Be it books or buildings, it has been 50 years now that Rem Koolhaas, also with his OMA/AMO practice, has kept positioning his research on the cutting edge of contemporary architectural production. From the postmodernism theorized in Delirious New York to diagram-buildings such as the Kunsthal in Rotterdam and the Seattle Central Library, from the scalar provocations of S,M,L,XL to the redefinition of the concept of industrial heritage represented by Fondazione Prada in Milan. The mid-2000s were the time of the Casa da Musica in Porto, a monolith “that fell to earth”, right close to a classical roundabout, which would keep inspire with its shape and spatial layout a whole generation of public building projects in the years to come. Domus published it in May 2005, on issue 881.

Casa da Musica in Porto, a meteorite in contemporary architecture

We dive into the Domus archive to go back to the 2000s, when the project by OMA radically revolutionized the image and the very idea of public buildings.

View Article details

- Shumon Basar

- 30 January 2024

The building that fell to earth Shumon Basar

Endlessy

Some three hours have passed and Ellen has not run out of treasures or secrets to show us. Rem Koolhaas calls her on the mobile phone: “What? You are still giving them the tour?” Four years on from winning the Casa da Música competition in Portugal’s second city, Porto, project architect and OMA partner Ellen van Loon is relishing our stroll around the fiefdom she has helped to construct. She ends our epic, labyrinthine journey deep in the glamorous bowels of the building, where performers will make themselves up before going on stage and where the directors of the Casa da Música will be subject to “transparent” working conditions courtesy of glass partitions. I put it to van Loon that all these transparencies and free-flowing spaces of anti-panopticism deny the possibility of illicit office micro-dynamics. “Trust me, there are plenty of hidden places in this building,” she replies knowingly.

Faux-naif box

The anecdotal story of Casa da Música’s genesis in the Rotterdam-based hothouse OMA predates the building by years. The so-called “Y2K House” – originally destined for a client who didn’t want to face his family yet still have all of them live under the same roof – was predicated on a solid, obloid mass with various isolated voids carved out.

Like the millennium bug, Y2K was a dud - until, that is, OMA needed an idea for a concert hall in Porto. By scaling the house up “five times”, according to Koolhaas, and substituting the bedrooms and storage spaces with concert, chamber and experimental music rooms, the DNA of Casa da Música came to life. This alchemical tale is typical Koolhaasian: an epistemological case study where one apparent failure lays the groundwork for a successful project.

Perhaps the most important part – both real and symbolic – of OMA’s Casa da Música is the main auditorium. After whirlwind visits to the best venues in the world, Koolhaas and his team declared that “the shoe box is the best shape for a concert hall.” It is a claim that acoustic engineer Renz van Luxemburg happily corroborates. But don’t be fooled by their shocking endorsement of “the box”. They haven’t suddenly seen the pious light, renounced irregularity and decided to go straight. It is true that Casa da Música’s principal auditorium is a huge, plywood-clad box, the kind that mediocre minimalists might leer at as if it were specialist porn. Yet this box is full of holes and interruptions, not to mention the fact that the two end walls seem to be missing.

Instead of creating a closed coffin auditorium cut off from daylight, nightlight and the city outside, the Casa da Música’s principal music space is a porous entity, opening itself up to a multiplicity of realities both near and far. Most radically, the two seemingly absent walls are in fact massive solid curtains of corrugated glass, reaching five metres high in a single stretch. The corrugation is van Luxemburg’s solution to using glass as an acoustic material. The corrugated ripples deflect sound in various ways, ameliorating the brittle hardness of glass. Despite obvious refractions, the views through the glass curtains are remarkably clear, as I can see the verdant trees in the Rotunda da Boavista across the hall. Allowing sunshine in a music auditorium is such a simple yet transgressive gesture. Gone is the feeling of perpetual nocturne we have become accustomed to. It’s like having the curtains drawn back after hundreds of years of sitting solemnly in the dark.

However, the porosity is not limited to the two end walls. Staring up at the sheer, plywood walls, I see more cut-outs in corrugated glass. Van Loon points at them and enumerates that “this is the Cyber Music Room, that’s the VIP room, and that is where the parents can leave their kids when they want to see a concert.” Everything in the building seems – in one way or another – to gravitate around this restive event space. Not content with simply being able to see the outside from inside, the main auditorium is also a two-way entertainment panopticon. It is a space from which one can look out at everything and into which one can look from any place. I can imagine traditionalists decrying such visual play as “profane pollution”. OMA are providing simultaneous, screen-in-screen viewing compared to the single channel, single image TV of the past. But are they just lazily succumbing to the cliché that our attention spans are measured in seconds these days? That we don’t actually watch TV but surf an excess of channels, listlessly and distractedly? I don’t think so. There is nothing cynical about the desire to maximise relationships within the building and turn them into, if you will, a chorus of voices rather than one big fat soloist hogging the stage. After all, we listen with our eyes; we take in images when we hear Mozart’s music. Madonna, for one, has been exploiting this for decades. To deny this is to deny how we make sense of sonic matter.

The walls of the auditorium are decorated in a highly pixilated rendition of plywood grain blown up fifty times and painstakingly applied in five-centimetre squared gold leaf sheets. The only people skilled enough to apply this were restoration specialists with obviously superhuman levels of patience. Perhaps the same voluntary victims knitted Petra Blaise’s stunning hand-knitted semi-blackout curtain. Its knots are the size of a small girl’s head, meticulously woven around nylon netting. Were corrupted computer files sent to the gold-leafers and curtain knitters, eliciting an erroneously scaled decorative scheme compared to the actual architecture? A Baroque Iberian organ is being set up at both ends of the stage. However, it’s fake, a carcass, a prop. One day, when enough money is raised, they’ll buy the piece that actually produces music. Until then, van Luxemburg tells me, its ornate gilt detailing provides critical acoustics.

Touchy

From the diurnally lit auditorium foyer, we move through circulation tunnels clad in aluminium panels and white concrete. This palette is uncharacteristically calm for an OMA building, though I am reminded of their recent Dutch Embassy project in Berlin. There, a muted layer of aluminium floor/wall/ceiling was counterpointed with acidic colour. At Casa da Música, however, the contrast between transit space and “event rooms” is exaggerated much further.

Portugal is well known for its wines and tripe, not to mention its ceramics. In Casa da Música’s VIP room, scenes of 18th-century court life have been handpainted in blue onto tiles. In the Renaissance room, adjacent to the main auditorium, an M.C. Escher optical effect is created through glazed, accented tiles that envelop the space like expensive wrapping paper. On the roof that houses the restaurant, a chunk of the building is carved away, leaving a checkerboard lining of tiles. Even the handle on the fire door is given the same finish. One would never have predicted that OMA, once infamous for its love affair with semi-debased, off-the-shelf building materials, would embrace the handmade as emphatically as they have here. It borders on quasi-contextual hysteria, with a touch of sentimentality thrown in for good measure.

Heavenly accident

As we loop through, under, beside and over the main auditorium, I find it impossible to picture the plan of the building. Indeed, it is a composition that could only have been conceived as a three-dimensional thing, since almost no space repeats and floor levels see-saw from room to room. The relentless inventiveness makes one giddy, and the more one moves around, the more exquisite the organisation appears. Here, nothing is exaggerated as everything remains dutifully functional. The north side is densely layered with technical spaces, whereas the south side is completely empty. It’s here that the soaring concrete atrium dazzles. The white concrete is structural and has been poured at unprecedented oblique angles.

Its resulting effect is to give the building intelligible solidity and therefore an otherworldly coherence. During construction at least three interstitial spaces, un-anticipated during the modelling stages, revealed themselves. The most spectacular of these is found above the main auditorium, where terraced white floors lead to a huge retractable roof. It is the one space where acoustics have not been calculated, lending it an echoic quality that I imagine heaven will possess.

Amateur vs Stradivarius?

The temptation to call the Casa da Música an “instrument” is too great to refuse. OMA’s dogged research into new forms of architectural typology, practiced since the 1970s, is beginning to finally see results. Seattle Public Library fused the monumental with the civic under the aegis of a sublime atrium. The Dutch Embassy conjured up twenty-four levels from just eleven floors, shuffling the tower block type into something well beyond slab predictability. With the Casa da Música, OMA has presented Porto with a new musical benchmark – the sequel to Stradivarius or Steinway. The problem is that if I were to take either of those venerated instruments and attempt to play them, only cacophonous un-listenable noise would emanate. Euphony is generated as much from the player as from the instrument.

I put this question to Pedro Burmester, a noted concert pianist who has been the driving force behind the Casa da Música vision. “How do you grab the building as a whole?” he bluntly asks. “The challenge here is to see everything that works inside as being connected to something else, like the building is. You are in one place and you see another place: this should be the same thought as you organise the programming of the building. You have to use the whole building as an instrument.” It is a complex and demanding challenge, one that demands direction akin to a conductor who must urgently oversee an orchestra. Burmester puts it best when he says: “Every corner has a different atmosphere…it’s impossible to use Casa da Música normally.”

Labyrinthine question

So far, I have been inside the Casa da Música for two hundred and twelve minutes and it doesn’t require much imagination to believe that there is potentially another thousand minutes of Piranesian complexity. If the mythical Ariadne had tried to spin her cunning thread to trace a way out of Casa da Música’s labyrinths, she would probably have given up in a fit of exasperation. After all, this is no ordinary labyrinth, but one in the particular form of a monumental question marooned in Porto. I think it was Godard who once said that it isn’t answers that really matter but rather formulating the right question. Questions open up horizons of what is possible, what is thinkable and what is achievable. Questions demarcate the boundaries of what makes up our reality. Not all questions need to be answered – but I suspect that the question Casa da Música asks of its administration, its governing politicians and its audience must be answered in some engaged and directed way. Otherwise it will remain as a polished white gravestone to the failure of cultural renewal. Accordingly, Burmester’s ultimate ambition is to rouse Porto’s local inhabitants through the stimulating presence of OMA’s alien visitor. He adds: “You have to conquer proximity first, the rest will follow.”

Object object

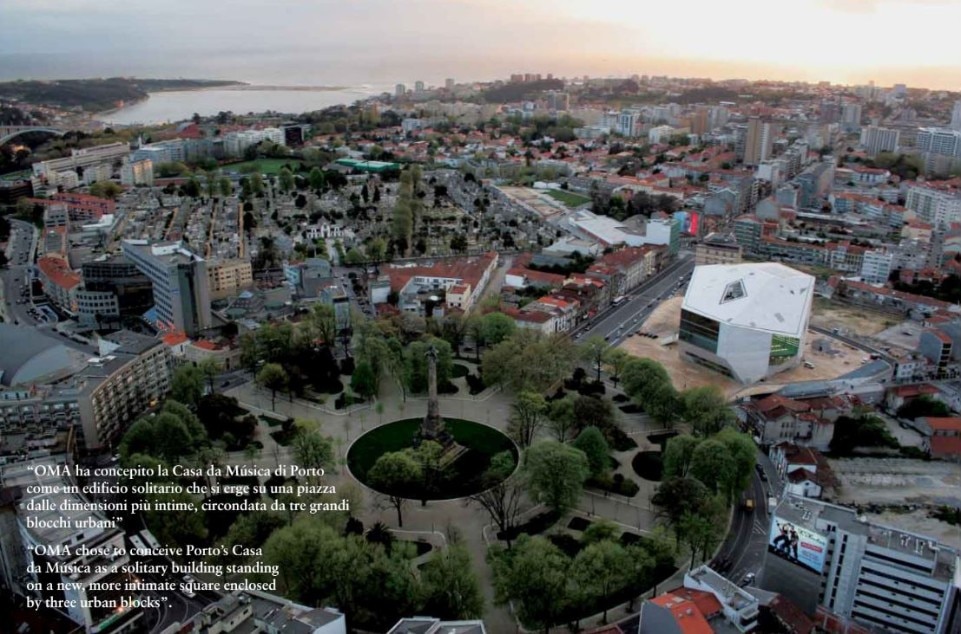

The day before I arrive, members of OMA hire a helicopter to shoot the building from the sky. Floating above, you see Porto’s heterogeneous urbanity that begins at the sea and pushes through the medieval district into the faded semidecay around the Casa da Música. A cemetery, low level houses and a drizzle of shops and derelict buildings provide an earthy, unpolished city grain. Against this backdrop, the Casa da Música leaps out both in terms of its exceptional scale and its clunky, unadorned envelope shape. A reddish travertine plaza, pinched upwards at its ends like a disobedient rug, provides the white alien with a vibrant playground.

Looking at the building from above begs another question: has OMA just built an early, unfinished model? Its white angularity and epically straightforward cut-outs make it look just like one of the hundreds of attempts produced during the design process. From high up, the corrugated glass looks like corrugated plastic sheeting so beloved by architectural model-makers. The travertine is just copy-pasted textures pieced together from ink-jet prints and PVA glue.

More perplexing still is that at ground level, as one walks around it, the structure doesn’t jut out improperly or brutishly. Instead, like David Bowie’s The Man Who Fell to Earth, the Casa’s alien landing has irrationally assimilated to its new context with little effort. Whichever angle you approach it from, you see one of its faces mingling with the existing views. From the Rotunda da Boavista, it looks picturesque. From the cemetery behind it, one imagines reverent funerary architecture. From the nearby homes, it appears domestic. This alien doesn’t want to “go home” like E.T. did at the end of Spielberg’s extra-terrestrial fairytale. The Casa appears to have found a home amidst the surrounding ambience of decline not by simulating it, but by being the exact opposite.

Irony-free sublime

Upon leaving the Casa da Música bewildered and bedazzled, my final hunch is that beyond its status as typological experiment, curatorial challenge and cultural cocktail shaker, this project is an affirmation of architecture as architecture. It isn’t OMA building the afterbirth of some profound research they got bored of and it isn’t OMA constructing an index to late-modernity’s abject crapness. There is no envious lover, no “fuck context”, no ironic repose and no ¥¤$. It is OMA indulging in architecture’s inimitable self without losing the irascible trait of doing the wrong things in the right places. I’d say that Koolhaas, van Loon and their prodigiously talented team of architects, furniture designers, engineers and local craftspeople are conjuring up a new kind of contemporary sublime. They’d just never admit it.

Ellen reassures me that the next time I come back, she’ll show me the rest of the Casa da Música. And then I’ll be done.