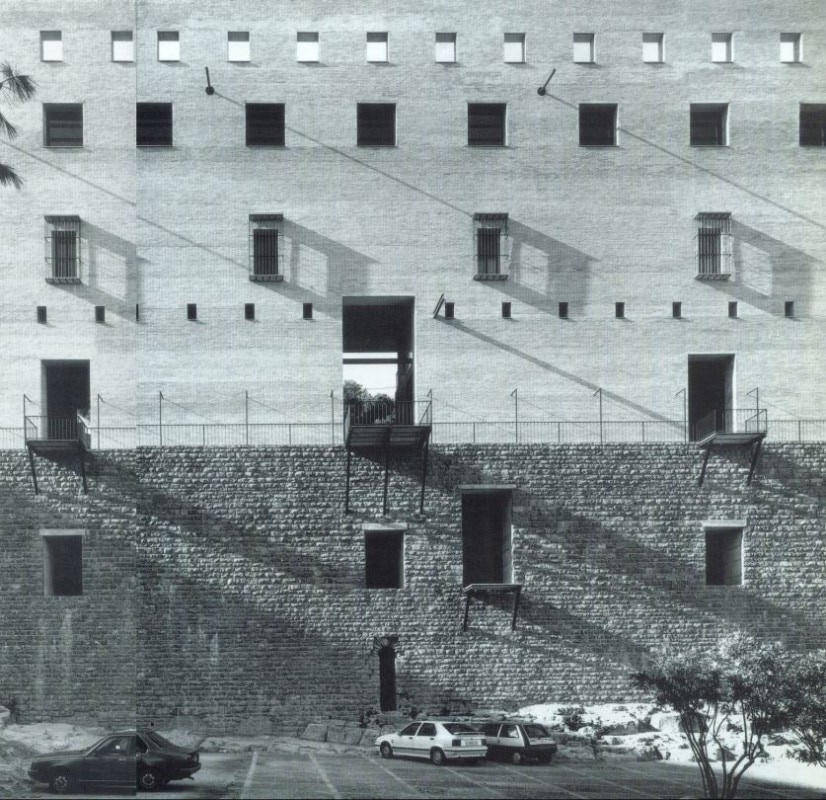

“Although he has refrained from claiming any kind of monopoly on virtue, he has nonetheless continued to point to certain austere models as the embodiment of a critical silent modus appropriate to a destitute age”, wrote Kenneth Frampton in January 1994, in an essay for Domus issue 756. He was talking about Giorgio Grassi, and in the immediately preceding pages images and drawings flowed of the most recent work by the Milanese architect, one of Rogers’ disciples in the Casabella-Continuità incubator along with Aulenti, Rossi, De Carlo and many others: the renovation, as the article titles, of the Roman theater in the Spanish city of Sagunto.

“The antique ground has been both respected and violated at the same time”, putting the theater back into service through its functional completion and the assumption of the rational matrix of its original structures. “In doing this he has by-passed, so to speak, the potential for creating one more touristic ruin, that is so often the facile result of what passes today to archaeological restoration”, Frampton says again, of a work destined to become the subject of lengthy discussions, broadly embracing the very notion of restoration. “Grassi’s insistence that the ethical task of architecture today is always to express the contradictions out of which it arises finds its most poignant expression here in the thick wall of the permanent set”.

The Roman Theatre at Sagunto Restructured

The hypothesis here outlined envisages, where necessary, reinforcement of existing structures, or their liberation, and the partial completion of outstanding ancient wall structures, with a view to making the complex of buildings that make up the Roman theatre more comprehensible. This would involve making it easier to distinguish its different parts, the relations between them, their hierarchies, individual roles etc., and lastly the way in which they come together to define an articulate and complicated architectural form, but one that is still absolutely unitary. This is in fact the type of the Roman theatre over the brief history of its construction and throughout its long and constant influence on the history of architectural forms.

Also envisaged is the reconstruction of those essential parts of the theatre’s structure that are necessary to convey a clear idea of the architectural space of the Roman theatre of Sagunto in its entirety. Yet this will be done with respect for the archaeological remains, indeed on the basis of the present ruins, including the modest historical overlays (in this case: the completions, even the most recent and questionable ones) that are not in glaring contrast with the specific quality of the space whose restitution is aimed at, that is to say with its characteristic unity. The spatial unity of cavea and stage equipment, the chief feature by which the Roman theatre may be identified on the plane of its architecture, consequently becomes the prior objective of the intervention hypothesized here.

This signifies that the project of restoration and historical restitution cannot help turning into, to all intents and purposes, the design of a Roman theatre (a theatre «in the style of the ancient Romans»). In other words, the design of a partially new theatre building founded both on the existing structure (literally, materially) and on an established building pattern whose condition of necessity (utility and function in the broadest sense) is wholly contained within its fixed form. A project, that is, which intends to take from the ancient structure every trace, every hint, every working indication, but above all its general lesson of architecture, seeking to carry it on with consistency.

In such a way not only its proportions, relationships etc. will derive from observation and study of the ancient structure, but also those choices of technique, function, construction, decoration etc. that become necessary over the course of the works, will have in the ancient structure and in their relation to it their sole raison d’etre as architecture.

All that has been said so far naturally implies recognition of the fact that the Roman theatre is also something that goes beyond its mere form, that it is also a definite type of theatre. A type of theatre, i. e. an idea of theatre, surely still very conscious of its ritual and evocative purpose etc. of its being a collective moment par excellence, like all ancient theatres, but also increasingly open to change, ever more fertile and spectacular, through the extension of themes (the closer and closer relationship with everyday life), the development of technical, scenic and interpretative possibilities (from script to rough draft, to improvisation, and so on), a theatre already very near to that concept of theatre which belongs to our more immediate past.

This is how the practical aim of our working hypothesis should be understood, as that of constructing at the same time a modern and perfectly functioning theatrical space.