence of the work with the event can induce the error of identifying history with historiography, but it is not so. Due also to the artistic historiography, and although the visual works are self-expressive since theirs is a language in its own right, they still have to be accompanied by a comment, by a coexistence of history and criticism. But another aspect of the ‘reality’ of works of art is true: their positive presence makes itself felt even if they are not actually realised but remain in the project stage.

None of the other project-programmes has the iconicity characteristic of architecture and design: the likeness between the drawing and what it illustrates. Now this property is of great importance. A bill of law, an economic programme, a politico-administrative scheme or a strategic plan, if not implemented leaves almost no trace at all or at the most can be retraced only by professional archivists. Architectural drawings on the other hand, even when they are not translated into concrete works but retain the iconicity mentioned, are a tangible simulacrum of the architecture which someone had intended to build. And as often happens, in the case of buildings left unfinished or destroyed, their projects constitute the sole evidence of an initial architectural programme or of the original state of their construction. To this link between the work and the event is added the fact that, for a journal of architecture, design and the visual arts, it is indispensable to keep up with the news. Thus the unvarying contemporaneity of the work of art even gives rise to a “history in its realisation”. It may be objected that this testifying presence contrasts with the so-called “historical perspective”. But whilst perhaps this may be true of books and monographs, it certainly does not apply to a publication which, being a periodical, cannot but follow the news. Nor can the distinction between history and news be invoked against the concept of a “history in the making”. Because the first is not based on the time lapse between facts and comment, but on their judgement, which leaves aside the date on which an event may occurred.

Having chosen the kind of history entrusted to work-events, or better, to their representation, it remains to be seen what type of comment, what interpretation, and what historiography may correspond to them. And this is the most interesting point not only about the moment in which the comment was associated with the ‘fact’ (eg as Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye was published in Domus alongside works by De Finetti, Muzio, Canino and Ponti himself), but also about the present in which we interpret that juxtaposition. Basically, though works of art remain constant in time, to the extent of suggesting a “history halted”, their comment, study and interpretation change. And they change particularly in a magazine which, as we were saying, must take into account a multiplicity of topics, current affairs, public tastes, etc. The most flagrant proof of the variability of interpretation comes precisely from the sort of publications examined here; from the way, for instance, the same work may be documented in Domus, Casabella or in Zevi’s magazine. The variability of that documentation seems to put the ‘power’ of the facts into a fresh light. It might also show that Nietzsche is right to observe that: “Against positivism, which stops at phenomena ‘there are only the facts'. I would say: no, it is precisely the facts that are not there, but only interpretations. We cannot notice any fact ‘in se’.

It is perhaps absurd to want something of the sort”. Even without necessarily sharing this judgement, the point that we have already made about facts having been separated from their interpretation can be seen to be true in part, and in any case as far as Domus is concerned. But, if we were to critically survey that separation, by what criterion can this be done? In the case in point, what might be a suitable key with which to interpret the conceptual position or, more simply, the formula adopted by Domus? What periodicity of the magazine itself? Its contextualization during fascism, postwar reconstruction, the economic ‘miracle’, and the so-called first republic, right up to the present years of magnificent European destiny and progress? A comprehensive answer might be found in Persico, who wrote in 1930: “A history of art can always be resolved in a compendium of civilised history: suffice it to put human affairs into the mirror of plastic values”.

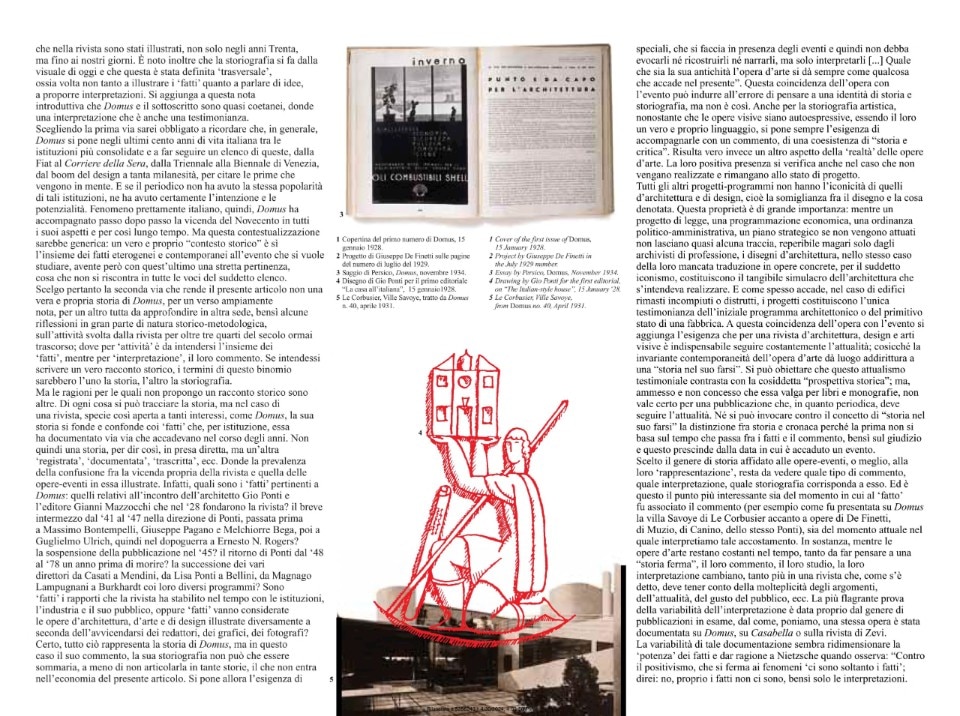

A year later however, in a judgement clearly referring to the contingent controversy, he considered it trite to claim that “the value of a work or of an art movement can be judged by referring them primarily to their social importance [...] or sometimes, even by electing the arts and letters to the rank of rulers of peoples”. We note that there is no contradiction, but only uncertainty, between the two propositions. It could be said in the meantime that the increased critical awareness of Domus’s early years affords only a starting point from which to talk about that periodical. One of Persico's many merits in fact was that he harboured doubts in a period characterised by indisputable certainties. One need only read his significant essay, “Punto e da capo per l'architettura”, published in the magazine in November 1934, to realise how different and distant was his position from that of Domus itself. On the other hand, nothing practical can be constructed on doubts. So we note that the birth of this periodical, its long life and international success, even that positively businesslike touch, stem from the decisiveness of Ponti and Mazzocchi.

The latter was also the founder of Editoriale Domus, the house that has published the magazine ever since 1928 – a rare feat for an architecture and design journal. That their programme also set out to address the middle classes as far as the art of homes was concerned, is a sign that a periodical of the kind was right on target. It is also an indication of its topical strength: the slogan that appeared during the first years of the magazine – “our advertising is the best guide to what you buy” – is matched in timely fashion by the most popular talk-show of our own day.

Only by backing decisive and pragmatic positions did Ponti succeed in characterising his magazine and fulfilling its programme, in other words – as its current editor has written – to “enhance craft quality next to that of industry, to give prominence to formal innovations and to the role of the plastic arts in architecture and design. In short, to present history from the point of view of the transformation of a slightly bourgeois and somewhat reformatory taste, though always in line with the freshest topical incidence, typical – it must be said – of a public which, still and always, wants to be kept up to date without too many shocks”. If the guidance of Persico himself does not help us to solve the problem of interpretation, it only remains for us to refer, as we have already done and stated since the beginning, to a number of main points of historiography. Or rather, to criticism of those points, many of which have proved to be commonplaces. Indeed it does not appear to be quite true that the old aphorism that history is a magistra vitae, which, related to our subject, seems not to be respected, in that many of the errors in the running of Domus were repeated despite the presumed lesson of history: and I refer, aside from a few collusions with economic and political power, to a perspective of tedious optimism, and to the occasional tumble on the plane of taste too. Nor is another mythic credence any more reliable: that of the so-called “historical truth”.

The whole vexata quaestio of the cultural politics of fascism; the clash between cultural politics and the politics of culture (meaning that of men of culture as such, as Norberto Bobbio has usefully pointed out); and the different behaviours shown towards the regime by architects, can never be brought to a unified conclusion until a general judgement has been ‘convened’. This moreover is the only reasonable way of talking about a “historical truth”. Another milestone to be connected to the setting out of ideas that fed the Domus story is that of the continuity, or non-continuity, of history. This concerns the successive editors of the publication, as much as Ernesto N. Rogers and his famous editorial for Casabella titled “Continuity or crisis?”, which marked a turning-point in the debate and in the actual production of Italian architecture after the war. And some see that alternative as a key juncture in our architectural history.

From the 1930s all Italian architects were concerned with the question of how to reconcile our national tradition with European rationalism, or at any rate with the goals of modernity, often falling into ingenuous errors. Typical among these was that of a ‘Mediterraneanness’, according to which, precisely in order to reconcile the ancient with the new, the most absurd claims were advanced. It was maintained that the pauperism of our peasant and fishermen’s houses, with their formal minimalism, would actually have provided a source of inspiration to European architects. Nor was the myth of ‘Mediterraneanness’ nourished only by the uncertain architects of Gruppo 7, for it was endorsed more or less directly by others of much greater cultural experience: Pagano, Rogers, Cosenza and, in his way, even by Le Corbusier. A few years after the Second World War, almost nobody had raised the problem of whether to reconcile and to continue our national tradition not only with rationalism, but even with modernity. Both of which were for that matter placed in doubt by the so-called postmodern condition, of which postmodernism as an architectural trend revealed itself to be only an epiphenomenon.

The problem remains however of how to check whether and to what extent the vicissitudes of contemporary architecture are or are not a continuation both of the past remote, and of the present perfect, defined as “the tradition of the new”. An answer can be found, evidently outside the disciplinary debate, in the field of historiographic theory. Starting from a different theme, by asking ourselves by what token the researcher selects the causes needed to explain a historic event, Giuseppe Galasso’s answer is “by the token of creativity, originality and innovation of every present compared to every past. Every action takes its place in the past and is its temporal continuation. But it is also a break with the past [...], a fracture in the chain of what happens. And it is this fracture that differentiates the present from the past, the unknown landing-place from the known, the choice, which is not only the selection of the alternatives in play, but is, together, the modification of those alternatives in the very act of selecting. And, with that, it is the illumination, the revelation of the ultimate sense which the alternatives in play come to assume”.

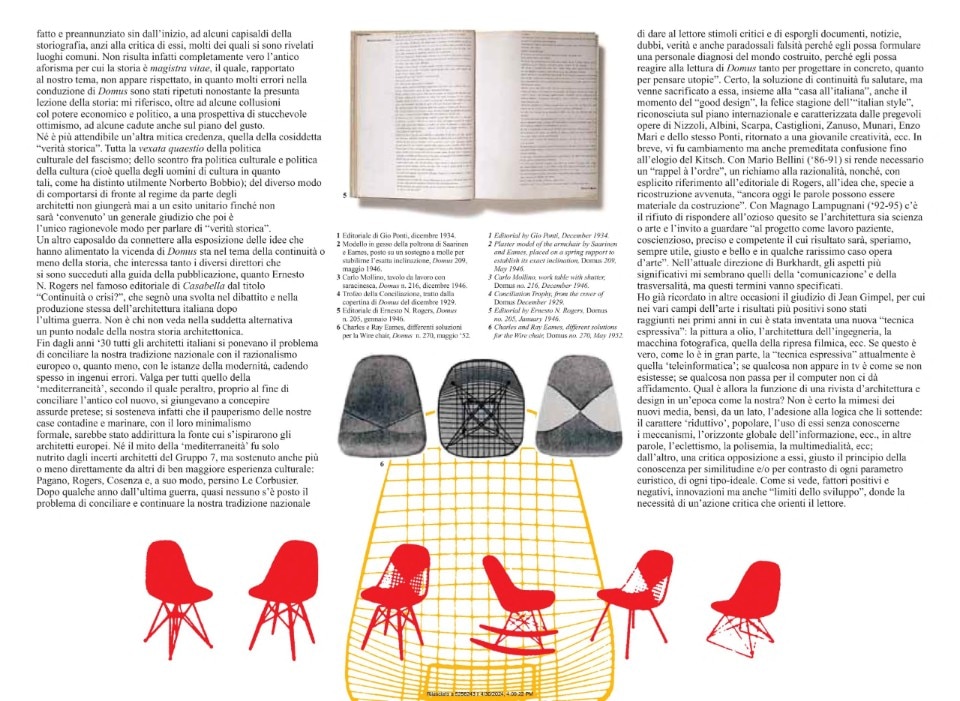

The indication is I feel, the most realistic and inclusive both of what happens in history and of what is evinced by historiography, as well as the best fitted to the ups and downs of art, inasmuch as the break is sparked by a creative act. And at this point, precisely on the basis of interruptions, we may mention the different lines pursued by the magazine in the course of time under its various editors. First of all with Ponti – who remains in any case the leading figure, as well as an artist of great talent – Domus had already dropped its initial nationalistic programme, that of “the Italian-style home”, in favour of a wider survey of international buildings and products. Under the brief editorship of Rogers (1946-48), an attempt was made to explore this policy and most of all to justify the survival of art in the face of the catastrophe of war and destruction. “We ought to rush in with a brick, a beam, a sheet of glass, and here we are instead with a magazine. To the hungry we give not bread, to the shipwrecked not a raft, but words [...] What value can beauty have to these people? [...] The contrast between art and morals becomes sensitive precisely whenever one is about to face the issue of existence on a level of more severe customs [...] The extremes of our reasoning may lead us to a utopia and to the commonplace, because if we ask too much we seek the unattainable, and if we look only at what surrounds us we are liable to be content with too little”. And the essay concludes that “the house is a question of limits (as is for that matter almost every other question of existence).

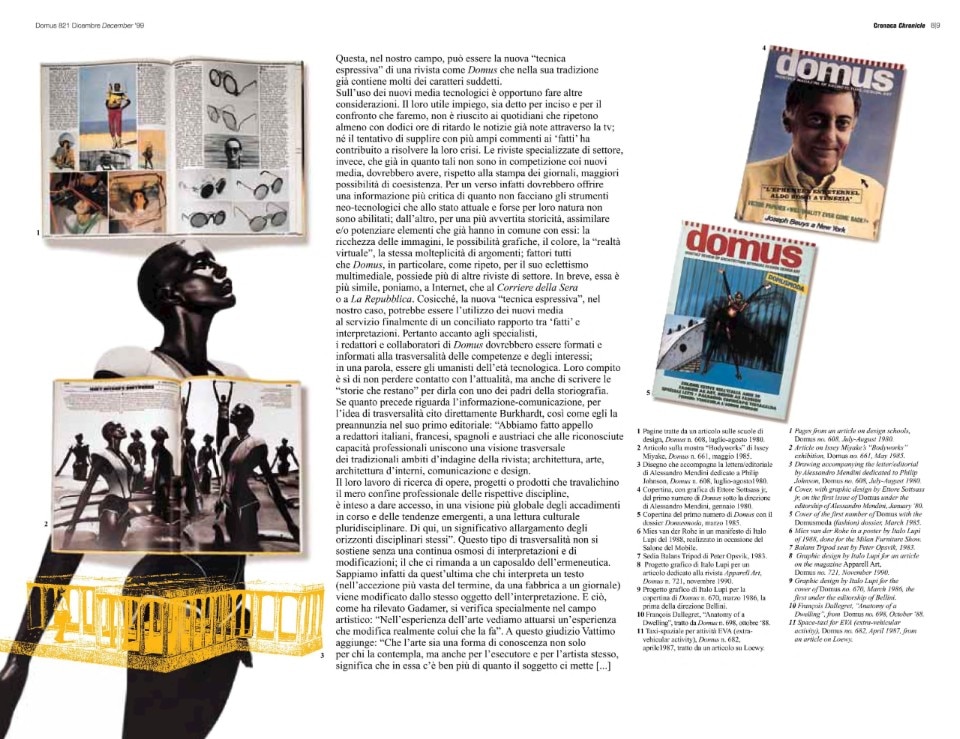

But the definition of those limits is a matter of culture, which is exactly where the house brings us back to (as indeed do the other limits of existence). If that is so, then words, too, are construction material. And even a magazine can aspire to form such material”. With Alessandro Mendini (1979-85), despite deference to Ponti and assurances of continuity, Domus took a very definite turn. In his first editorial we read: “I believe the problems of design and image should be seen today in terms of a working chaos rather than of a corporative demagogy [...] The hypothesis is provide readers with critical stimuli and to confront them with documents, news, doubts, truths and also paradoxical falsehoods, so that they can formulate their own personal diagnosis of the built world, and react to their reading of Domus as much to design in concrete terms as to contemplate utopias”.

To be sure, the interruption was salutary, but also sacrificed to it, along with the “Italian-style home”, was the phase of good design, the fruitful season of Italian style, acclaimed internationally and characterised by the distinguished works of Nizzoli, Albini, Scarpa, Castiglioni, Zanuso, Munari, Enzo Mari and Ponti himself, who had regained a youthful creativity, etc. In short, there was a change but also a premeditated confusion to the point of eulogizing Kitsch. With Mario Bellini (1986-91) a recall to order became necessary, a recall to rationality as well as – in an explicit reference to Rogers’ editorial – to the idea that, especially after postwar reconstruction, “words can even now be material for construction”. With Magnago Lampugnani (1992-95) we witnessed a refusal to respond to the idle question of whether architecture is science or art, and an invitation to look “at design as a patient, conscientious, precise and competent work whose result will, we hope, always be useful, right and beautiful and in a few very rare cases a work of art”. Under the current editorship of Burkhardt, the most significant aspects seem to me to be those of ‘communication’ and transversality, though these terms need to be specified.

I have already recalled on other occasions the judgement expressed by Jean Gimpel, whereby in the various fields of art the most positive results have been achieved in the early years in which a new “expressive technique” was invented, namely: oil painting, the architecture of engineering, the camera, the cine-camera, etc. If this is true, as it largely is, the “expressive technique” is currently that of teleinformatics. If something does not appear on television it might as well not exist; and if something does not pass through a computer we do not trust it. So what is the function of an architecture and design journal at a time like ours? Certainly not that of an imitation of the new media, but rather, on the one hand, an adhesion to their underlying logic: the ‘reductive’ popular character, their use without understanding their mechanisms, the global horizon of information, in other words, eclecticism, polysemy, multimedia, etc; and on the other, a critical opposition to them, precisely the principle of knowledge by similitude and/or by contrast of every heuristic parameter, of every ideal standard. So, as can be seen, that implies positive and negative factors, innovation, but also “limits of development”, hence the necessity for a critical action to guide the reader. In our field, this action might be the new “expressive technique” of a magazine like Domus, which in its tradition already embodies many of the characteristics mentioned here.

Concerning the use of technological media, it is advisable to make some further considerations. Their useful employment, let it be said incidentally and for the comparison which we shall be making, has not worked with the newspapers, which repeat with a delay of at least twelve hours the news already received through television. Nor has the attempt to make up for the delay with broader comments on the ‘facts’ contributed to solve their crisis. Trade journals on the other hand, which as such are already not in competition with the new media, ought, by comparison to the daily press, to have greater possibilities of coexistence. In one way in fact they ought to be able to provide more critical information than that of the neo-technological media, which in their present state and perhaps by their nature are not so equipped; and on the other, they ought by a more deeply sensed historicity, to assimilate and/or strengthen elements which they already have in common: richness of images, graphic scope, colour, “virtual reality”, even the very multiplicity of their subjects: all factors which Domus, in particular, as I repeat, due to its multimedia eclecticism, possesses more than other journals in the trade. It is, in short, more similar, say, to the Internet than to the newspapers Corriere della Sera or Repubblica.

And so the new “expressive technique” could, in our case, be the utilisation of the new media at last in the service of a reconciled relation between ‘facts’ and interpretations. Next to the specialists therefore, the editorial staff of and contributors to Domus ought to be formed and informed in the transversality of competences and interests; in a word, to be the humanists of the technological age. Their task is, it is true, not to lose contact with current affairs, but also to write the “stories that remain”, as one of the fathers of historiography put it. If the foregoing concerns information-communication, as regards the idea of transversality I shall quote Burkhardt directly, just as he announced in his first editorial: “We have called upon Italian, French, Spanish and Austrian editors to combine with their recognized professional skills a transversal vision of the traditional areas surveyed by the magazine, namely architecture, art, interior design, communication and design.

Their search for works, projects or products which cross the merely professional borders of their respective disciplines, is intended to afford access, in a more global vision of events in progress and of emerging tendencies, to a pluridisciplinary cultural appreciation. Hence a significant widening of those same disciplinary horizons”. This type of transversality cannot be borne without a continuous osmosis of interpretations and changes; which brings us back to a milestone of hermeneutics. We know in fact from the latter science that those interpreting a text (in the broadest sense of the term, from a factory to a newspaper) are modified by that same object of interpretation. And this, as Gadamer has pointed out, occurs especially in the field of art: “In the experience of art we witness an experience that really alters the person who has it”. To this judgement Vattimo adds: “That art is a form of knowledge not only for those who contemplate it, but also for the executor and for the artist himself, means that in it there is much more than the subject puts into it [...]. The representation is first of all an event in which the artist, the executor, the reader-interpreter, are not authors, but participants”.

Now this reciprocal modification between the artistic object and the interpreting subject, be it the author or the user, becomes more significant in the case of the ‘applied’ arts, which are, in my opinion, architecture itself, despite the emphasis of its etym; design, craftsmanship and visual communication, which are the ‘facts’ illustrated by Domus. And the change is all the more interesting inasmuch as in the adjective ‘applied’ lies the whole of their problematical, both artistic and aesthetic issue, and most of all the social, economic issues of experiences and expectations: not unchangeable factors, such as the so-called pure arts, but a continually changeable, designable material. And this is where another methodological principle comes in: that of history in terms of project. In conclusion to a recent study of mine on historiographic methodology, I maintained that, if not history certainly historiography is designed on a par with a building, an object of design or whatever else we may care to prefigure. In fact, all the theorists in the field are agreed that the judgement and the actual subject to be treated are the fruit of individual choices – “all history is a choice”, wrote Febvre – of interpretations, manipulations, historiographic devices, in other words operations which also figure in the process of design. Hence the legitimacy of maintaining, as I repeat, that historiography, if not history, certainly is a project.

A confirmation of what I maintain lies in the fact that the more fantastic, imaginative and inspired a work of art is, the less it will require programming, an elaborative process, a project. Historiography is a project because, unlike fiction, which develops fantasies, it makes choices, adopts contrivances, manipulates and rationalizes what are in any case ‘facts’. So what should be said of a journal that illustrates projects or realisations which are in any case in their time designed? Is it legitimate to think of a metahistoriography, a study-history of the second instance? That is why, since it is impossible to elaborate on it here, as I mentioned at the beginning, I did not wish to write a history of Domus proper. However, to go back to the idea of historiography as a project, in our field, a monograph of an architect, a book of historical synthesis, even an architectural magazine, since they can be likened to a project, present the potential capacity to correct themselves. For a project is an alteration of the existent.

That, then, is the critical task we hope will be undertaken by the editorial staff of the magazine in question, even if at the cost of revising its consolidated formula. Domus has been, is and will be the documentation of works and projects. And when it best reconciles ‘facts’ and interpretations, fabrica et ratiocinatio, an imagination of forms and contents, it will itself become a project. Not a project serving to prepare a monthly issue, however worthy a task that may be, but a more deeply involving one with the power to change those developing it as well as those using it. For it the problem is no longer so much and solely that of creating information, as that of forming, involving, changing and inducing its traditional readers, who currently “want to be kept up-to-date without too many shocks”, to more radical positions, to adventures of the mind, to more numerous and deeper critical openings, to a greater interest in an “opinion chronicle”, which is the title given not to one of its columns, but to a text which acts as the spinal cord of each one of its issues.