The late 1960s were the time for social and intellectual conflicts, in Italy and around the world, for immersion countered by escapism, more rarely for the exaltation of bewilderment. In 1968, Sottsass made an encounter, with a woman who gave him a sense of a life independent of the social and intellectual conformism of an era; an encounter from which he would not only find a new perspective for a series of jewels and for the category of ornament to which they belong, but also a plunge into his questions embracing the feminine, from the figure of Fernanda Pivano – his wife, “la Nanda” who pervades the text – to the nomadic figures who live “far out”, distant from all usual categorizations and physical spaces: figures who would have the last word. Sottsass’s photos and text would later appear in July of that year on Domus, issue 464.

The ornaments of the sun nomads are a thousand times better

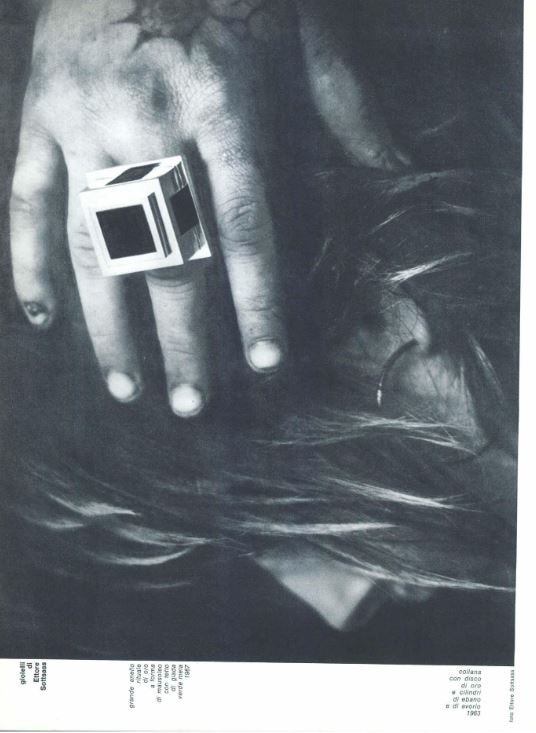

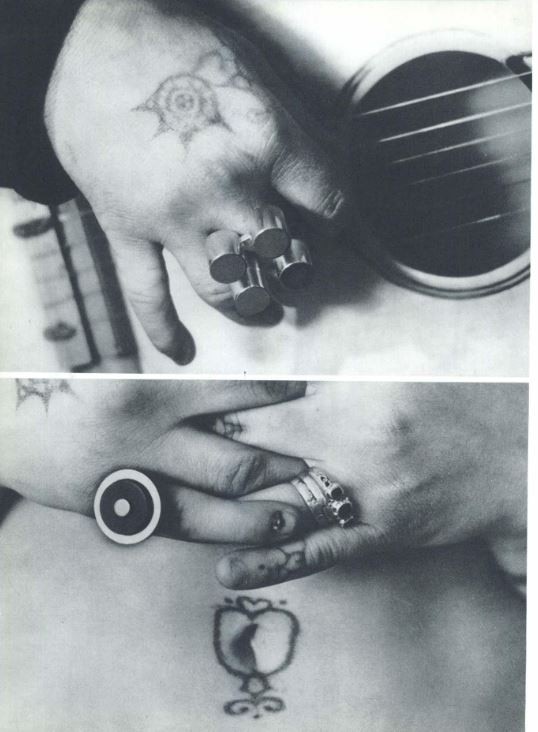

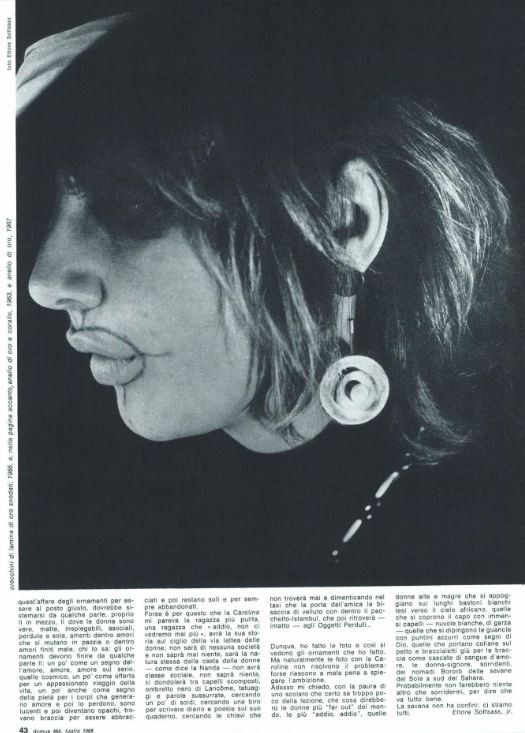

Some of these jewelries, of these ornaments, are from 1963 (when I did the exhibition with Nanda’s presentation) and some are recent.

Even the old ones had never been published, maybe because it was too complicated to photograph them and no one knew how to do it, or maybe because I was always waiting to be able to do a big series of ornaments someday, and that day instead had never come: who knew if it would.

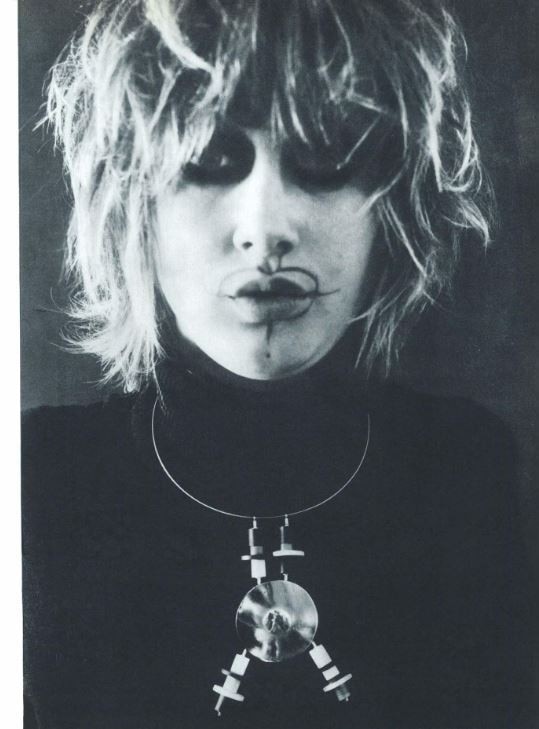

Instead, the other day, along came Caroline (with her friend Clara), a girl from New Zealand, walking on cowboy heeled shoes as if the floor had been the deck of a ship gone mad, and with real tattoos, forever indelible, on her forehead, around her mouth, on the hands and around the pink lips of the left breast, with hair like gypsies and eyes painted black as in oriental stories or stories of infernal witches, who knows; and it seemed to me that she was just right for wearing my out-of-place ornaments: a “far out” girl who had cut ties for good with general respectability, with class division and prêt à porter, with the talk, the party and the commitment, a girl who had gone into orbit and, goodbye, we’ll never see each other again.

So I took the photographs, which may have come out badly but anyways wanted to explain how this ornament business of mine would like to go much farther than it seems; it would like to fly lightly above the silent, grim, rabid proletarian competition, above the small, petulant, sour bourgeois competition, above the big, skinny, scraggly competition of the rich, and even above the presumptuous, cowardly, poisonous competition of the intellectuals, to rest on those cushions where femininity is inexplicable and unexplained, where women have a way of doing and being that you just can’t understand in whys and hows: there where one does not understand, to tell the truth, what is inside the shining flesh of girls from all places in the world, when they begin, each on her own, carrying around heavy hair, thin little arms and moist eyes, the story of the world from the very first beginning. From the tree and the snake and the apple, which is then made of bits of cloth, little buttons, little slides, flowers, little laughs, little ribbons, little dots and drawn stripes, little red nails and little teeth.

Even one cannot understand what it is like for the illiterate servant girls of Tibet, the best at making tantric love, and one cannot understand the celestial fairies with satin slippers appearing among the lichens of the dolomite forests, and even one cannot understand the half-naked blue girls stuck on the window of the truck drivers’ cab, and even less can one understand the witches with shawls and long skirts, nor the ghostly geisha silver pendants, nor can one explain the sick women who inhabited harems, feeding on boiling barracks-fashioned soups; and the Supersex girls, Sexibell (the mother) and Sexiboy (the child) with their double garters?

Hard to understand women, if one jumps over the glacial patterns of competitions; and these ornaments in any case, to be in the right place, should settle somewhere, right there in the middle, where women are real, crazy, unaccountable, asocial, lost and lonely, lovers within loves that turn to madness or within loves gone wrong, who knows: the ornaments must end up somewhere there; partly as a sign of love, love, love for real, the cosmic kind, partly as an offering for a passionate journey of life, partly also as a sign of pity for bodies that generate love and then lose it, shine to then become dull, find arms to be embraced to then remain alone and forever abandoned.

Perhaps that is why Caroline seemed to me the cleanest girl, a “goodbye, we will never see each other again” girl, having her story at the borders of the milky way of women; she will belong to no society and will never know anything, she will be the very nature of the caste of women – as Nanda says – she will have no social class, she will know nothing, she will be swinging between disheveled hair, black Lancôme eye shadow, tattoos and whispered words, looking for some money, looking for a ballpoint pen to write diary and poems in her notebook, looking for the keys she will never find, and forgetting in the cab taking her to her friend’s the velvet saddlebag with the lstanbul package inside, which she will later find again – intact – at the Lost and Found. ..

So, I took the pictures and so you can see the ornaments I made. But of course, photos with Caroline don’t solve the problem: perhaps they can barely explain the ambition.

Now I wonder, with the fear of a schoolboy who certainly knows too little about the lesson, what the most “far out” women in the world would say, the most “farewell, farewell” those tall, skinny women who lean on long white sticks stretched toward the African sky, those who cover their heads with immense hats – white clouds, of gauze – the ones who paint their cheeks with blue dots like signs from God, the ones who wear necklaces on their chests and bracelets down their arms like cascades of love blood, the smiling Bororó nomad lady-women from the Sun savannas south of the Sahara.

They would probably do nothing but smile at me, to say it’s all right.

The savannah has no boundaries: we’re all in.